With 38 public universities and 35 private colleges and universities in the state and many more across the country (and the world) interested in Texas, there’s a great deal of academic scholarship focused on water in the Lone Star State. In this column, I provide brief summaries to several recent academic publications on water in Texas.

Let’s start thinking about water!

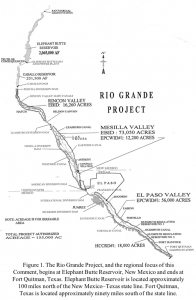

Payne, T.R, 2020, In (not so) deep water—The Texas-New Mexico water war and the unworkable provisions of the Rio Grande Compact: Texas Tech Law Review, v. 52, no. 669, p. 670-703.

Texas and New Mexico (and, technically, Colorado) have been in litigation over the Rio Grande since 2013. Payne presents a brief history of water management in the basin, Supreme Court interstate water compact jurisprudence, as well as an argument that the Rio Grande Compact is flawed because it’s frozen in time and, as a consequence, unworkable. Having worked a wee bit on the issue when I was with the state, I take issue with some of the arguments, such as the differences in groundwater law mattering and the provisions being unworkable (no mention of the agreement between New Mexican and Texan irrigation districts that avoided an earlier lawsuit?). Nonetheless, it’s interesting to read a different angle on the situation

Texas and New Mexico (and, technically, Colorado) have been in litigation over the Rio Grande since 2013. Payne presents a brief history of water management in the basin, Supreme Court interstate water compact jurisprudence, as well as an argument that the Rio Grande Compact is flawed because it’s frozen in time and, as a consequence, unworkable. Having worked a wee bit on the issue when I was with the state, I take issue with some of the arguments, such as the differences in groundwater law mattering and the provisions being unworkable (no mention of the agreement between New Mexican and Texan irrigation districts that avoided an earlier lawsuit?). Nonetheless, it’s interesting to read a different angle on the situation

Devitt, D.A., Young, M.H., and Pierre, J.P., 2020, Assessing the potential for greater solar development in West Texas, USA: Energy Strategy Reviews, v. 29.

When considering solar, there’s the obvious thing to consider: sunlight (what the smart kids call solar irradiance). And then there’s the less-obvious thing: water. Water? Yep, water. In part, it depends on what type of solar you’re considering. Solar troughs and solar towers focus sunlight to generate steam which is then used to spin a traditional steam turbine and then requires cooling. Devitt and others note that solar troughs and towers with wet cooling consume water at nearly twice the rate of fossil-fuel technology with a 400-megawatt plant in Arizona consuming several thousand acre-feet per year. Photovoltaics use much less water but still require some for washing, something that was an issue with a proposed solar field near Marfa a number of years ago. Large solar farms also create their own microclimates, even warming soil beneath them 10 °C more than the surface of the panel. With vegetation cleared for photovoltaics, daytime temperatures above the panels can be 3 to 4 °C warmer than unaltered land. And then, given the height and orientation of the panels, they serve to transfer that heat as much as 400 meters into the surrounding landscape. The intent of the article is not to beat up on solar, but to note that there are environmental consequences to consider with solar as well.

Meeks, M., and Chandra, A., 2020, Drought response and minimal water requirements of diploid and interploid St. Augustinegrass under progressive drought stress: Turfgrass Science, DOI: 10.1002/csc2.20012 [link]

Since turfgrass is outside my expertise, the first thing I learned is that, no, St. Augustinegrass is not a typo. That’s exactly how the turf testers spell it. The next thing I learned is that there are a number of different St. Augustinegrasses (for example, Floritam, Amerishade, DelMar, Palmetto, Raleigh, Sapphire and Texas Common) with the San Antonio Water System only allowing the more drought-resistant one (Floritam) for landscape use in their service area. With a growing population and, therefore, a growing turfgrass area, St. Augustinegrass’ high evapotranspiration rate of 5.8 millimeters (about a quarter of an inch) per day has implications for water resources and resiliency. Through an exciting-sounding process called “embryo rescue,” Texas A&M has developed interploid hybrids to enhance the water efficiency of St. Augustinegrass, including one named TamStar. Whereas Palmetto would require about 13,000 gallons and Floratam would require 9,300 gallons for an average-sized yard in Dallas for 2015 and 2016, TamStar required (wait for it, wait for it…) no water to achieve the same aesthetic results. The paper did leave me with one unanswered question: can I get TamStar at Home Depot?

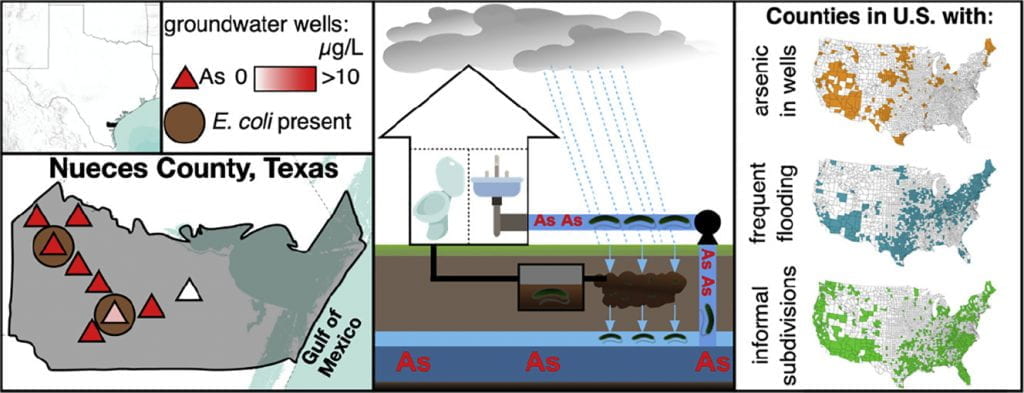

Rowles, III, L.S., Hossain, A.I., Ramirez, I., Durst, N.J., Ward, P.M., Kirisits, M.J., Araiza, I., Lawler, D.F., and Saleh, N.B., 2020, Seasonal contamination of well-water in flood-prone colonias and other unincorporated U.S. communities: Science of the Total Environment, v. 740 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140111

Colonias refer to developments in unincorporated areas where water and wastewater infrastructure, either by mis-design or fraud, do not meet minimum health and construction standards. Some homes don’t have a water supply and must haul water in, some homes don’t have any on-site wastewater treatment and discharge to cesspools or an unpermitted septic tank and some homeowners have dug their own wells that are too shallow and too close to wastewater discharges. Although a nationwide issue, Texas leads the country with more than 1,800 colonias as compared to New Mexico (142), Arizona (86) and California (15). This paper focused on colonias in Nueces County and found seasonal variations of arsenic and bacterial contamination that correlate with rainfall. A national analysis suggests that similar contamination issues could exist across the country.

Scanlon, B.R., Ikonnikova, S., Yang, Q., and Reedy, R.C., 2020, Will water issues constrain oil and gas production in the United States? Environmental Science & Technology, v. 54 https://dx.doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.9b06390

Since this paper was published in February, the oil and gas industry has faced far more serious concerns than water supply such as price wars between Saudi Arabia and Russia that sent West Texas crude prices negative and a pandemic-induced recession that has suppressed energy demands. However, the Saudis and Russians have come to terms and (please, please, for the love of Zeus!) we should have a vaccine soon for the outbreak, meaning that, at some point, oil and gas production—and their potential impacts on water supplies—will return. Previous global studies on unconventional oil and gas (that is, fracking) indicated water scarcity issues in semiarid regions. However, global studies almost always miss local and regional nuances that determine actual outcomes. For example, the aforementioned global study assumed the sustainable development of groundwater, something that isn’t exactly practiced in Texas. Nonetheless, with 55 times more water expected to be produced from the Permian Basin, even the planned depletion of local aquifers may strain under projected water use. In the Permian Basin, the authors show that projected water use by all sectors, including for fracking, amounts to 112 percent of the current modeled available groundwater while in the Eagle Ford it amounts to 250 percent of the current modeled available groundwater. Note that I added “current” before “modeled available groundwater”: desired future conditions and, in response, modeled available groundwater values can (and do) change with time and may accommodate increased demands, especially if voters expect to benefit economically. Nevertheless, can the Carrizo-Wilcox Aquifer supply 2.5 times more water than currently envisioned for South Texas?

Join Our Mailing List

Subscribe to Texas+Water and stay updated on the spectrum of Texas water issues including science, policy, and law.