SUMMARY:

-

Imelda was the fifth wettest tropical storm to hit the continental United States.

-

August was the second warmest on record and the warmest since 2011.

-

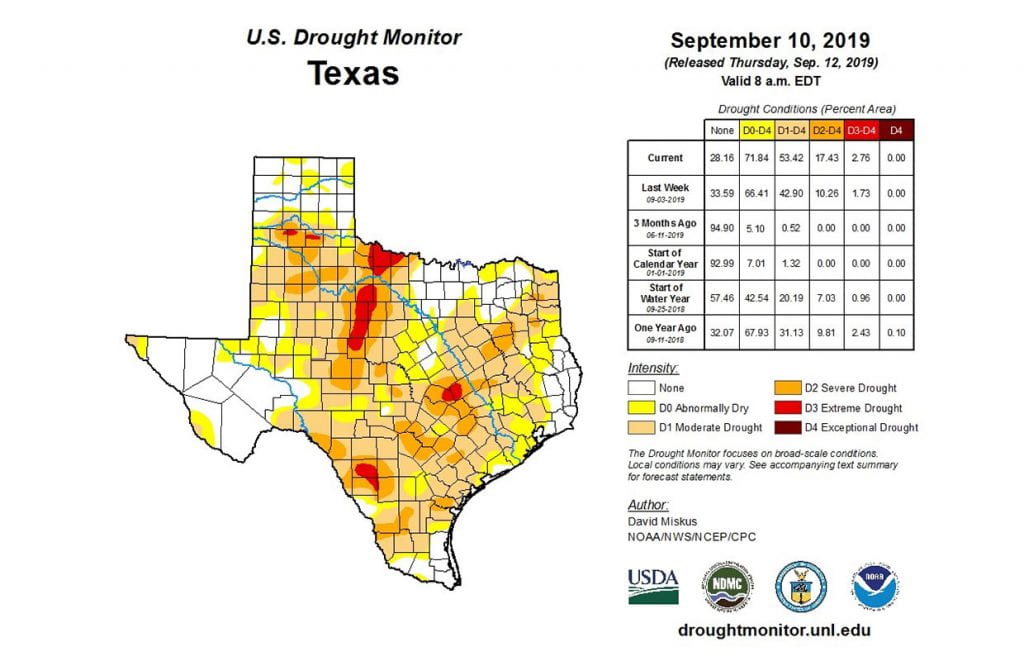

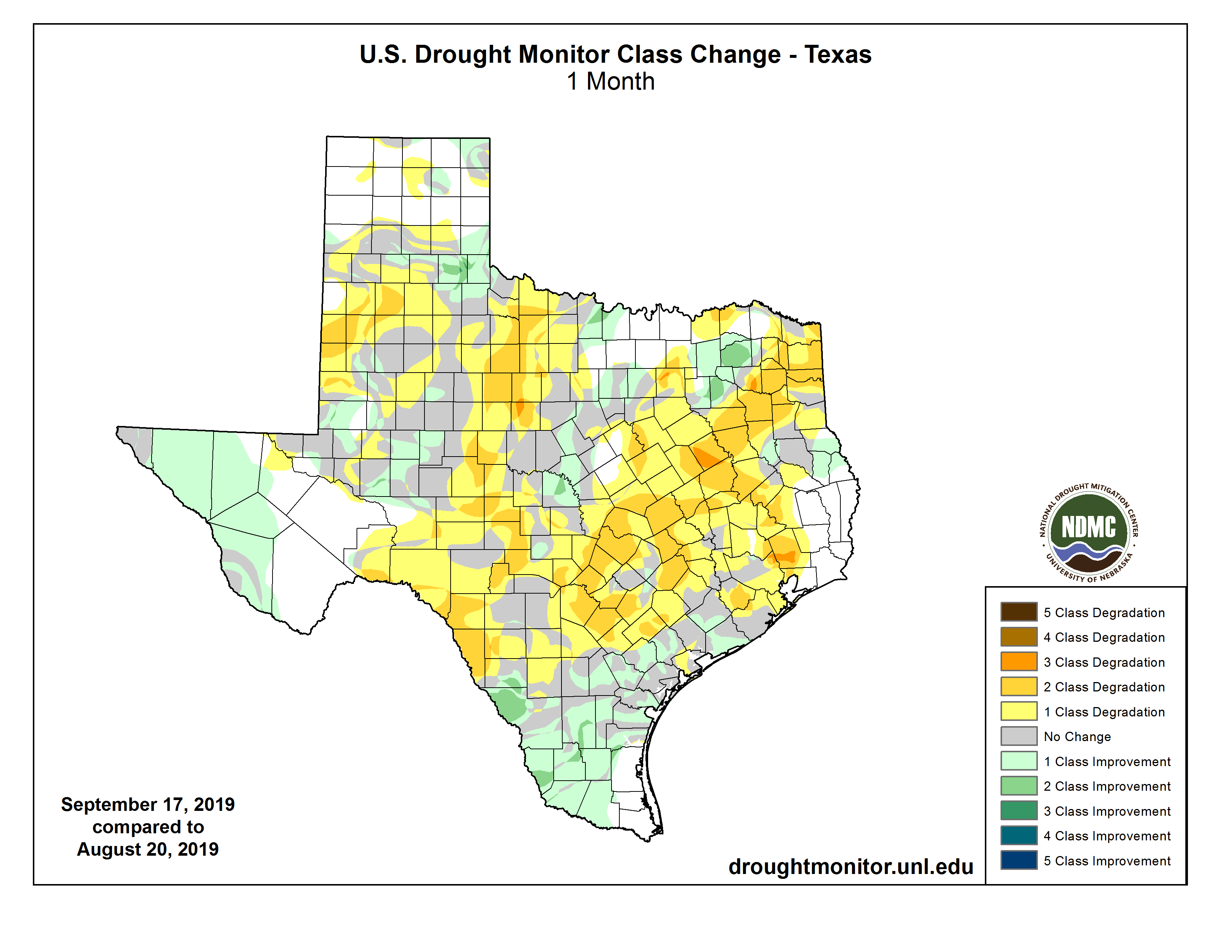

The state went from 22 percent in drought a month ago to 52 percent today with 72 percent of the state either in drought or abnormally dry.

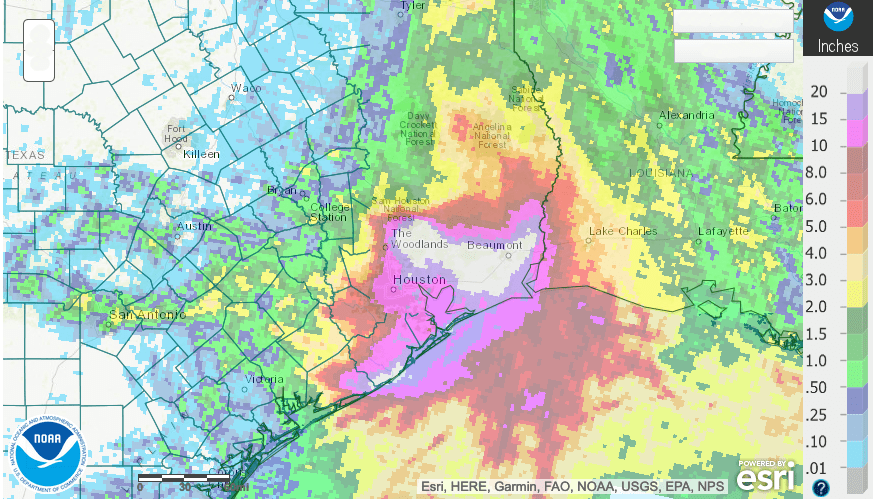

The big water news this month is Imelda, who started as an upper-level low on September 14 west of Florida. By September 17, the low had moved off the coast of Texas and turned into Tropical Depression 11. Later that same day, the depression strengthened into a tropical storm and then made landfall near Freeport where she quickly weakened back into a tropical depression. Despite not becoming a hurricane, Imelda’s slow progress in Texas allowed her to dump massive amounts of rain earning her the title of the fifth-wettest tropical cyclone to hit the continental United States with 43.25 inches of rainfall falling at a station in Jefferson County. Much of Imelda’s rainfall occurred from just west of Houston toward the Sabine River with a large blotch of 20 inches or more falling from east of The Woodlands over to Beaumont (Figure 1a).

Imelda’s impact was restricted to a small part of southeast Texas leaving the rest of the state in a continued state of drought. For example, it has been dry at my house in Austin, having only received an inch of rain since the end of June. Our rainwater tank, which I sized to provide outdoor water except during the worst of droughts, is the lowest it’s been since we installed it five years ago (Figure 1b). Part of this is the drought, part of this is unseasonably high temperatures and part of it is our cantaloupe, which has required daily watering rather than the usual twice-a-week-top-off our wicking gardens usually require (Figure 1b).

This past August was the second warmest in Texas with an average temperature of 86.0°F—4.1°F warmer than normal—and the warmest since August 2011 (which cooked us at 88.2°F). For high temperatures, this year’s August was the fourth warmest at 98.4°F, tying with 1899 and 1951. For rainfall, August 2019 clocked in as the 25th driest with 1.35 inches—the lowest since 2011—as compared with a normal of 2.31 inches.

The Climate Prediction Center released its update to the Atlantic hurricane season in early August projecting the potential for more activity than its earlier May update with 10 to 17 named storms, 5 to 9 hurricanes, 2 to 4 major storms and accumulated cyclone energy 85 to 165 percent of the median. September is the most active month of the hurricane season with September 10 being the peak day (Figure 1c).

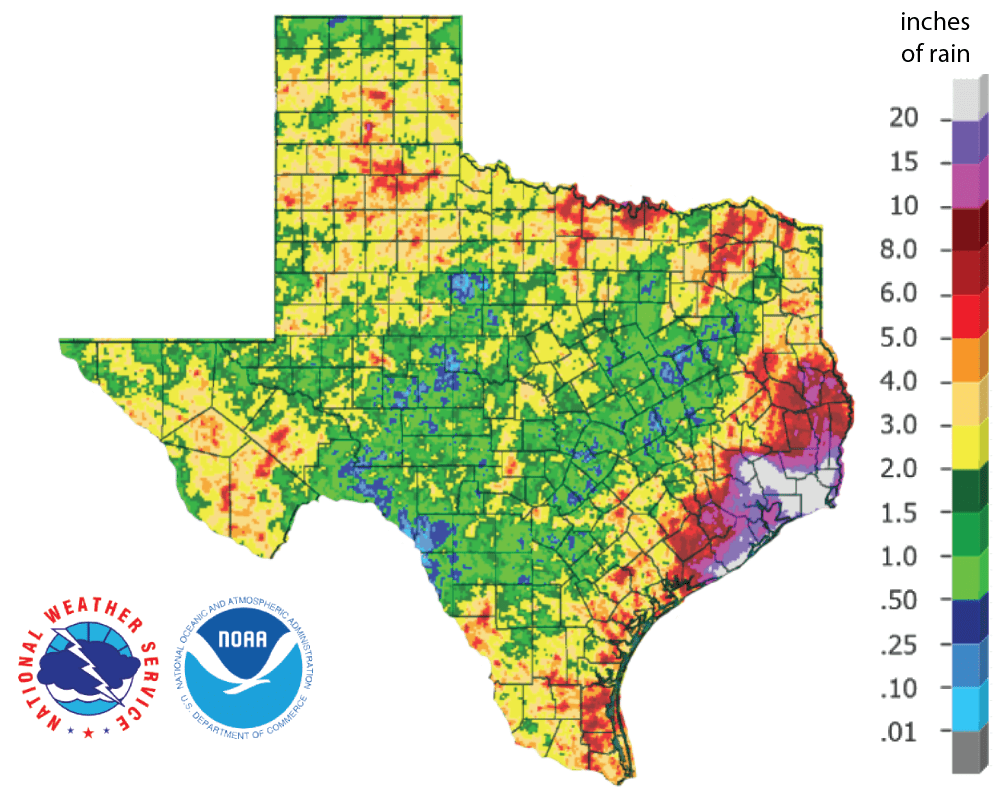

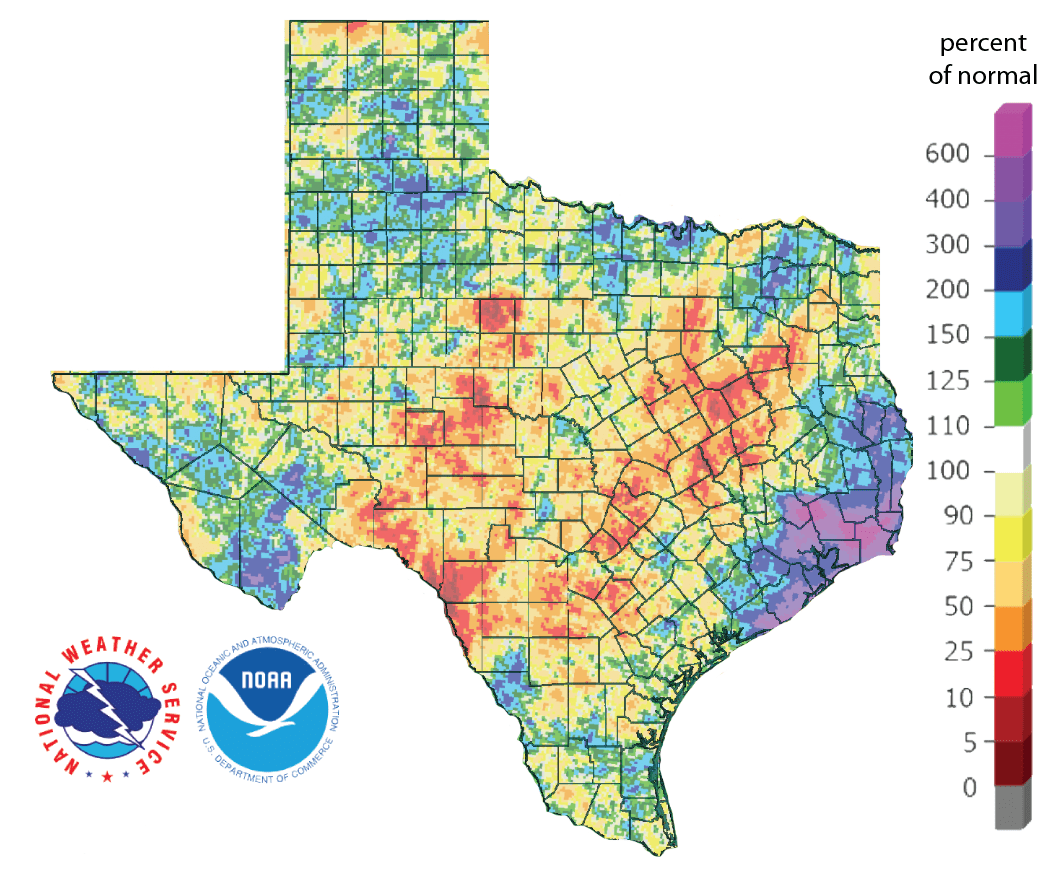

Besides the massive rainfall in southeast Texas, parts of the rest of the Gulf Coast, the Lower Rio Grande Valley, Big Bend and along the Red River received five inches or more of rainfall (Figure 2a). Much of the central part of the state has received less-than-normal amounts of rain with many areas receiving less than 25 percent of normal for this time of year (Figure 2b). Looking over the past 90 days, most of the state is still experiencing a rainfall deficit with the central part of the state receiving less than 50 percent of normal rainfall (Figure 2c). In general, percent-of-normal precipitation for the past 90 days correlates well with the Drought Monitor and can be used to discern areas going into (or out of) drought.

Drought increased in the state from 22 percent a month ago to 52 percent today with 72 percent of the state either in drought or abnormally dry (Figure 3a). Because there’s about a week delay between the drought monitor and recent events, the Houston area still appears under drought conditions (Figure 3a). Drought intensity has also generally worsened across the state with pockets of extreme drought in central, south-central and west Texas (Figure 3b).

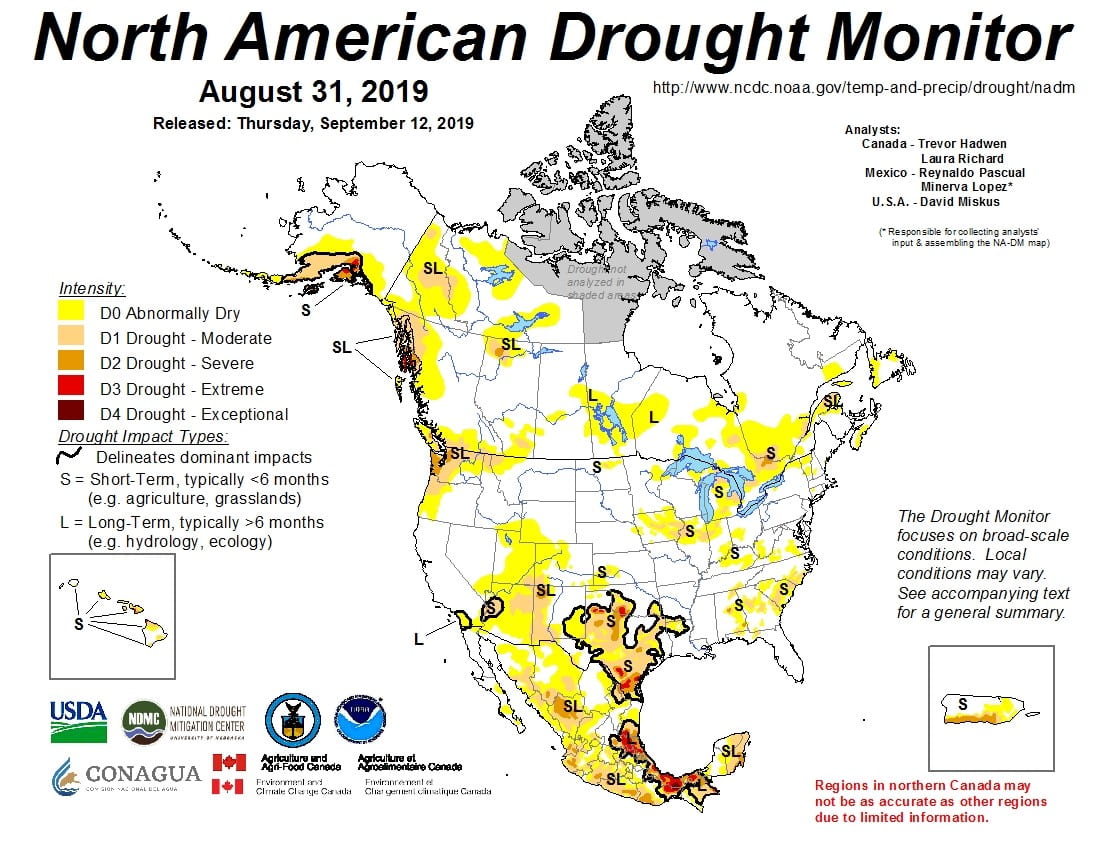

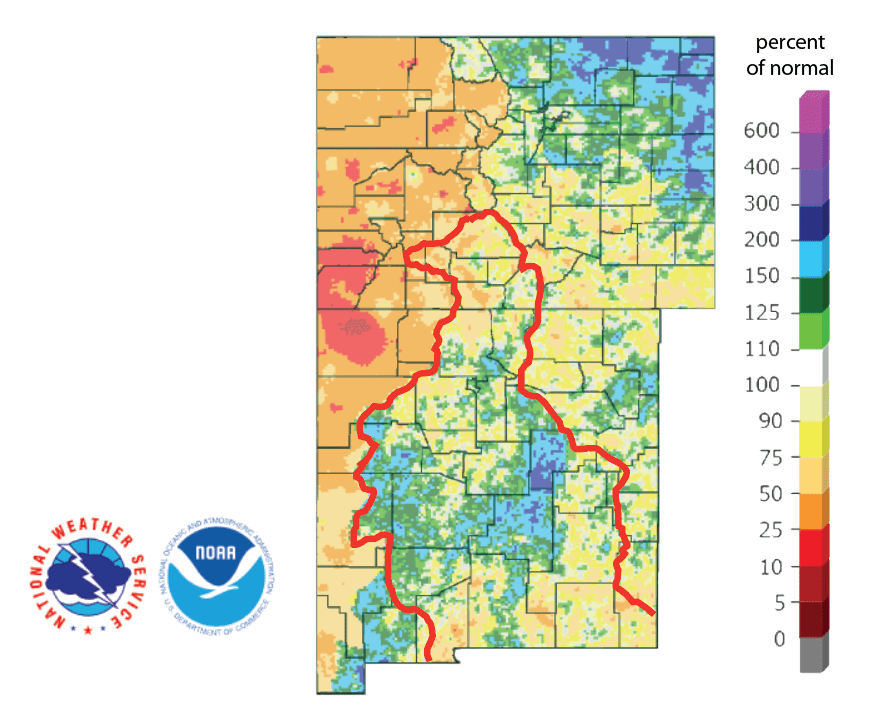

The North American Drought Monitor for the end of August continues shows a now-regional drought draped across Texas with short-term impacts to agriculture and grasslands in Texas (Figure 4a). Percent of normal precipitation in the Rio Grande watershed in Colorado, the primary source of water for Elephant Butte Reservoir, over the last 90 days shows less-than-normal rainfall; however, much of the basin in New Mexico has benefited from greater-than-normal rainfall (Figure 4b).

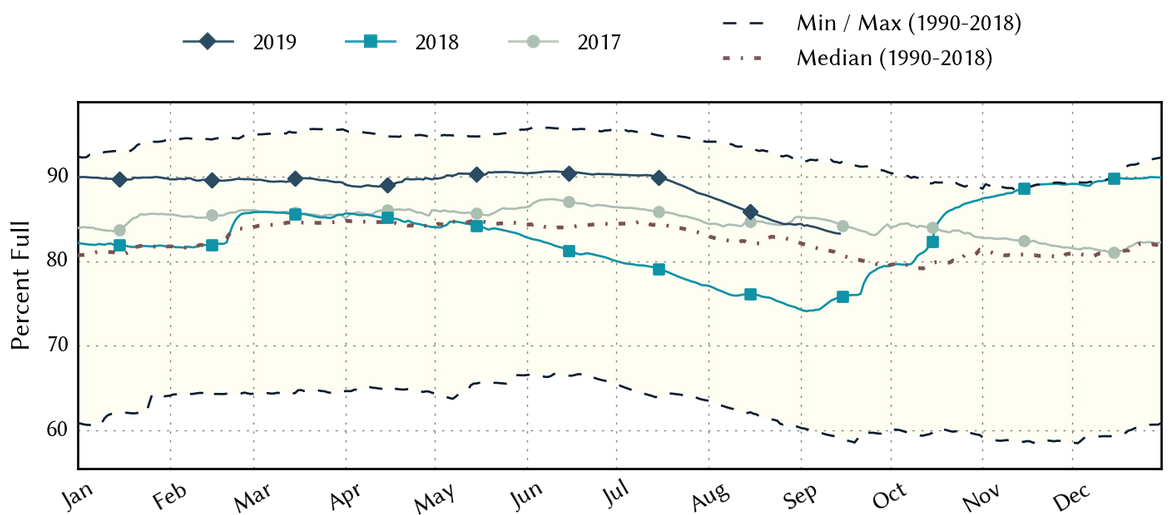

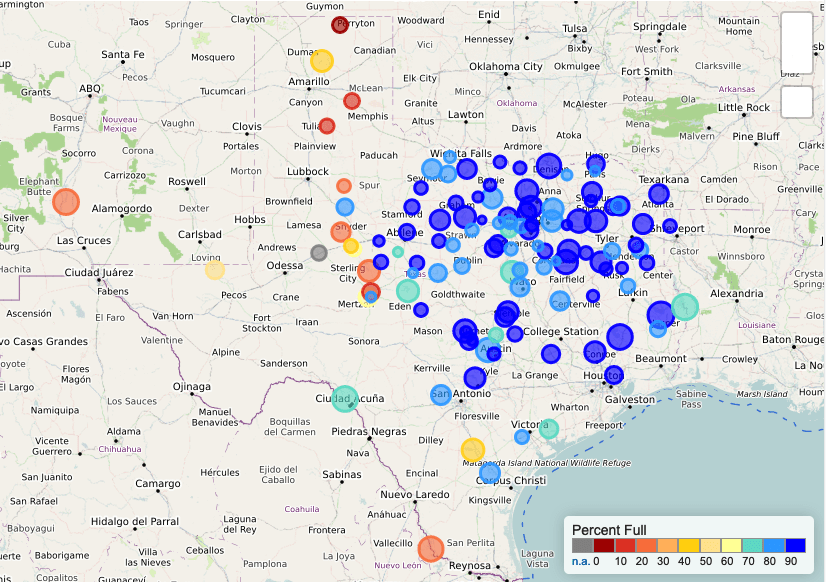

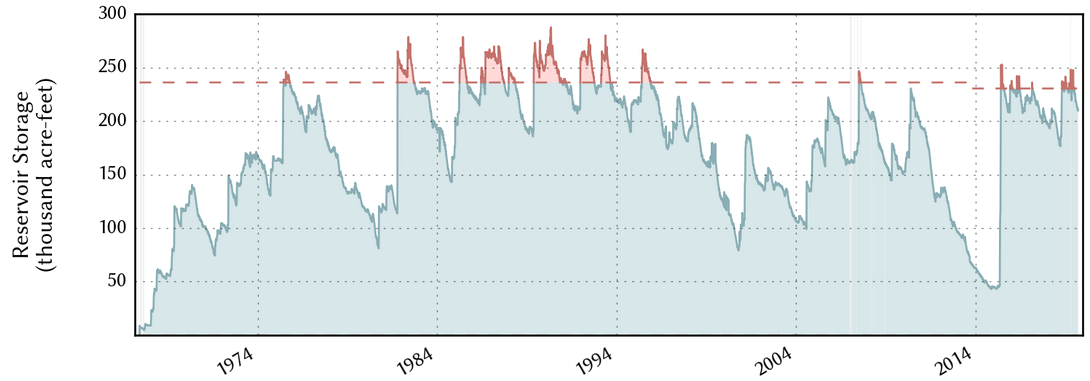

Statewide reservoir storage continued its decline that started in July to 83 percent full, still above the median storage since 1990 for this time of year (Figure 5a). Percent full status for individual reservoirs this month (Figure 5b) shows a number of reservoirs across the state declining in storage, although most of the reservoirs in the eastern half of the state remain at least 80 percent full.Despite the flash drought, most reservoirs are in good shape, such as Lake Arrowhead near Wichita Falls (Figure 5c).

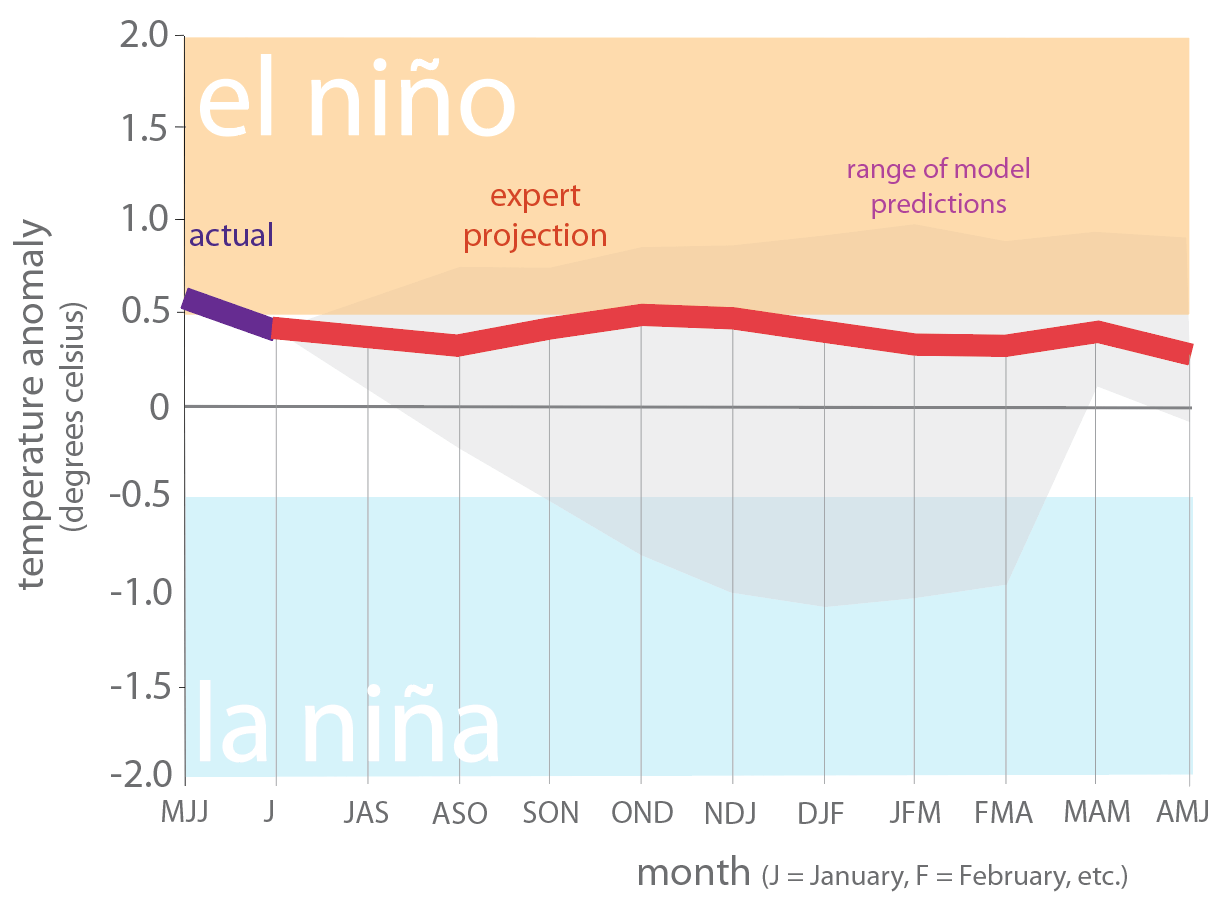

Over the past month we moved from an El Niño Advisory to “Not Active” due to the development of neutral (La Nada) conditions (Figure 6). Despite flirting with sea-surface temperatures consistent with El Niño conditions, the Climate Prediction Center predicts a 75 percent chance of neutral conditions continuing through the fall and a 55 to 60 percent chance of continuing through the spring.

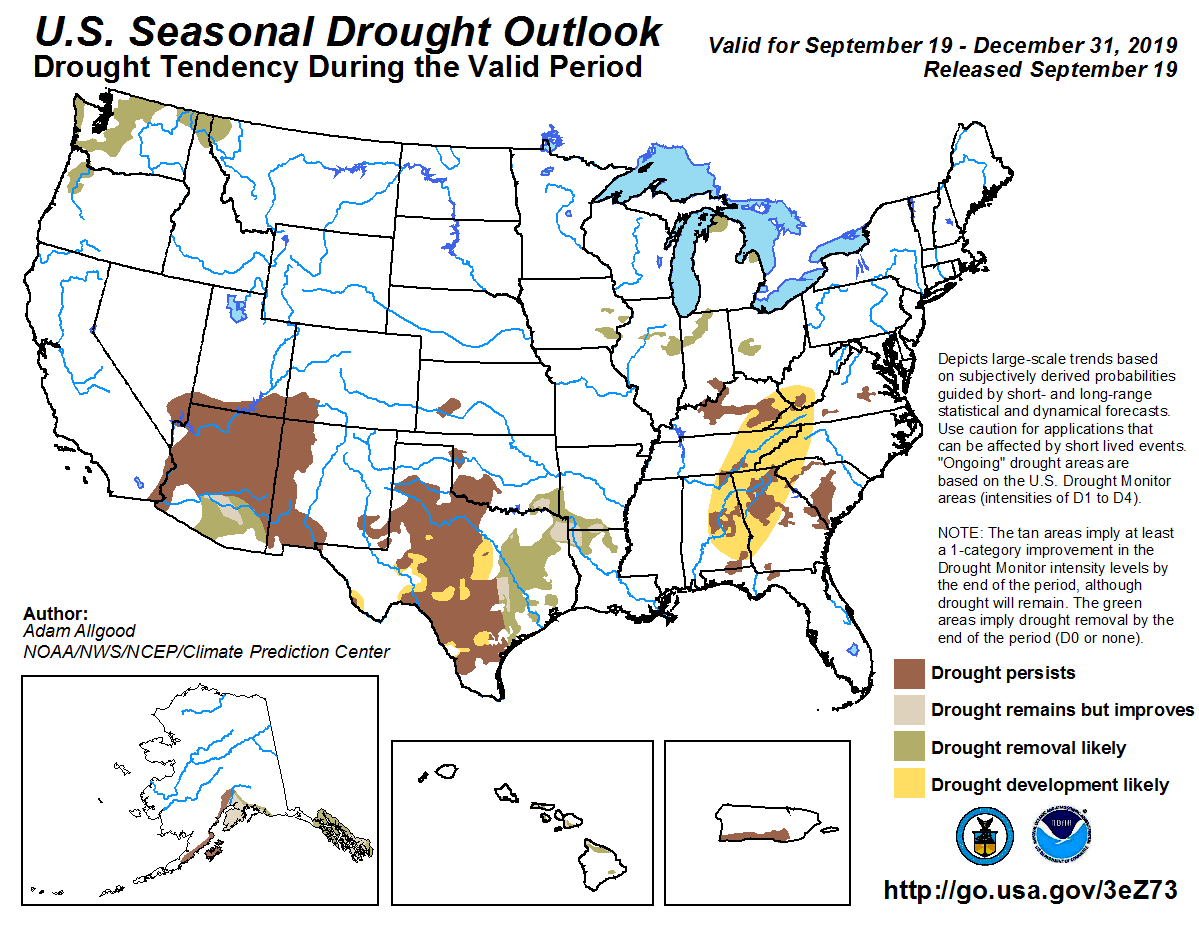

The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook through December 31, 2019 projects that current drought conditions will persist with drought conditions expanding in the central part of the state with drought conditions waning in the eastern part of the state (Figure 7).

Author

Robert Mace,

Robert Mace,

Interim Executive Director & Chief Water Policy Officer at The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment

Robert Mace is a Professor of Practice in the Department of Geography at Texas State University. Robert has over 30 years of experience in hydrology, hydrogeology, stakeholder processes, and water policy, mostly in Texas.