Professor, Texas Tech University and CEO, ATMOS Research

In this issue’s Q&A, Texas+Water Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Todd Votteler, interviews Dr. Katharine Hayhoe, Professor in the Public Administration program at Texas Tech University and Director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech, part of the Department of the Interior’s South-Central Climate Science Center. Dr. Hayhoe’s research focuses on developing and applying high-resolution climate projections to evaluate the future impacts of climate change on human society and the natural environment.

In this issue’s Q&A, Texas+Water Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Todd Votteler, interviews Dr. Katharine Hayhoe, Professor in the Public Administration program at Texas Tech University and Director of the Climate Science Center at Texas Tech, part of the Department of the Interior’s South-Central Climate Science Center. Dr. Hayhoe’s research focuses on developing and applying high-resolution climate projections to evaluate the future impacts of climate change on human society and the natural environment.

She has published over 125 peer-reviewed abstracts and publications and served as lead author on key reports for the U.S. Global Change Research Program and the National Academy of Sciences, including the Second, Third and Fourth U.S. National Climate Assessments and the 2017 Climate Science Special Report.

Texas’ climate is naturally extreme. Why does climate change matter to our state?

If these risks are natural, then why do we care about climate change? It’s because, when it comes to extreme weather, climate change is loading the dice against us. It’s taking our naturally-occurring risks and making them stronger, or more frequent, or longer – or sometimes, all three. As average temperature increases, extreme heat becomes more frequent and heat waves, more severe. The scorching summer of 2011, which set record numbers of days per year over 100°F, could be the average summer for our state by mid-century, if carbon emissions continue at current rates.

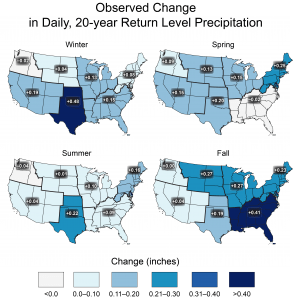

Heavy rainfall events are also getting worse. Warmer air holds more water vapour and warmer temperatures increase evaporation – so when a storm comes along, there’s more water vapour for it to sweep up and dump on us today than there would have been 50 or 100 years ago. Heavy rain events have increased across the entire U.S., and in Texas it’s the eastern half of the state that has borne the brunt of them.

It’s not just about heavy rain, though – our droughts are worsening, too. Our own research has shown that summer droughts over the south-central U.S. will get stronger and occur more frequently in a warmer world. The semi-permanent high pressure system that extends across our region in summer, suppressing convective activity and directing storms away from Texas, will be strengthened and prolonged by ocean temperature increases in the Gulf of Mexico: and the warmer it gets, the worse the effect will be.

The transition from drought to flood in Texas is already so fast, it practically gives us whiplash. In August 2018, nearly 80 percent of the state was in drought conditions; then came the wettest fall on record. And as the world warms, amplifying our droughts and heavy rain events, this whiplash effect will just get worse.

Our coasts are at risk, too. Despite the record-setting season of 2017, hurricanes are not getting more frequent, long-term. But the storms we’re seeing are intensifying faster, growing stronger, moving more slowly, and dumping a lot more rain. It’s estimated that almost 40 percent of the rain that fell during Hurricane Harvey would not have fallen if the same storm had occurred a hundred years ago. Sea level rise is threatening many coastal communities, and warming ocean waters are affecting our fisheries and our ecosystems.

We care about a changing climate because it affects us, in the places where we live.

Every year our population grows and our infrastructure ages, making us more vulnerable to these changes. What can we do to prepare?

As John Holdren, the science advisor to President Obama, once said: “We basically have three choices: mitigation, adaptation, and suffering. We’re going to do some of each; the question is what the mix is going to be. The more mitigation we do, the less adaptation will be required, and the less suffering there will be.”

In terms of mitigation, Texas is the number one producer of carbon emissions in the United States. If Texas were its own country, it would be the seventh largest emitter in the world. But Texas also understands energy better than any other state. And when it comes to the clean energy of the future, which is what we need to cut our carbon emissions, we’re well on our way.

In 2016, we generated 12 percent of our electricity from wind; in 2017, 16 percent and another 1-2 percent from solar. Wind energy already generates over 25,000 jobs across Texas and, per kilowatt-hour, it’s cheaper than natural gas in many of our markets. New wind and solar farms are popping up everywhere, even up here in West Texas. Climate change mitigation  isn’t just an economic challenge: it represents an economic opportunity to wean ourselves off our old and dirty ways of getting energy and replace those with the clean renewable energy sources we can grow right here at home. Yes, Texas is part of the problem – but Texas is also a big part of the solution.

isn’t just an economic challenge: it represents an economic opportunity to wean ourselves off our old and dirty ways of getting energy and replace those with the clean renewable energy sources we can grow right here at home. Yes, Texas is part of the problem – but Texas is also a big part of the solution.

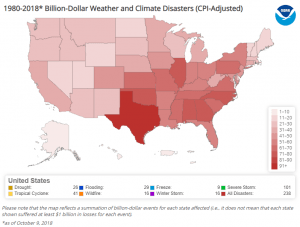

In terms of adaptation, we’re already the most vulnerable to weather and climate disasters; but that means we know what they look like, and how important it is to prepare. That’s why I work with organizations like Austin Water and the North Texas Municipal Water District and engineering firms like Freese and Nichols; and that’s why I talk to organizations like the Texas Corn Producers and the Hill Country Alliance and the city of San Antonio. Through my research, I develop and test high-resolution climate projections: information on how temperature, rainfall, humidity, and other important aspects of climate will change as the world warms by one, or two, or three degrees. And I help people figure out how to use this information to plan for future water availability, energy demand, crop yields, and more. If we know how the risks are changing, we can prepare for them.

Why are mitigation and adaptation so important? Mitigation helps us reduce the impacts we can’t prepare for; adaptation helps us prepare for those we can. And if we’re not prepared, we’ll suffer. Climate change affects farmers and producers, water managers, cities and towns, the energy industry, the economy, and most of all, those who are already up against the wall. As the U.S. military puts it, climate change is a threat multiplier. It takes the problems we already face today – aging infrastructure, pollution, even poverty and hunger, right here in Texas, and around the world – and makes them worse. That’s why we have to fix it, now.

Speaking of the world, what do you think is the most important finding in the new 1.5oC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report?

The IPCC assessment reports describe how the climate will change, and how these changes will affect human society and the natural environment around the world, under different scenarios.

These scenarios range from a future where the world continues to depend on fossil fuels to one where we wean ourselves off carbon-based fuels before the end of the century.

I use these scenarios in my research, but here’s the problem: international targets aren’t tagged to specific scenarios. The Paris Agreement is expressed in terms of global temperature change, which doesn’t depend on a pathway or scenario but simply on cumulative carbon emissions since the beginning of the industrial era. Specifically, its goal is to hold “the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.”

Going into Paris, we already had a good idea of how a 2°C or 3.5°F warming would affect crop yields, water resources, ecosystems and more. Scientists and policy makers had been studying this for more than a decade. But no one had spent a lot of time studying how a 1.5°C warming would affect us; and, even more importantly, no one really knew how much we’d save by limiting global warming by one extra half degree.

That’s why the most important result of the new IPCC report is that it identifies specific aspects of climate change – including extreme temperatures and heat waves, heavy rain events, and droughts, all of which matter to Texas – that increase with global mean temperature. By doing so, it quantifies the impact of our choices today on our future. We still haven’t exceeded the carbon budget that would make a 1.5°C or 2°C warming inevitable, so we can still choose: and now, with the information provided by this report, we can do so with a better understanding of what these choices will mean for our future.

Given that the world appears to be on track to reach CO2 levels that constitute the highest scenario and the United States has withdrawn from the Paris Agreement, do you ever get discouraged in your work?

Yes! Every time a new study comes out, these days, it seems that some aspect of climate is changing faster or to a greater extent than we thought. Sea level is rising twice as fast as we previously thought. The ocean is storing even more heat. Storms and hurricanes are being super-charged by a warming planet far beyond the 6-7 percent per degree C of warming that basic physics predicted. It’s hard not to be discouraged, as each new study paints a picture that is grimmer than the last.

And the politics is even worse. In November 2017, we released the first volume of the Fourth US National Climate Assessment. It concluded that, “global climate continues to change rapidly compared to the pace of the natural variations in climate that have occurred throughout Earth’s history,” and “human influence has been the dominant cause of the observed warming; there are no convincing alternative explanations supported by the extent of the observational evidence.” Yet the White House’s official response was, “the climate has changed and is always changing.” And then a year later, we heard that they were using the projections we generated for the higher scenario, showing how much the U.S. would warm if we continued to depend on coal, oil, and gas, to argue that there was no point continuing with fuel efficiency standards because it’s just going to warm by 7°F anyways.

In November 2018, we released the second volume of the assessment, which describes in detail how climate change is already affecting every region and nearly every sector of the U.S., from our health and our economy to infrastructure and water resources. Again, the administration’s response was off base: they claimed the results were only based on a “most-extreme” scenario when in fact much of it was based on observational data. When discussion future impacts, we considered a broad range of scenarios, from a very low scenario where emissions go negative before end of century to a higher scenario where emissions continue to grow, although with substantial technological development. And political pundits abounded, claiming that we climate scientists were “driven by money” in writing this report; when in fact we were paid absolutely nothing for our effort.

Given the nature of public discourse over climate change, it’s no surprise that, “what gives you hope?” is one of the most frequent questions I get. And I do have hope: but it doesn’t come from the science, and it certainly doesn’t come from the politics. My hope comes from looking at what people – countries and states, organizations and businesses, individual people and even kids – are doing. Scotland is already generating nearly 70 percent of its electricity from wind, sun, and tides. British Columbia has had a price on carbon for over 10 years; during that time, they used the revenues to reduce personal income tax to the lowest rates in Canada and grew their economy. Walmart is the largest company in the world; they’re planning to generate half their energy from clean sources by 2025 and they’re leading a global effort to remove a gigaton of carbon – that’s one tenth of all human emissions – from the global supply chain.

ClimeWorks, a Swiss company, has figured out how to suck carbon dioxide out of the air and turn it into fuel. It isn’t cheap yet, but it’s possible! Sara Volz was just a 17-year-old from Colorado Springs when she won Intel’s big science fair for figuring out a more efficient way to turn algae into biofuel: with an experiment she built in her bedroom. And biofuel is already being used today, on some United flights from LA and they don’t even require any modifications to the engines. Indiana is one of the most coal-intensive states in the country; but one of its biggest electricity producers just announced they’ll be phasing out coal and replacing it with renewables simply because it will save their consumers 4 billion dollars over the next three decades. And of course here in Texas we have Fort Hood, the biggest army base in the U.S., which two years ago purchased a contract for wind and solar energy because they would a lot of money – starting with 1.5 million taxpayer dollars the first year – compared to natural gas.

There’s plenty of hope, all around us. We just have to look for it.

How do you strike the balance between being a scientist and an advocate?

As climate scientists, I believe our work can be policy-relevant, but not policy-prescriptive. Science can tell us what the outcome of our choices will be, but it can’t say for sure what’s the best thing to do. That’s because solutions don’t just depend on the science: they also depend on our values. Do we prefer a free or a regulated market? Investing in efficiency and conservation or wind and solar? Helping other people or looking out for yourself?

That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t talk about solutions: in fact, talking solutions is one of the most important things we can do! We don’t have to tell people what do to: that’s what our individual choices, our city and state governments, and our political systems are for. But we can and should lay out the range of choices available, so people know what the options look like.

Imagine you’re running a low-grade fever, one that starts to increase gradually, week after week. You go to the doctor, and the doctor runs a massive battery of tests. They consult with all the top experts in the world, and finally come to a conclusion: it’s your lifestyle that is causing the fever, and if you don’t change your ways, the results will be serious and even potentially dangerous. So you say to the doctor, “what should I do about this?” and the doctor leans back in their chair, folds their hands, and says, “don’t ask me!”

As scientists, I believe that if we’re going to tell people we have a problem, then we also need to educate ourselves on possible solutions: solutions that appeal to all kinds of people, that encompass a very broad range of political values. The Niskanen Center offers Libertarian approaches to climate policy; RepublicEn, which bills itself as the “eco-right,” develops free market solutions; the Climate Solutions Caucus proposes bipartisan solutions; the EPA works on regulatory approaches. Which of these policies is the right one? I’d say, whichever one people agree that they like best!

Personally, I’m in favour of solutions that reduce our carbon emissions and help people: like the solar panel manufacturing company in San Antonio that took in, retrained, and hired oil patch workers who’d lost their jobs; or companies and non-profits investing in pay-as-you-go solar that is electrifying sub-Saharan Africa, where hundreds of millions of people in poverty have no access to energy of any kind. But, as a scientist, I’m not advocating for any specific solution. Like a physician, I’m advocating on behalf of the human race. The reason I care about a changing climate is because it disproportionately affects the poorest and most vulnerable among us. That’s why I care, and that’s why I know we need to act.

When you began your research years ago did you ever think it might result in you becoming an internationally known figure?

Never! My sole goal as a graduate student entering this field was to maybe one day become a chapter lead author for an IPCC assessment report. Fast forward twenty years, and I’ve never been a lead IPCC author: but I’ve talked climate and religion with Gloria Steinem, participated in an Emmy award-winning documentary, given TED talks, visited the polar bears in the Arctic with the scientists who study them, headlined the South by South Lawn festival with President Obama and Leonardo DiCaprio, spoken at the Nobel Peace Prize Forum, and more.

Back in 2014, when I received the email notifying me I’d made the TIME 100 list of the most influential people in the world, I thought it was spam – you know, the kind where they say “congratulations, you’ve made the who’s who list, now send us a check for $500 to receive your fantastic certificate!” So I deleted the email and didn’t think twice about it.

A week later, I got another email. This one was a bit different. “Are you coming to the gala dinner?” it began, “We really need a head count.” That, I didn’t expect – so just in case it might be real, I forwarded it to our university’s communications office. They called back almost immediately. “Are you sitting down?” they asked. “It’s real, and you’re going!”

I’m constantly surprised and enormously grateful for these honours. What encourages me the most, though, is when just one person sincerely shares how they’d never cared about climate change or thought it was real: but now, because of something I said, they’ve changed their mind. That’s what makes it all worthwhile.