Mayor, the City of San Antonio

In this issue’s Q&A, Texas+Water Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Todd Votteler, interviews Ron Nirenberg, the Mayor of San Antonio, one of the nation’s fastest growing cities in the United States with the seventh largest population.

Nirenberg was raised in Austin and attended Trinity University in San Antonio. He is the son of an immigrant from Southeast Asia and the grandson of immigrants from Eastern Europe who passed through Ellis Island. Through his personal experiences, Mayor Nirenberg developed a core commitment to civic participation and the universal values of liberty, justice and equal opportunity for every person.

Nirenberg was first elected to represent District 8 on the San Antonio City Council in 2013. During his two terms, he championed smart city and regional planning, inclusive economic development, environmental stewardship, fiscal responsibility and governmental accountability. As councilman, Nirenberg brought together a public-private coalition to save the world-renowned Bracken Bat Cave, the largest colony of bats in the world.

Nirenberg was first elected as Mayor on June 10, 2017. He was re-elected to a second term on June 8, 2019.

During your career what accomplishment(s) regarding water are you most proud of?

I am most proud of the work I’ve done to protect the Edwards Aquifer — San Antonio’s main source of drinking water and one of the most efficient sources of clean groundwater in the world. And we are connecting water resources to our city’s comprehensive planning strategy.

My work in that regard includes crafting a deal to save the Bracken Bat Cave, which hosts the largest colony of bats in the world and is a critical recharge feature for the Edwards Aquifer.

In 2015, I led the effort to continue and expand the Edwards Aquifer Recharge Protection Program, which has preserved 160,000 acres of land over the aquifer’s most sensitive areas, including pilot projects to protect recharge in urban areas. This year, I am working to establish a sustainable revenue source to extend the program into future.

I led the effort to ban coal tar sealants from use in San Antonio.

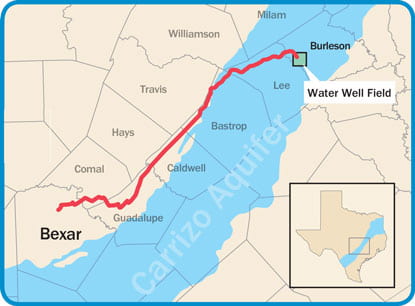

From a state-level view, San Antonio’s largest step forward on water during my tenure in government has been the Vista Ridge Pipeline Project, which will be bringing groundwater 142 miles from the Carrizo/Simsboro Aquifers in Burleson County to San Antonio. The pipeline project ties regional water stewardship to our need to ensure long-term water supply for one of the fastest growing urban populations the nation. The pipeline will be in full operation this summer.

Vista Ridge will bring as much as 50,000 acre-feet annually to San Antonio, becoming our largest source of non-Edwards Aquifer water. I thoroughly examined the project from all viewpoints, and even met with landowners in Burleson County, before I decided to support the pipeline. I wanted to be sure we were on the right path.

Not only is the pipeline a huge breakthrough for San Antonio — giving us unprecedented water security — it also is an important pacesetter for Texas. Regional sharing projects are essential as Texas strives to provide water to all regions of our fast-growing state.

San Antonio is often held up as a national success story regarding water conservation, particularly with regard to reducing its per capita water use. Do you ever hear from the mayors of other large cities who want to know how to replicate San Antonio’s success in water conservation?

Through the work of my predecessors, San Antonio has truly earned its reputation for success in conserving water. Considering our history of droughts, I would say San Antonio’s conservation history is a “necessity is the mother of invention” story.

Much of the trailblazing work began in earnest in the 1990s when environmental law began to recognize the need to manage underground water as a shared resource.

My peers from around the nation — and around the world — still ask about our programs and visit San Antonio regularly to see how we manage our water system and protect our water sources. I tell them the conservation and environmental protection efforts are absolutely worthwhile.

In the near term, the water you save through conservation is the least expensive water of all, and in the long term, these efforts are critical to the viability and enjoyment of our community for future generations.

Few major cities are as fortunate as San Antonio to have access to tremendous natural treasure like the Edwards Aquifer. Can you describe San Antonio’s efforts to preserve lands within the contributing and recharge zones of the aquifer?

During the last 20 years, San Antonio has protected sensitive recharge features and undeveloped land on the aquifer’s recharge zone by purchasing land as well as buying conservation easements.

This approach allows us to protect recharge into the aquifer and avoid clashing with Texas’ strong property rights laws and philosophies.

We have protected more than 160,000 acres through the Edwards Aquifer Protection Program. We have invested more than $268 million in the effort. This year, we are in the process of changing the funding mechanism from sales tax to ensure long-term program sustainability amid a complexity of needs, but I expect the program to continue for some time.

San Antonio is located in a region that experiences frequent droughts, but portions of the same region are also referred to as “Flash Flood Alley.” What are some of the challenges that these weather extremes present for local government?

One of the biggest challenges is one that will confront more and more communities because of climate change. That challenge is building infrastructure capable of coping with increasingly severe weather events — droughts and floods.

Urban flooding is changing the type of storm sewer systems, bridges and other infrastructure we need. Storms such as Hurricane Harvey, which devastated parts of Houston, overwhelm infrastructure built with traditional flooding expectations in mind.

The cost of being prepared for 1,000-year storms such as Hurricane Harvey is astronomical and prohibitive. A City of San Antonio study showed that an $8.7 million bridge built to survive a 100-year flood would have cost $37.1 million if built to survive a Harvey-sized event.

That is just one of many reasons that our Climate Action and Adaptation Plan was a necessity. We have to act deliberately to be resilient and sustainable.

Is there anything you think that state government should or should not be doing regarding water that would help San Antonio’s water management efforts?

For Texas to remain viable in the future, state lawmakers must recognize the reality that it has become an urban state and will continue to urbanize in the future. That absolutely requires us to develop a functional water plan to manage underground water resources effectively. And that requires us to end the “rule of capture.”

What do you think is the biggest future challenge facing San Antonio with regard to water?

While we have addressed our water supply issue for the foreseeable future with a variety of conservation and diversification efforts, we must remain vigilant to ensure we will always maintain an adequate clean supply. We must also maintain affordability while ensuring the upkeep of the delivery infrastructure.

As long as we succeed in securing our supply at a reasonable cost, coping with the extreme floods and droughts caused by climate change will be the most pressing near-term problem related to water.

Are there any other thoughts regarding water that you would like to share with us?

I believe San Antonio, which struggled for decades to address its supply issue, shows that proper water management can address modern urban problems, but we must remember that the cooperation of regional neighbors is essential for us all to manage our water resources.

Question: Is there anything you think that state government should or should not be doing regarding water that would help San Antonio’s water management efforts?

The Mayor’s response is to end the Rule of Capture, also known as the Law of Biggest Pump.

If this actually happened, he should in turn be prepared to ask the Legislature to enhance the powers and provide the resources required to manage groundwater equitably for all Texans.

This is because groundwater in Texas is private property, but it is also subject to reasonable regulation by Groundwater Conservation Districts (GCDs).

These districts are the State’s preferred method of groundwater management as it has been since the first one was created in 1951.

According to the Texas Water Development Board: “Confirmed GCDs (including two subsidence districts and the Edwards Aquifer Authority) are located partially or fully within 173 of 254 Texas counties.”

Created with specific powers to meet local conditions by the Legislature, these districts manage groundwater through a board of elected Directors who are typically unpaid volunteers supported by a small staff.

As one size cannot fit all in a state as big as Texas, the effective management of this resource admittedly varies, and in some cases, this can be traced to the Legislature that creates one.

It also depends on what these districts can, and cannot do, by law through the Texas Water Code.

As it is the GCD that can limit the Rule of Capture today, ending it to satisfy one request may well create a much bigger problem for the rest of us who depend on water pumped from aquifers.

In no small part this is because property rights still matter to those who own their land.

Texas has shifted politically to favor satisfying growing urban centers and their water needs, but water must also be available to support the production of their food and fiber from rural Texas.

From that perspective, enhancing the existing groundwater management structure would be both wise and practical if Texas is to maintain a balanced, healthy economy for all.

Milan J. Michalec

Director, Pct 2. and President, Cow Creek Groundwater Conservation District

Kendall County

Mayor Nirenberg has denied San Antonio voters the right to vote to renew the Edwards Aquifer Protection Program or not. Please check out https://therivardreport.com/city-officials-propose-keeping-aquifer-protection-program-in-house/

Our water bills have skyrocketed because of the Vista Ridge pipeline. The most recent in a series of rate hikes was 10% effective January 1, 2020. These rate hikes are harming the poor and seniors on fixed income.

Mayor Nirenberg and his allies are now planning on diverting Edwards Aquifer protection funding to our local municipal bus service. We need water to survive not more empty buses.

Bob Martin, President

Homeowner-Taxpayer Association of Bexar County

The Mayor says of San Antonio’s water supply, “We must also maintain affordability…” of “an adequate clean supply.” Who is ACCOUNTABLE for this outcome?

City Ordinance #75686 established SAWS in 1992, making SAWS subject to City Council leadership, but City Council does not lead. City Attorney Andrew Segovia, who reports to the City Manager and Mayor, will not enforce #75686, or even acknowledge its existence.

So SAWS does what any unregulated utility monopoly would do — ANYTHING IT WANTS.

Please note that a citizen’ movement — across the ideological spectrum in San Antonio, including Sierra Club, LULAC and Homeowner-Taxpayers Assoction, and more — just kicked off a municipal petitoin drive to allow SA Voters the opportunity to pass their very own, “SAWS Accountability Act”. (See SAWSActPAC.org for details.)

Also, Mayor Nirenberg might have a bad memory:

1. When he met with Burleson landowners about Vista Ridge, he promised to bring forward a mitigation plan for them if (when!) the massive mining operation of the areas’ groundwater does harm to people’s wells, groundwater availability and the aquifer itself. No such plan has ever been brought to them by the Mayor or SAWS or the private partner in this shadowy “public-private partnership.” That’s why it’s called “The San Antone Hose.”

2. Then City Councilman, now Mayor, Nirenberg was warned when big real estate rammed Vista Ridge on San Antonio ratepayers, it would come back around to bite them again by threatening the conservation of the Edwards. Nirenberg and other Council members (a majority of them) are in process of ratcheting back and even destroying Edwards protections. He talking points are severe “manipulation of the truth.”

Hoping the Trib will cover the other side of this fight going on now for years from Burleson to Bexar Counties.

Thanks. Linda Curtis, League of Independent Voters of Texas