SUMMARY:

- The last month was dry for most of the state, but…

- …with recent rains along the Gulf Coast, statewide drought conditions have decreased.

- We anticipate improving drought conditions along much of the Gulf Coast and Lower Rio Grande areas with persistent drought flirting with the Texas Panhandle.

I wrote this article on April 24 and 26, 2020.

I was never much into Megadeth, but I am all over medieval megadroughts. Megadroughts are multi-decadal droughts identified through tree-ring analysis (the thinner the ring, the less precipitating). A recent paper published in Science posits that the American Southwest is amidst a severe megadrought, the worst 19-year period in 500 years and the second worst on record. Although the drought centers on the (other) Colorado River basin, its claws reach out at least to the Rio Grande (impacting the El Paso area).

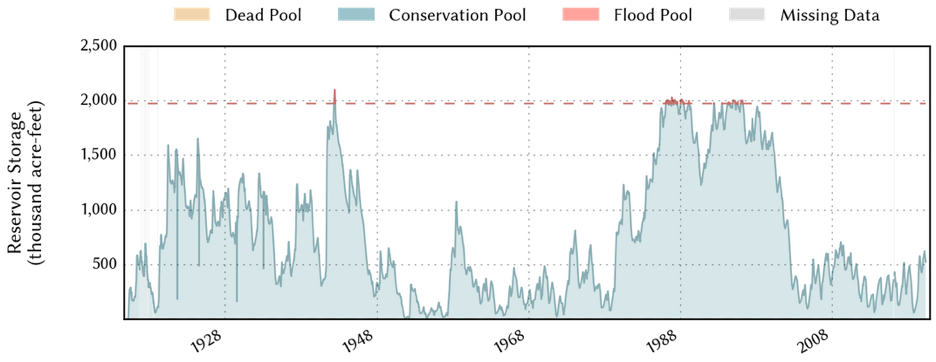

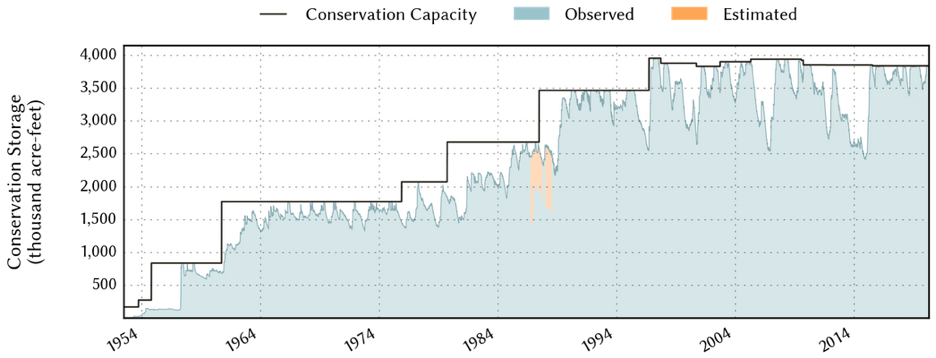

Conservation reservoir storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir on the Rio Grande in New Mexico, an important source of water to El Paso and area irrigators, has responded to the drought almost like a square wave with low storage levels since 1999 (Figure 1). I suspect West Texas reservoirs may also be impacted by the drought in the southwest where, similarly, reservoirs have dropped severely since the late 1990s (see, for example, O.H. Ivie and Lake Meredith, among others).

The Science paper also proposed that the current drought is worse because of climate change, moving it from what would have been the 11th worst on record to its current second place. In other words, climate change didn’t create the drought but has made it worse than it would have been. Scientists are currently arguing over whether the current drought is a megadrought, a discussion frustrated by the lack of a consensus definition of what exactly a megadrought is (which makes me wonder if Megadeth was, perhaps, just Deth). Also, if the current drought is, indeed, a drought, that suggests that what the Southwest is currently experiencing is not a new normal, something suggested by earlier papers.

Figure 1: Conservation storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir since inundation (source).

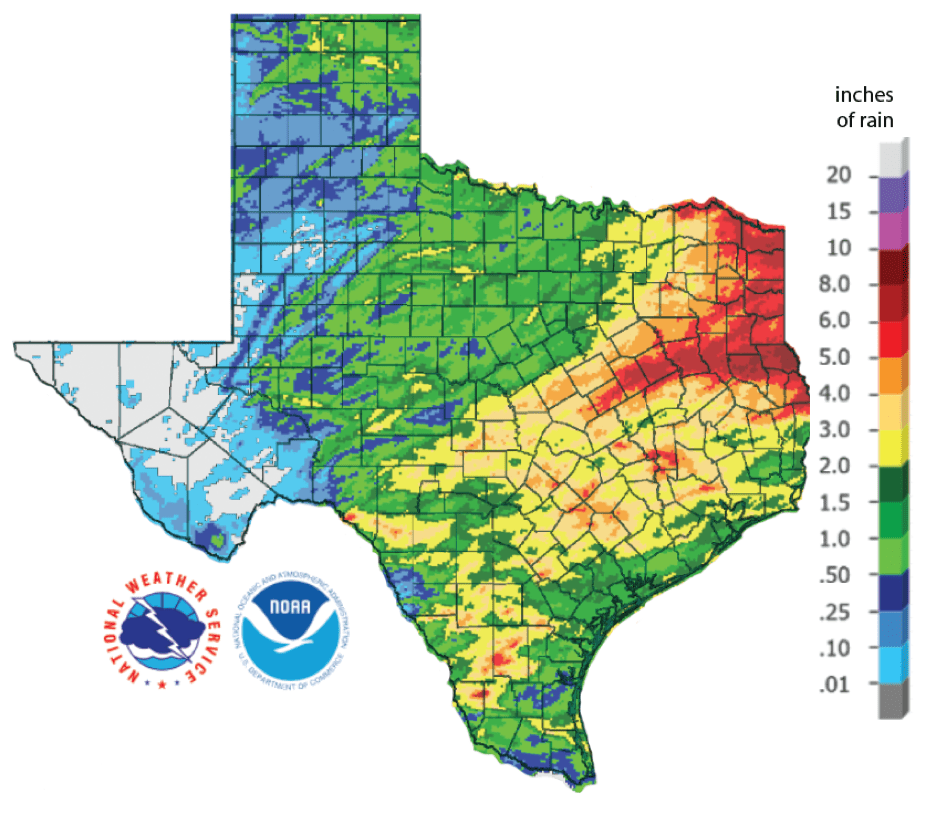

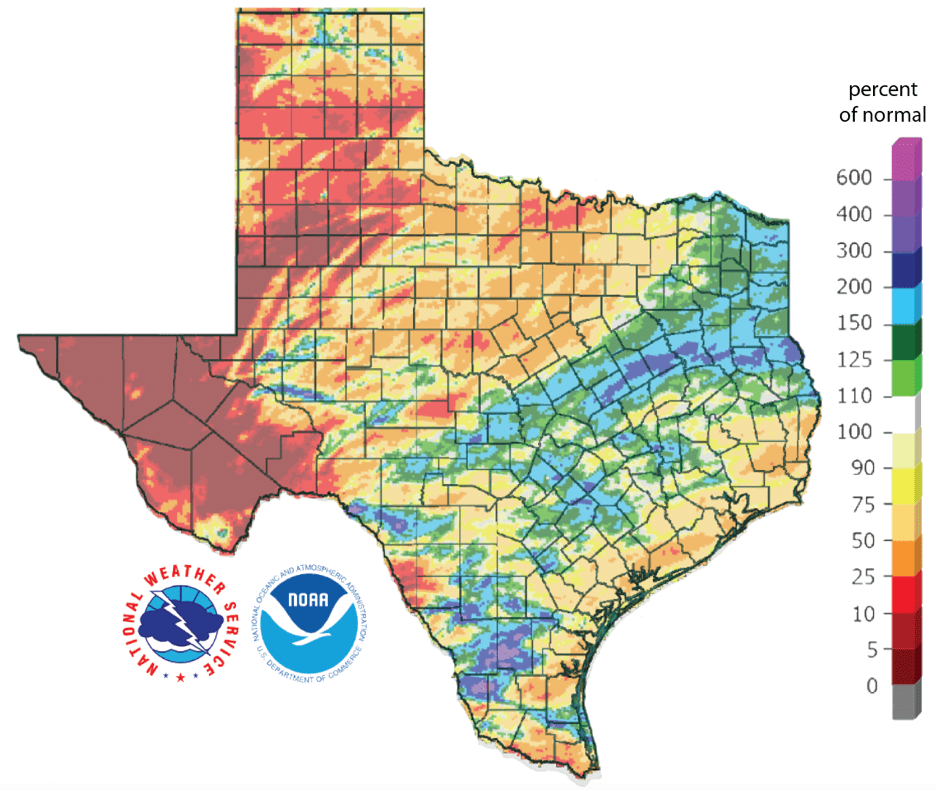

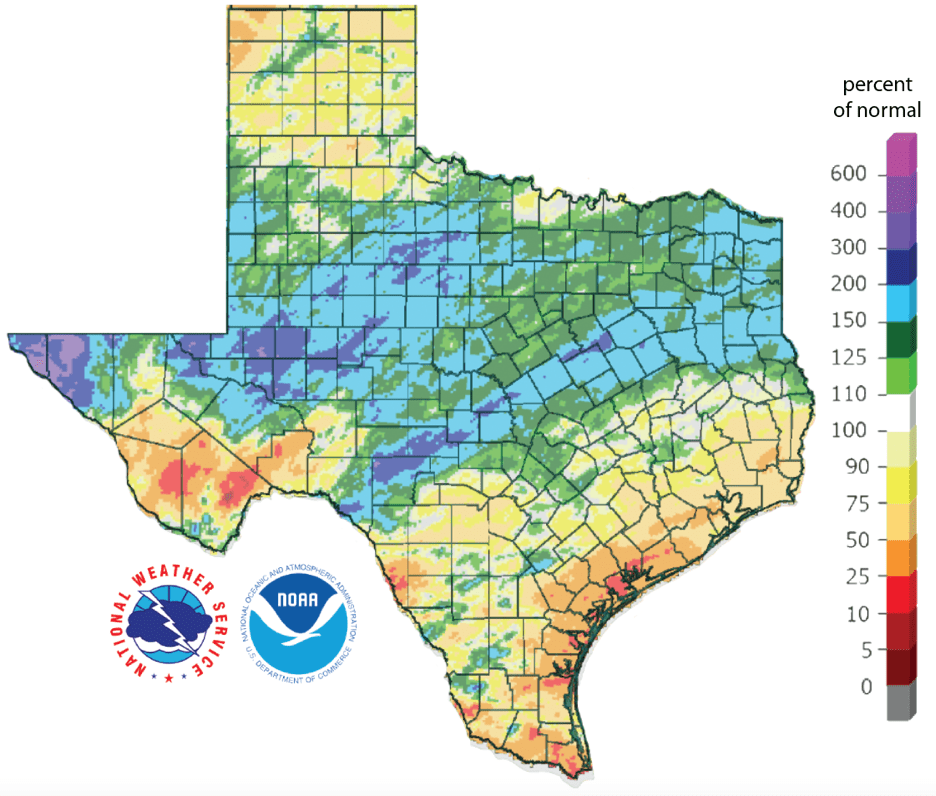

Several fronts that passed through the eastern half of the state over the past month left behind more than two inches of rain and, in some cases, more than six inches (Figure 2a). Most of the state received less than normal rainfall over the past four weeks with much of West and Far West Texas getting less than 25 percent of normal (Figure 2b). Looking back 90 days, Big Bend, the Gulf Coast, and the Lower Rio Grande Valley have suffered substantially below normal rainfall (Figure 2c).

Figure 2a: Inches of precipitation that fell in Texas in the 30 days before April 24, 2020 (source). Note that cooler colors indicate lower values and warmer indicate higher values (and note that the light grey color in Trans-Pecos Texas should be dark grey).

Figure 2b: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the past 30 days as of April 24, 2020 ( source).

Figure 2c: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the past 90 days as of April 24, 2020 (source).

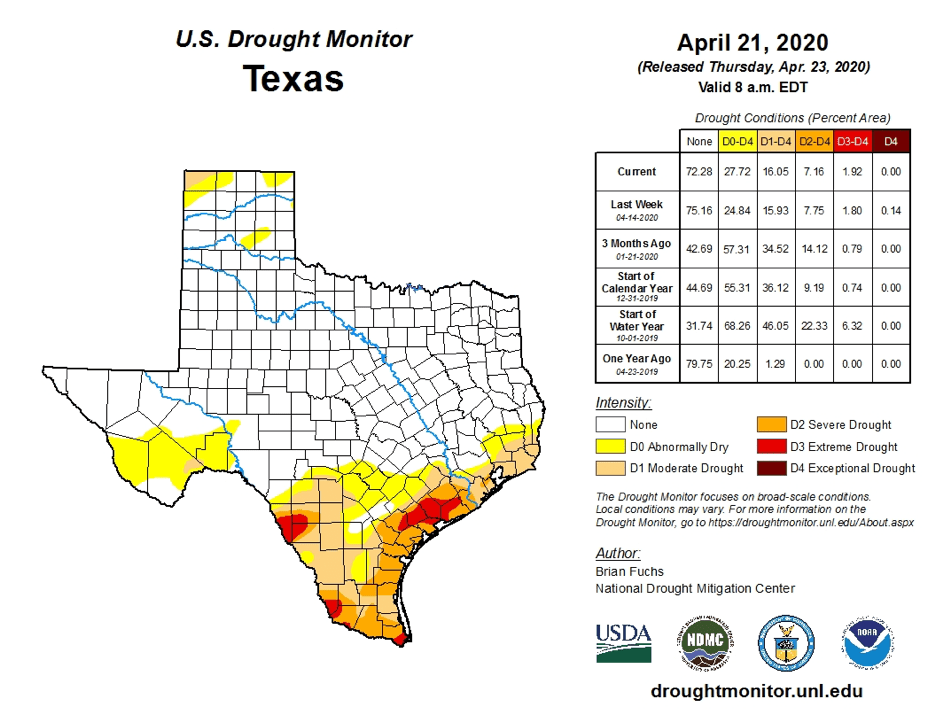

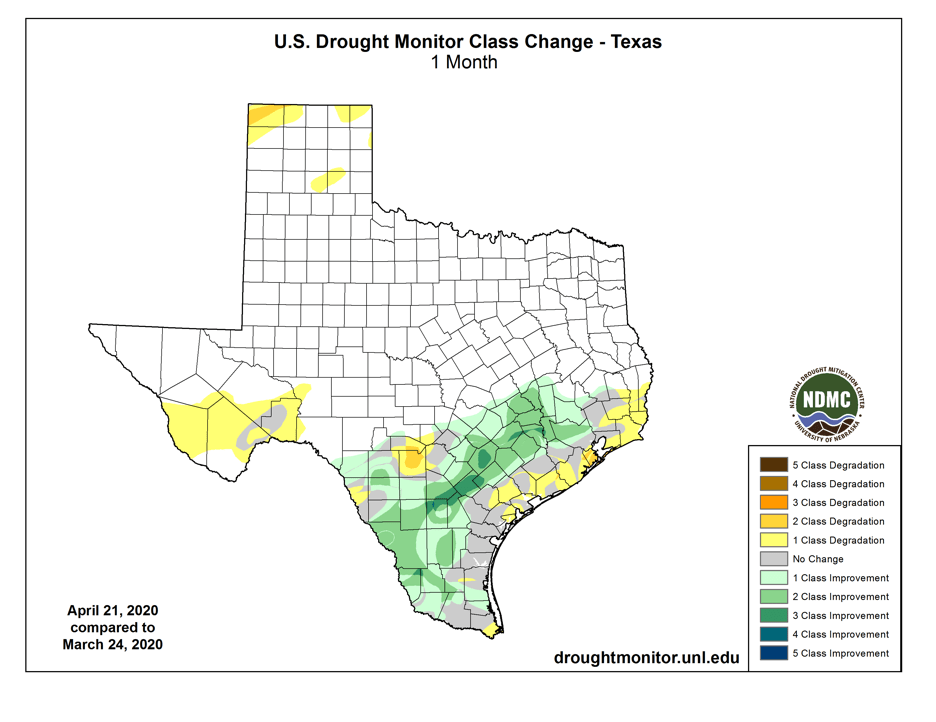

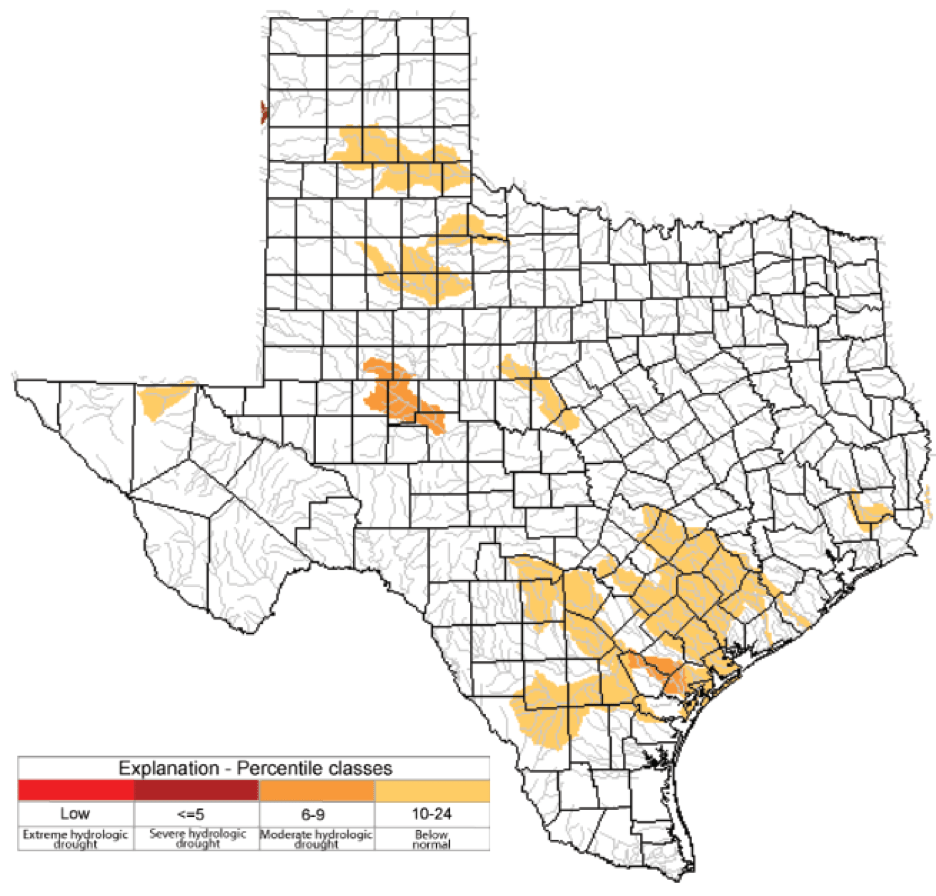

The amount of the state under drought conditions (D1-D4) decreased from 19.8 percent four weeks ago to 16.1 percent today (Figure 3a). Rains over the past month decreased drought along the inner Gulf Coast while drought developed up in Dallam County in the Texas Panhandle (Figure 3b). About 2 percent of the state is experiencing extreme drought with exceptional drought disappearing from the state (Figure 3a). About 28 percent of the state is abnormally dry or worse (D0-D4; Figure 3a), up from 26 percent four weeks ago.

Figure 3a: Drought conditions in Texas according to the U.S. Drought Monitor (as of April 21, 2020; source).

Figure 3b: Changes in the U.S. Drought Monitor for Texas between March 24, 2020, and April 21, 2020 (source).

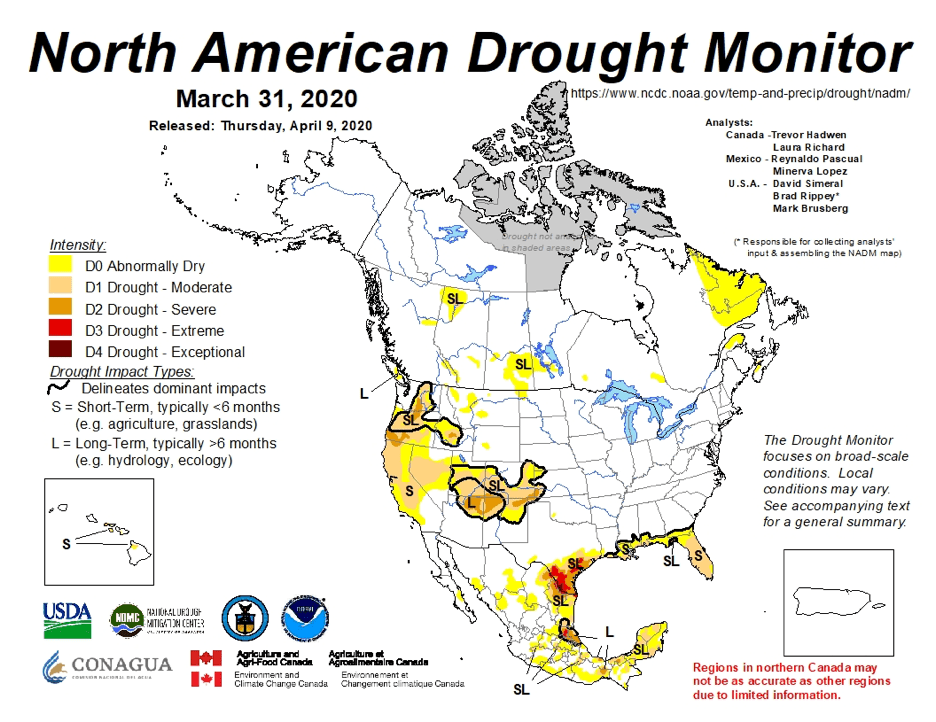

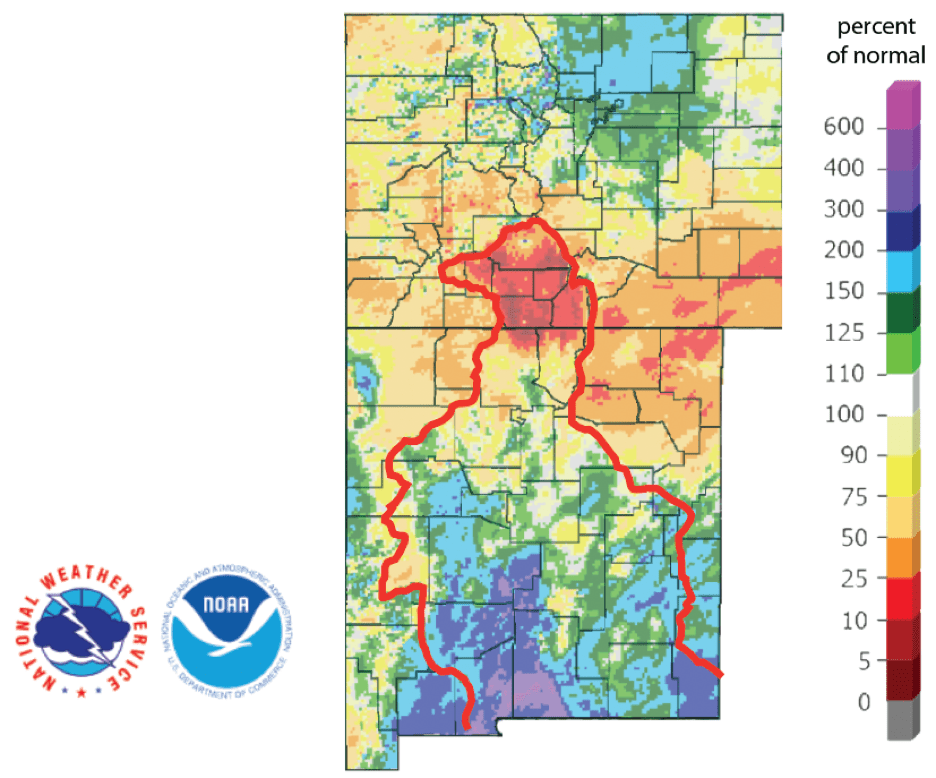

The North American Drought Monitor for February continues to show severe drought in the headwaters of the Rio Grande in southern Colorado, a significant source of water for Elephant Butte Reservoir which is, in turn, a significant source of water for the El Paso area (Figure 4a). Precipitation in the Rio Grande watershed in Colorado over the last 90 days is less than 25 percent of normal for much of the watershed in a seemingly endless drought for the region (Figure 4b). Conservation storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir decreased from 29.0 percent full a month ago to 26.5 percent on April 26, 2020. The Rio Conchos basin in Mexico, an important source of water to the lower part of the Rio Grande in Texas, has a small area of abnormally dry conditions at the southeastern end of the basin (Figure 4a).

Figure 4a: The North American Drought Monitor for March 31, 2020 (source).

Figure 4b: Percent of normal precipitation for the past 90 days for Colorado and New Mexico as of April 26, 2020 (source). The red line is the Rio Grande Basin. I use this map to see check precipitation trends in the headwaters of the Rio Grande in southern Colorado, the main source of water to Elephant Butte Reservoir downstream.

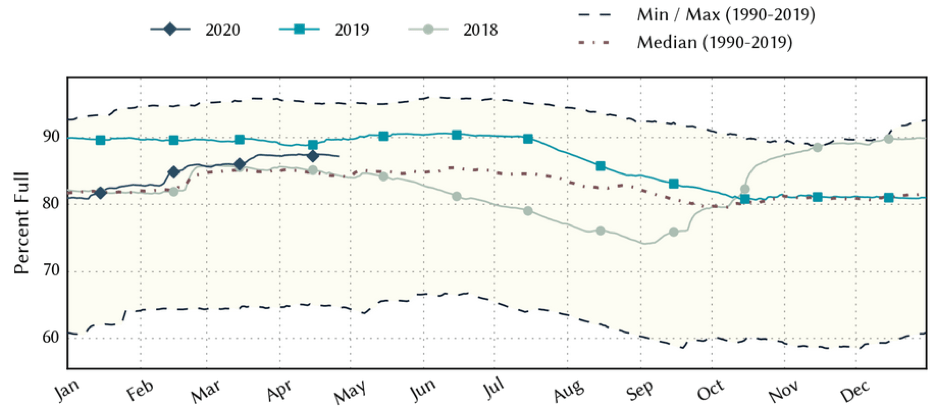

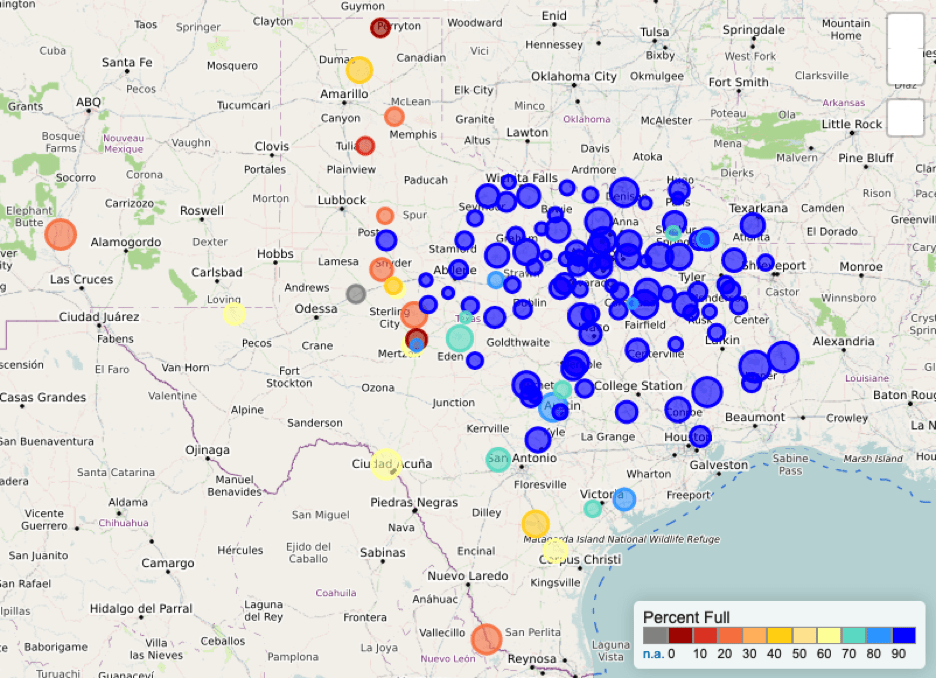

A number of streams and rivers along the central Gulf Coast had streamflows less than 25 percent of normal along with a smattering of other basins across the state (Figure 5a; thanks to James Dodson for turning me on to this analysis). Statewide reservoir storage is about the same as four weeks ago, sitting at 86.2 percent full, a few points above the median storage since 1990 for this time of year (Figure 5b). Storage in individual reservoirs remained relatively stable over the past month (Figure 5c). The reservoirs in the Dallas area are 99 percent full (Figure 5d).

Figure 5a: Parts of the state with below-normal seven-day average streamflow (source).

Figure 5b: Statewide reservoir storage since 2018 compared to statistics (median, min, and max) for statewide storage since 1990 (source).

Figure 5c: Reservoir storage as April 26, 2020, in the major reservoirs of the state (source).

Figure 5d: Reservoir capacity and storage in Dallas-area Reservoirs since the 1950s (source).

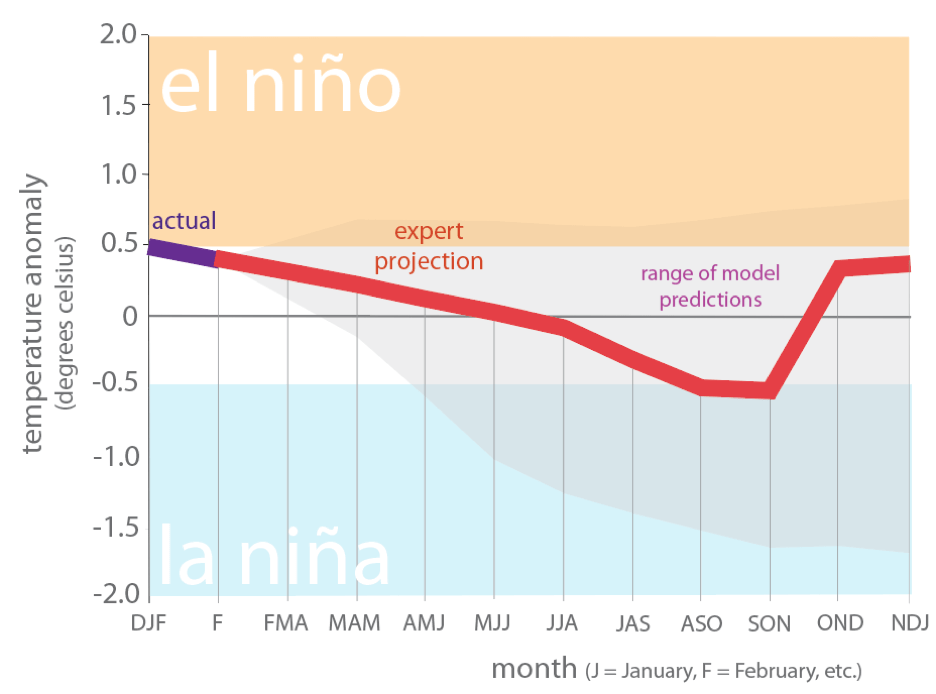

For the El Niño Southern Oscillation, we remain in neutral (La Nada) conditions (Figure 6). The Climate Prediction Center increased the chance of neutral conditions through the summer from 55 to 60 percent with neutral conditions “most likely” continuing through the fall. The herki-jerkiness toward the end of the year for the expert projection (which represents human judgement in addition to model output, aka The Borg Projection) is indicative of a growing probability of La Niña conditions in the winter.

Figure 6. Forecasts of sea surface temperature anomalies for the Niño 3.4 Region as of March 19, 2020 (modified from source).

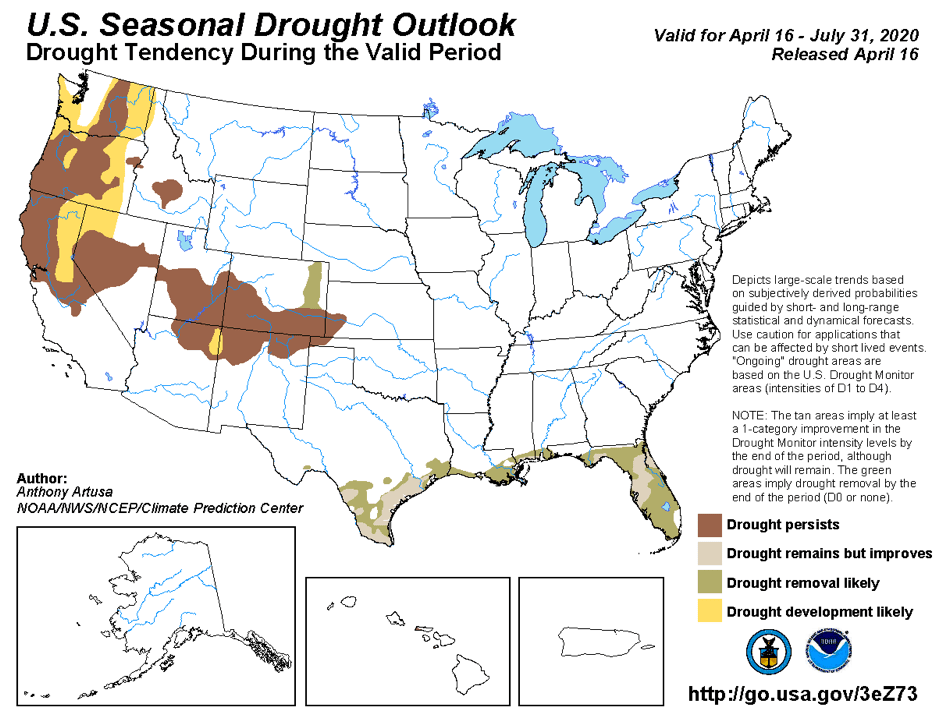

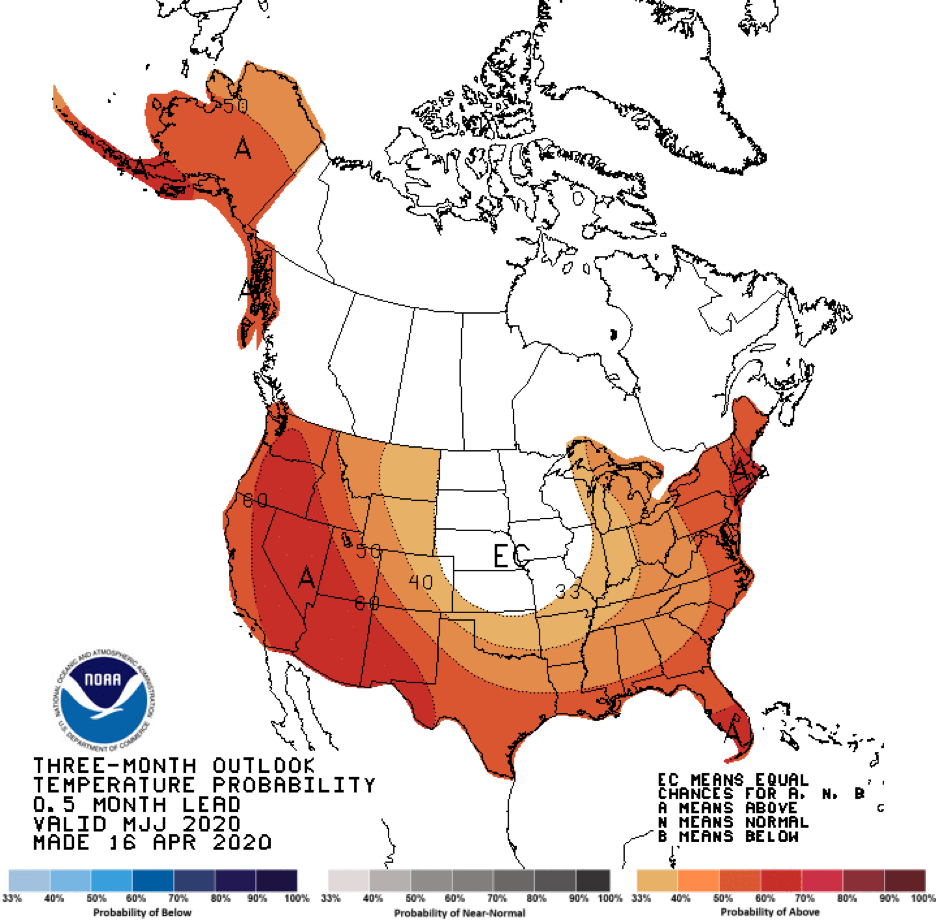

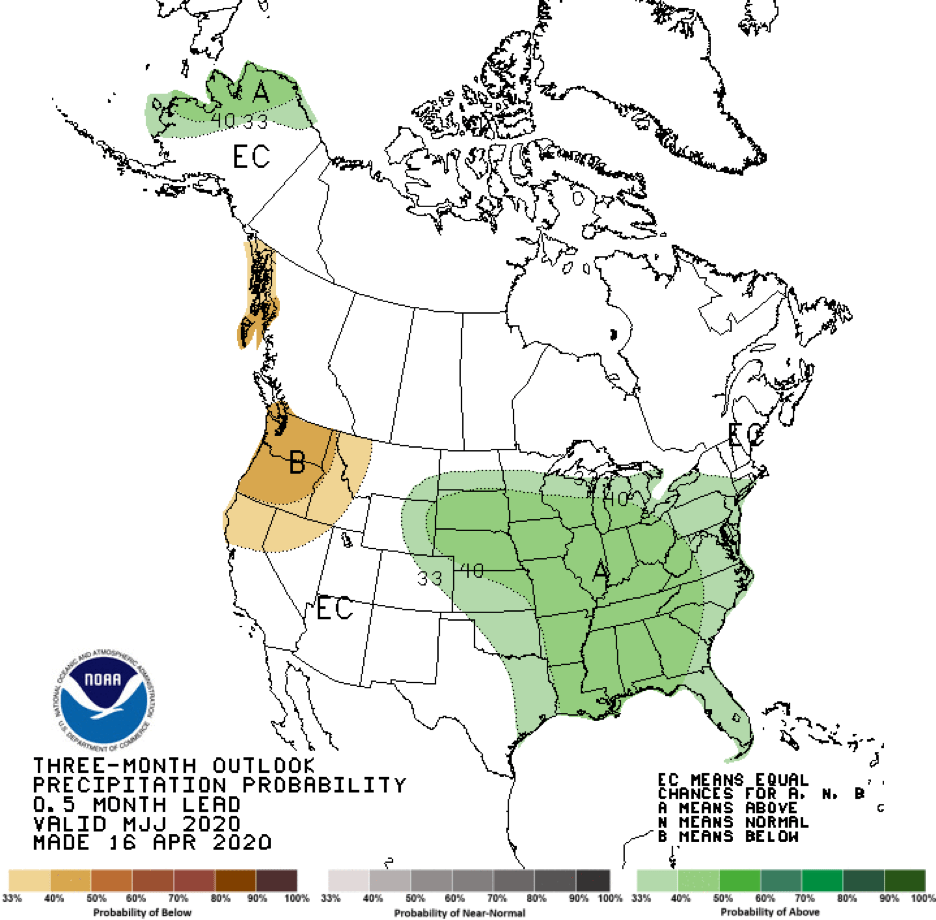

The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook through July 31, 2020, projects improving drought conditions along much of the Gulf Coast and Lower Rio Grande areas with likely drought removal in the greater Houston area and persistent drought flirting with the Texas Panhandle (Figure 7a). The three-month temperature outlook projects warmer-than-normal conditions statewide with greater warming to the west (Figure 7b) while the three-month precipitation projects wetter-than-normal conditions for the northeastern part of the state (Figure 7c).

Figure 7a: The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook for April 16, 2020, through July 31, 2020 (source).

Figure 7b: Three-month temperature outlook from April 16, 2020 (source).

Figure 7c: Three-month precipitation outlook from April 16, 2020 (source).

Author

Robert Mace

Interim Executive Director & Chief Water Policy Officer at The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment

Robert Mace is the Interim Executive Director and the Chief Water Policy Officer at The Meadows Center. He is also Professor of Practice in the Department of Geography at Texas State University. Robert has over 30 years of experience in hydrology, hydrogeology, stakeholder processes, and water policy, mostly in Texas.