In this issue’s Q&A, Texas+Water Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Todd Votteler, interviews Ayanna Jolivet Mccloud, Executive Director of Bayou City Waterkeeper (BCWK).

Mccloud supports community efforts to improve water quality, wetland protection, and flood mitigation/recovery at BCWK. She has led programs and mobilized resources at environmental and cultural institutions for over 20 years before joining BCWK in 2021. A native Houstonian, she is committed to developing new frameworks for advocating for water, natural resources, and people in greater Houston that center on community-powered policy, ecological imagination, and equity.

Please tell us about BCWK’s work, history, and impacts.

Using science, law, and education, BCWK works with communities across the 4,000 square miles of the Lower Galveston Bay watershed, which encompasses greater Houston, to protect water quality, preserve and restore wetlands, and support equitable flood resiliency and water infrastructure.

The size of our watershed, the complexity of our region, and the urgency of climate change require a new approach to solving how we live with and advocate for water. BCWK works at the unique intersection of conservation and environmental justice, working across disciplines using data-to-action science frameworks alongside law and education and collaborating with community partners. We strengthen front-line community voice and actions and shift culture change in policy through litigation, legal and policy education, community environmental science, research, mapping, and design.

For 21 years, BCWK has primarily focused on Clean Water Act compliance. The Clean Water Act provides the single most crucial tool that community members in the region have to ensure that negative water quality impacts are minimized and viable mitigation for coastal wetland destruction is implemented.

As our region has suffered increased storms with Hurricane Harvey, our work has expanded to focus on resiliency efforts around flood mitigation and water infrastructure. BCWK serves a unique role within our region in post-Harvey recovery as we provide technical, policy, and legal assistance to communities and organizations throughout the Lower Galveston Bay watershed.

We are currently in a period when the approach to flooding in Texas as well as across the United States is changing. What changes do you see happening locally, and what role does BCWK play in those changes within the Lower Galveston Bay watershed?

Watershed resiliency efforts in a region as diverse as greater Houston must center people, including inequities and environmental justice, alongside conservation of our natural resources.

In Houston, Hurricane Harvey was the catalyst to apply new ways of working with water.

The long-term impacts of increasing floods and poor water quality disproportionately affect low-income communities of color. Each major storm has brought opportunities to undo much of this harm and make better decisions and investments in our future. Communities hit hardest by Harvey and with a lower means to recover are those with a high concentration of poverty, those with a large percentage of immigrant populations, those along the industrial ship channel, and those in the unincorporated areas of Harris County that fall outside the jurisdiction of the city of Houston.

Post-Harvey, new organizations have launched, including the Community Flood Resilience Task Force; the Coalition for Environment, Equity, and Resilience, which BCWK is a member of; and grassroots organizations such as West Street Recovery, Northeast Action Collective, and the HOME Coalition. Additionally, new funding has been allocated for flooding through Harris County’s 2018 $2.5 billion flood bond, which is slowly moving and still $1.4 billion short. In the last five years, we have learned that flooding is the point of entry to a much larger systemic issue. How we work has to be collaborative across industries and disciplines, and it has to be community-powered. Flooding is not just about water. It concerns drainage, sewer overflows, weatherization, nature-based protections provided by wetlands and other green infrastructure, nuisance and large-scale infrastructure, and climate change.

BCWK’s role is as a resource, facilitator, watchdog, and think-tank/action-tank for both front-line communities in urban areas and coastal communities. How can we work in new ways to address flooding in our region? How can we offer data-to-action frameworks through mapping and toolkits? BCWK has emerged as unique in this region for its ability to use selective, strategic litigation addressing stressors in our watershed by targeting local sources of pollution and flooding.

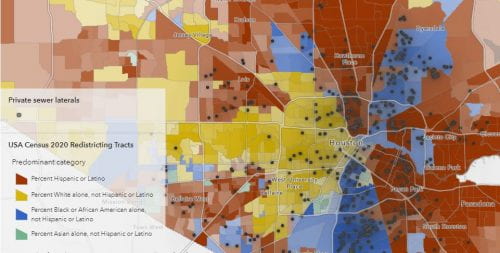

BCWK supports nuanced, community-powered visions for water infrastructure, including flood and storm surge infrastructure, and building nature-based resilience to address flooding and climate inequities across the Lower Galveston Bay watershed. Within Harris County, our approach centers on historically underserved communities most affected by flooding during Harvey and other major storms, pollution, and other climate impacts, such as the Fifth Ward, East End, Gulfton/Sharpstown, Third Ward, and Northeast Houston. These communities are predominantly Black and brown, low-income, urban neighborhoods disproportionately burdened by environmental harms and risks that impact their health. Along the coast, our work focuses on integrating nature-based solutions into coastal protection plans to support long-term resilience and preserve the natural systems that make our region special. Recently, we have co-hosted community forums critiquing the Ike Dike.

How do you work around water quality monitoring and clean water in your watershed?

Strategic use of the law allows BCWK to hold polluters and decision-makers accountable and protect the communities most affected by water pollution across the watershed. BCWK works toward cleaner water and environmental justice by strengthening compliance with the Clean Water Act, filling monitoring gaps across the watershed, and emphasizing equity and justice in decision-making processes.

Our watershed’s bayous, creeks, streams, and bays are listed as impaired. Major pollution sources include dysfunctional sanitary sewer and stormwater infrastructure, ineffectively regulated industrial pollution, improperly secured hazardous waste sites, and plastic pollution. Storms, growing in strength due to climate change, amplify the pollution’s impacts. Zip code largely determines the extent to which a community is affected by water pollution; low-income communities and communities of color generally bear an unfair share of this burden.

The Clean Water Act’s citizen suit provision authorizes people and organizations to sue to enforce violations, but water quality violations are under-enforced across our region, and permit processes and rulemakings move forward without meaningful input from people most affected by pollution within our watershed. Moreover, monitoring data across the watershed is incomplete, further undermining enforcement. While decision-makers increasingly accept that equity and environmental justice are important values, they have difficulty actively pursuing and integrating these values into processes and practices that have been in place for decades.

In 2018, BCWK uncovered a significant source of water pollution in the Lower Galveston Bay watershed — the city of Houston’s sewage treatment system. These violations were discovered after combing through five years of data submitted by the city of Houston to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality. We identified more than 13,000 illegal overflows from 2011 to 2017, representing more than 80 million gallons of sewage evading treatment, which had occurred across the city’s massive sanitary sewer system and had polluted our local bayous and creeks, as well as neighborhood parks and school playgrounds. This led us to serve the city of Houston with a notice of intent to sue under the Clean Water Act, which prompted the United States and the state of Texas to file an enforcement action two months later. Last year, these efforts culminated in a $2 billion consent decree, which will lead to significant infrastructure improvements across the city over the next 15 years.

Earlier this year, BCWK served the city of Baytown with a under the Clean Water Act. Similar to our legal action against the city of Houston, this notice targets problems with Baytown’s ailing sanitary sewer system. Our analysis identified more than 800 potential violations of the Clean Water Act sanitary sewer overflows — 882 overflows representing more than 21 million gallons of sewage leaving Baytown’s system without treatment from 2016 to 2021. Our analysis also concluded that the highest volume overflows had disproportionately impacted Hispanic/Latinx communities in Baytown. We asked for the court’s permission to intervene and help drive these legal violations toward a resolution that focuses on the communities most affected by sewage pollution in Baytown through a process that is transparent and accessible.

Prompted by our notice of intent to sue, the U.S. Department of Justice filed a lawsuit or enforcement action against the city of Baytown.

According to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, we have less than half of the wetlands in Texas that we had 200 years ago. How important are the remaining wetlands for the Houston region, Galveston Bay, and flood prevention, and how do we protect them?

Our region’s wetlands “once occupied almost a third of the landscape around Galveston Bay.” Today, they serve as “the headwaters for virtually all of the water bodies feeding into Galveston Bay.” They are a “critical part of the aquatic integrity of our regional bayous and bays” and serve a vital role in protecting local communities against floods. The value of wetlands’ stormwater detention services alone has been estimated at a minimum of $600 million for the greater Houston region. When wetlands’ other functions are added to this figure — protecting coastal areas and shorelines by weakening the force of storm surges, filtering pollutants carried by stormwater, replenishing groundwater supplies, reducing erosion, and providing habitat and places for people to rest and play — their estimated value leaps to the billions.

Over the last two decades, as storms have become more intense and more disastrous, our region has permanently lost hundreds of thousands of acres of wetlands to rapid commercial and residential development. This could have been avoided with better legal protections for wetlands. For decades, the only legal protections for wetlands in Texas have existed at the federal level through the Clean Water Act. But in our region in particular, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers — the federal agency with oversight of wetlands — has historically failed to enforce these protections outside of the 100-year floodplain. As a result, within our region, more than 80% of the wetlands that have been lost regionally to development in the past 25 years were outside the 100-year floodplain. Without any change in the Corps’ oversight within our region, we should expect to lose at least 100,000 more acres of wetlands to development in the next four decades — with grave consequences for local water quality, flood resilience, and environmental justice. Although flooding affects communities across our region, it compounds historic inequities and hits socially vulnerable communities hardest.

BCWK protects wetlands across the Lower Galveston Bay watershed through monitoring development in the region; ensuring that appropriate permits and mitigation are obtained for the destruction of wetlands; educating local, state, and federal agencies on integrating nature-based solutions into infrastructure planning; and conducting environmental outreach education. We are also launching “404 Wetland Permit” toolkits to guide communities concerned about wetland destruction through the process of demanding action and establishing an interactive map of critical wetlands in the regions.

We are fighting to expand and protect waters of the United States (WOTUS) by defending our wetlands at the U.S. Supreme Court with 40+ waterkeeper groups. We have collaboratively filed an amicus brief with the U.S. Supreme Court to defend the Clean Water Act from efforts to substantially narrow the definition of federally protected waters.

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provides $2.9 billion for Texas wastewater and drinking water infrastructure and lead service line removal. Additional funding will be available for other water infrastructure projects. What are the most important results you see the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act having within the Lower Galveston Bay watershed?

For more than 30 years, the state revolving funds (SRFs) have been the foundation of water infrastructure investments, providing low-cost financing for local projects across the United States. However, many vulnerable communities facing water challenges have not received their fair share of federal water infrastructure funding. Under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, also known as the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, states have a unique opportunity to correct this disparity.

The definition of disadvantaged communities is defined on a state level. Still, in the Lower Galveston Bay watershed, we can see some communities suffering historical impacts of disinvestment on the front lines of climate change and accelerated storms. Examples include threats to water security, such as unaffordable and rising water bills, contamination from lead and other harmful substances, more frequent flooding and sewer backups, and drainage issues, all of which are made worse by climate change. From a perspective of water infrastructure, these communities are experiencing water quality issues and more significant pollutants and health inequities.

These are moments in which we have to reimagine our framework and adapt to truly serve communities in need. The formula that state revolving funds have used since 1980s is dated, as is our aging water infrastructure. We must change the guardrails of how money is accessed and provide technical assistance to communities who have not typically accessed these funds. In addition to using technical assistance for engineering and design, these funds can also be used for community engagement. Additionally, we must envision a water workforce that is more diverse and reflective of changing demographics.

In greater Houston, the most diverse city and a coastal city facing future storms in a post-Harvey landscape, we need equitable implementation of water infrastructure funding.

Join Our Mailing List

Subscribe to Texas+Water and stay updated on the spectrum of Texas water issues including science, policy, and law.