SUMMARY:

- The past four weeks have been horribly dry with most of the state receiving less than 10 percent of normal rainfall.

- Large areas of exceptional drought are now in place on the High Plains and in the Big Bend area.

- Drought conditions are projected to persist and spread across Texas.

I wrote this article on October 25, 2020.

There’s a lot to note this month on weather and water. At the time I wrote this, the 2020 Atlantic Hurricane Season has tied 2005 for the greatest number of named storms at 27. Zeta is expected to hit the Gulf Coast on the 28th but at a good distance away from Texas. The official hurricane season ends November 30, so we still have a ways to go before we are done.

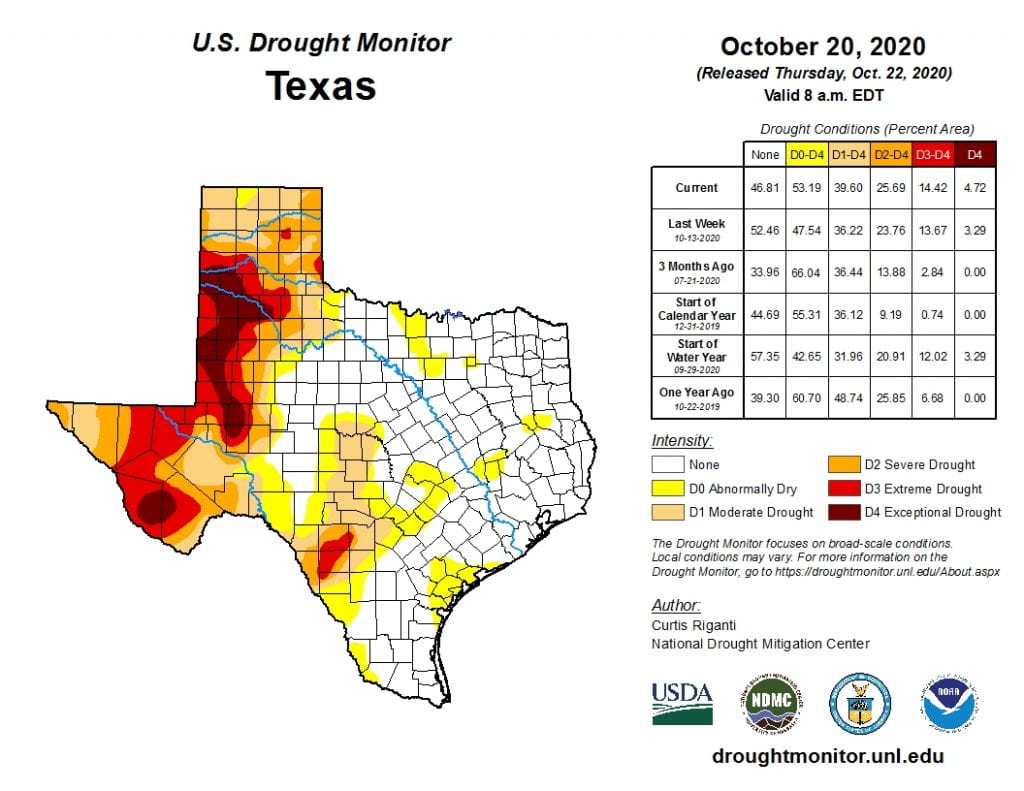

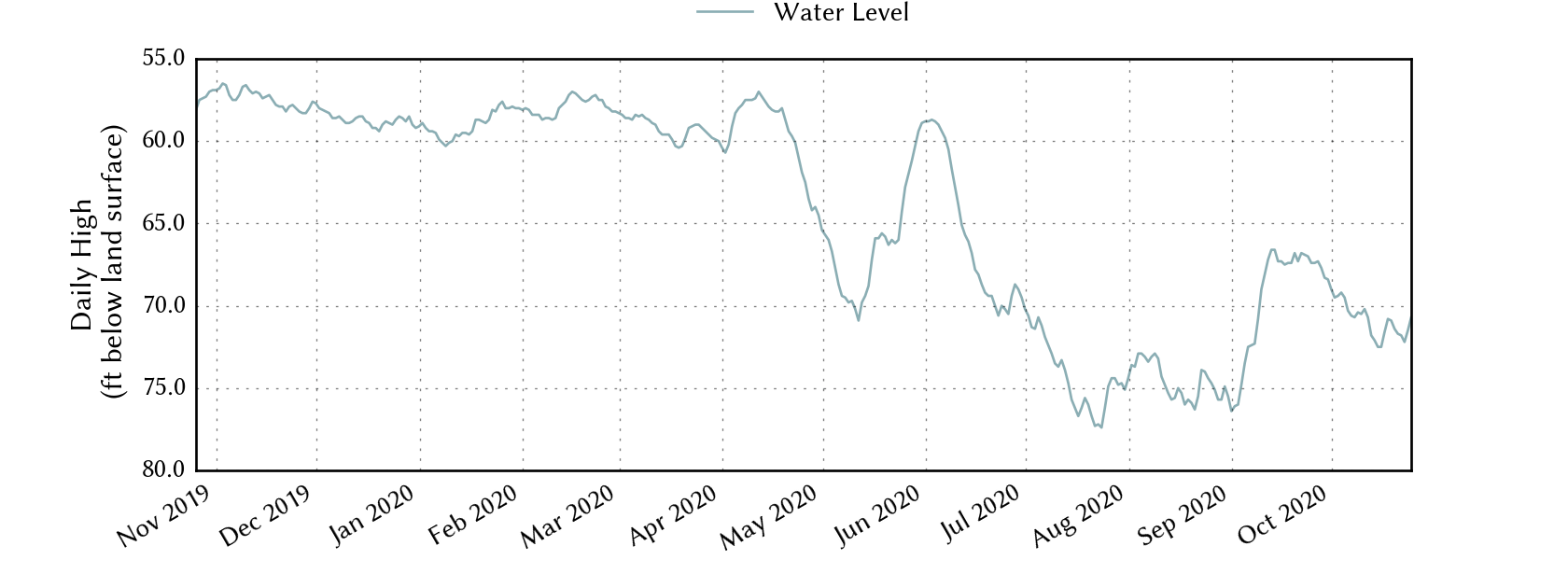

Drought’s deadly fingers, presumably powered by La Niña conditions, have firmly grasped the western half of the state and left the last four weeks with almost no precipitation for about half of the state. In response to lowering water levels in the aquifer (Figure 1), the Edwards Aquifer Authority declared Stage 1 pumping restrictions for the San Antonio Pool, which requires permit holders to reduce their authorized pumping amount by 20 percent. Drier and warmer conditions are expected to persist for entire state over the next three months and drought is expected to persist and expand across almost the entire state over the next three months. With a ~60 percent chance of La Niña conditions persisting through the spring (thus potentially connected a dry winter and spring with our traditionally dry summers), this is a drought to keep an eye on.

In a bit of good news, Mexico announced last week that they would release water from reservoirs in the Rio Conchos to comply with provisions on the 1944 treaty between Mexico and the United States on sharing surface water resources between the two countries. The release of water from Mexican reservoirs has been controversial there, especially with ongoing drought conditions.

Figure 1: Depth to water in J-17 in the Edwards Aquifer over the past year (source).

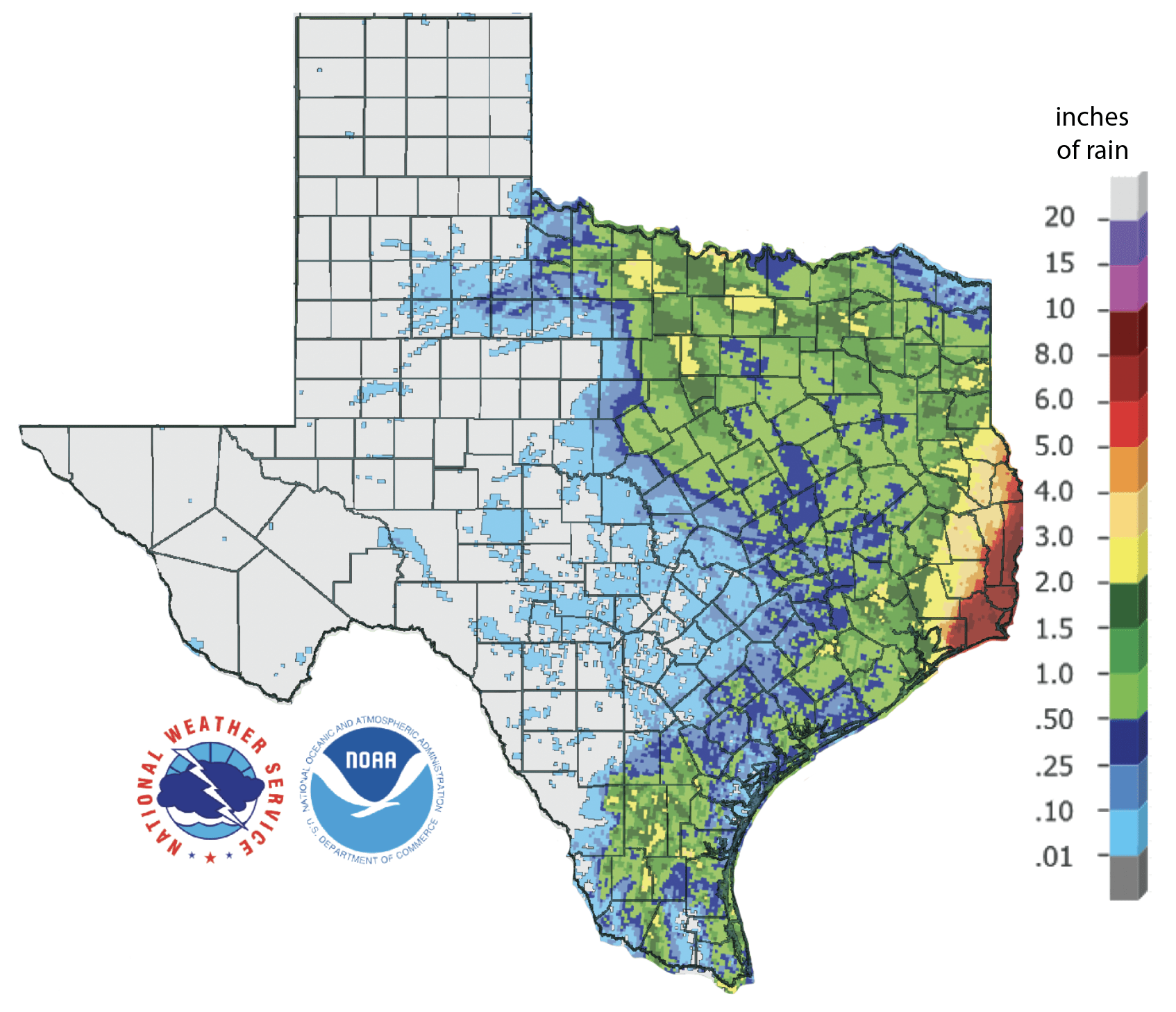

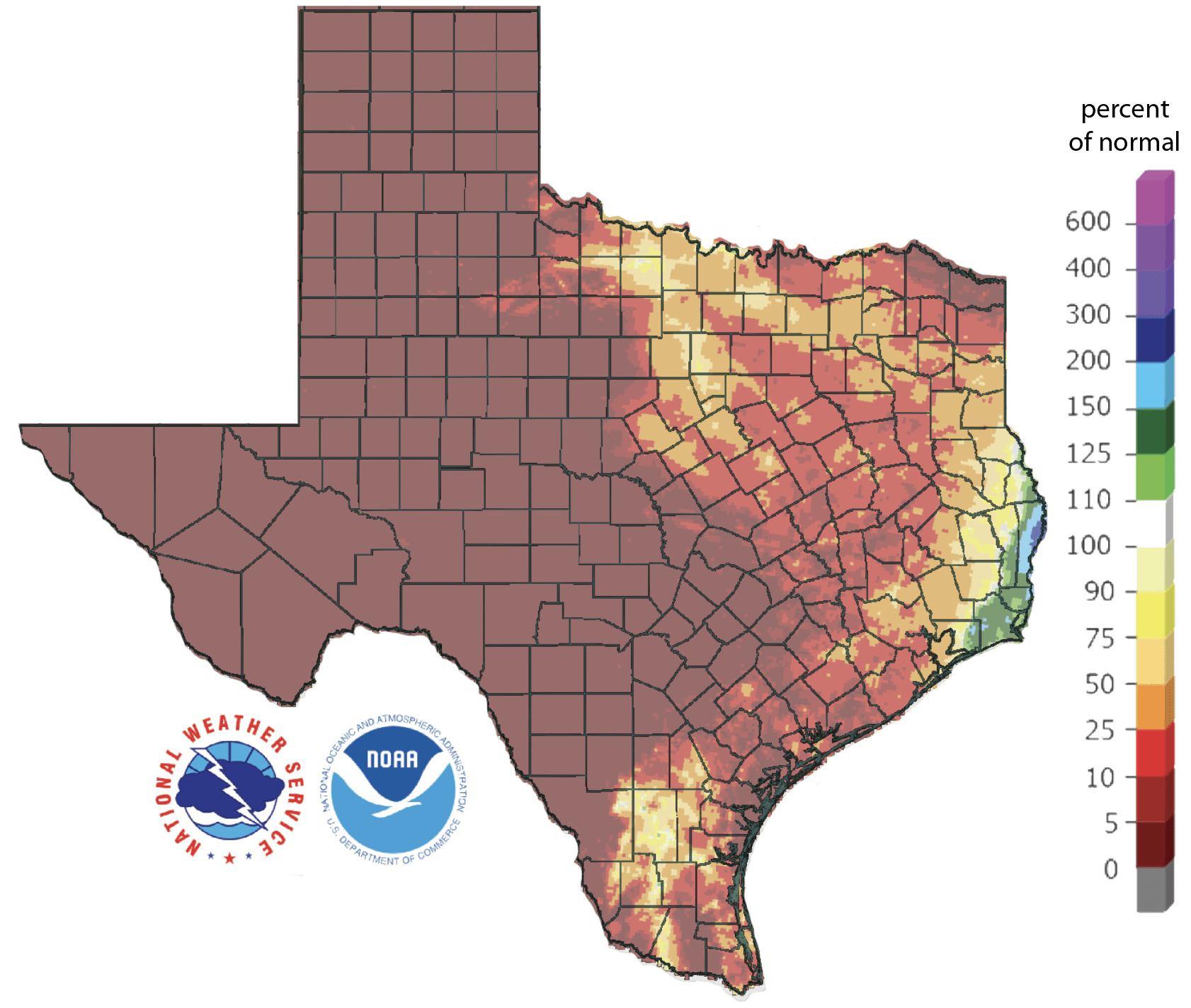

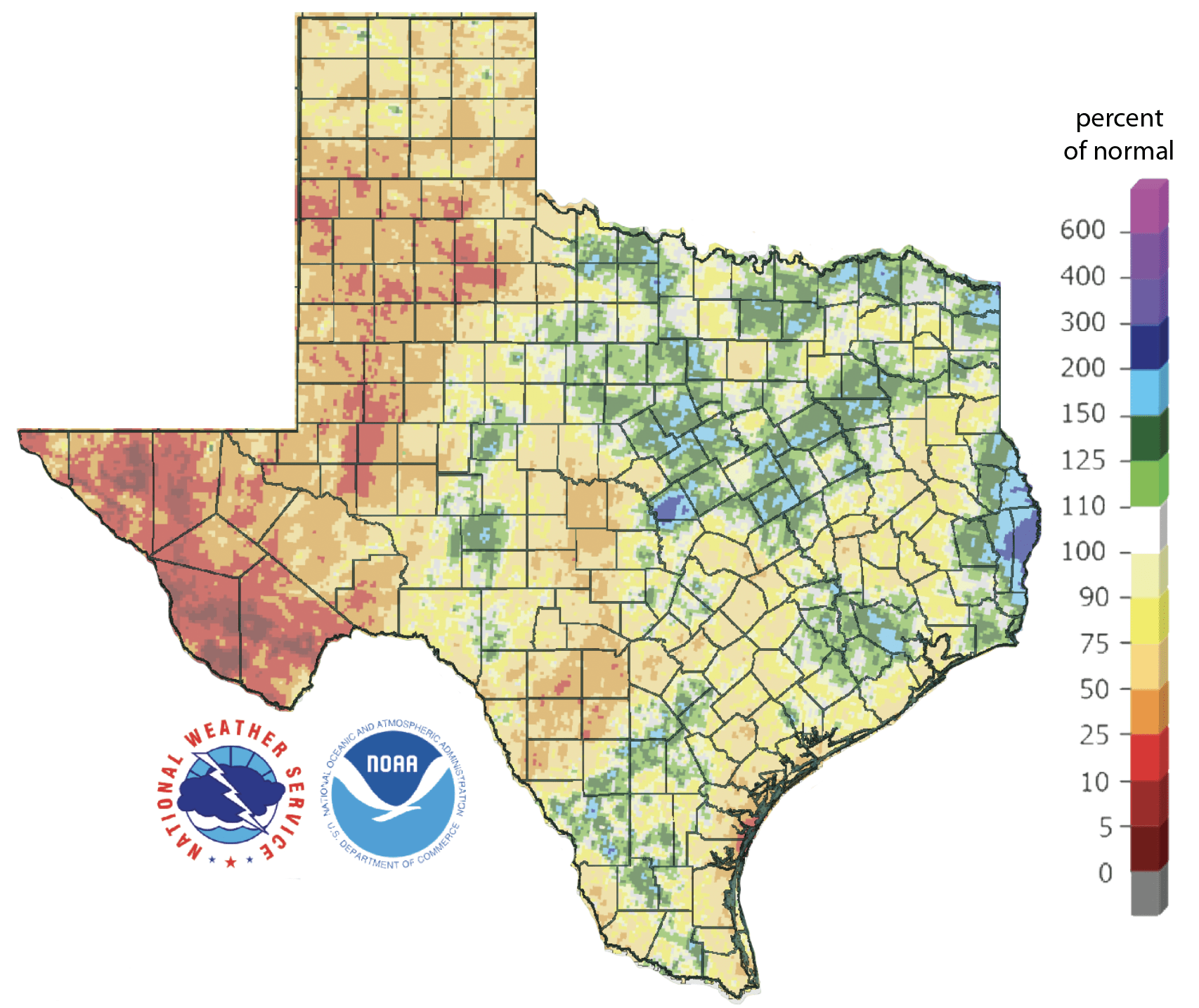

The rain spigot slammed shut over the past four weeks leaving most of the state with less than 0.10 inches of rain (and perhaps half the state with less than 0.01 inches; Figure 2a). This dry spell left almost the entire state below normal over the past 30 days with most of the state at less than 5 percent of normal (Figure 2b). Most of the state is now in a rainfall deficit over the past 90 days with splotches of normal or above normal rainfall in the eastern half of the state (Figure 2c).

Figure 2a: Inches of precipitation that fell in Texas in the 30 days before October 25, 2020 (source). Note that cooler colors indicate lower values and warmer indicate higher values.

Figure 2b: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the 30 days before October 25, 2020 (source).

Figure 2c: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the 90 days before October 25, 2020 (source).

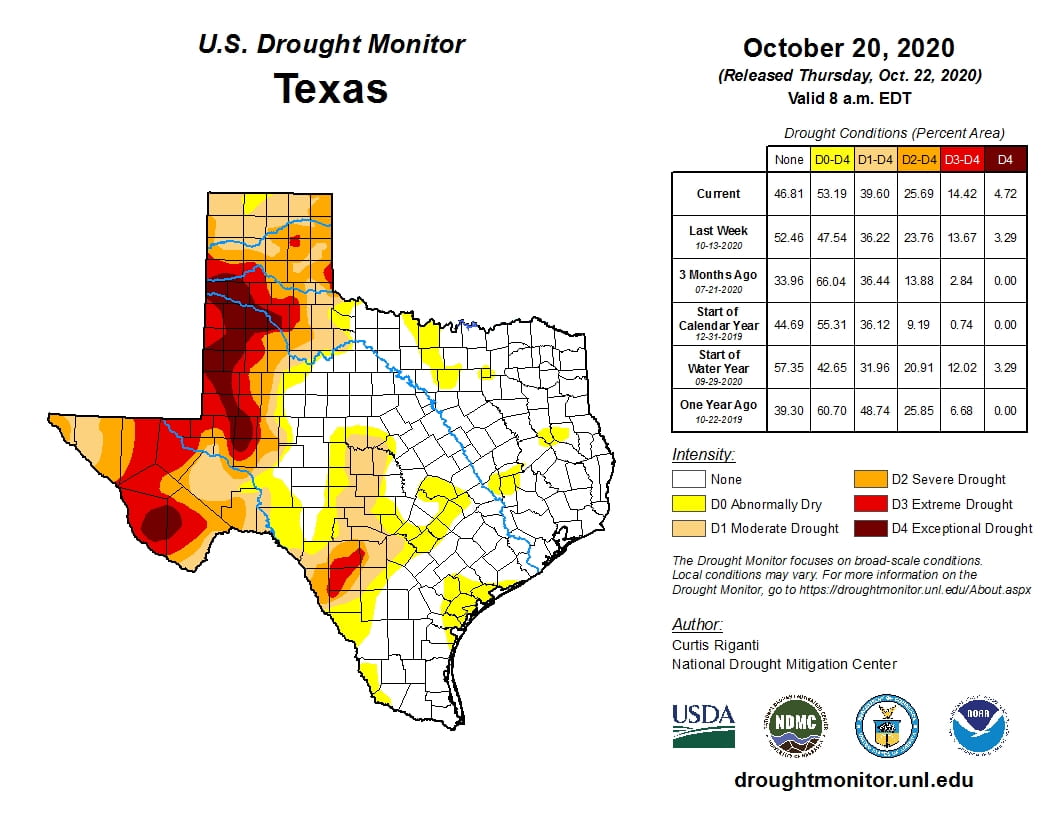

The amount of the state under drought conditions (D1-D4) increased from 31.9 percent four weeks ago to 39.6 percent today (Figure 3a) with a general intensifying of conditions in the High Plains and parts of Far West Texas (Figure 3b). There are two large areas of Exceptional Drought conditions: one with a multi-county (~16) area in the Southern High Plains and a sizable spot in the Big Bend area (Figure 3a). In all, about 53 percent of the state is abnormally dry or worse (D0-D4; Figure 3a), up from 45 percent four weeks ago.

Figure 3a: Drought conditions in Texas according to the U.S. Drought Monitor (as of October 20, 2020; source).

Figure 3b: Changes in the U.S. Drought Monitor for Texas between September 22, 2020 and October 20, 2020 (source).

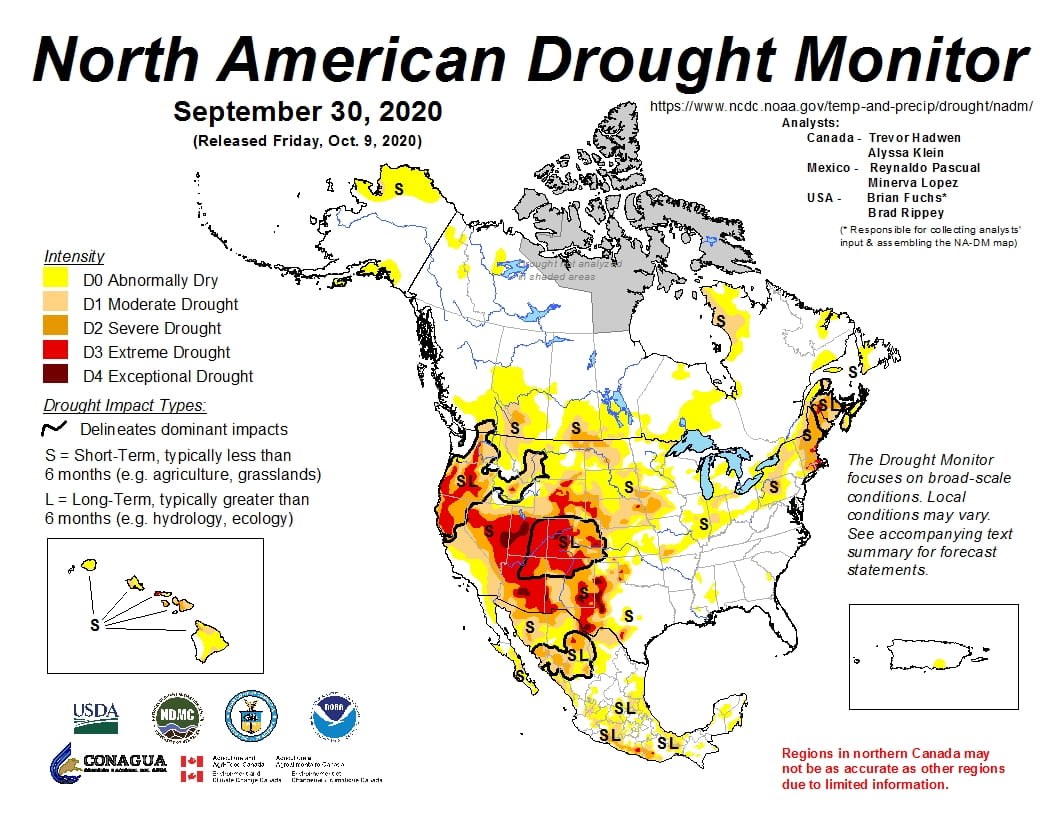

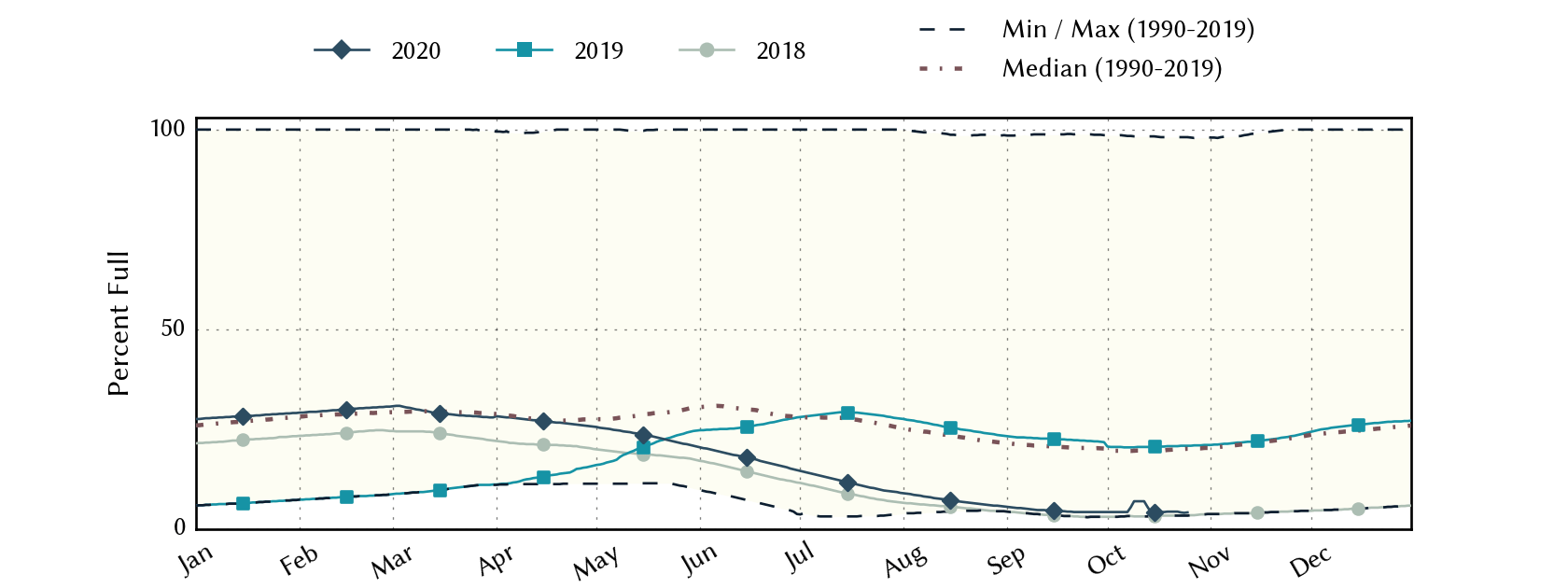

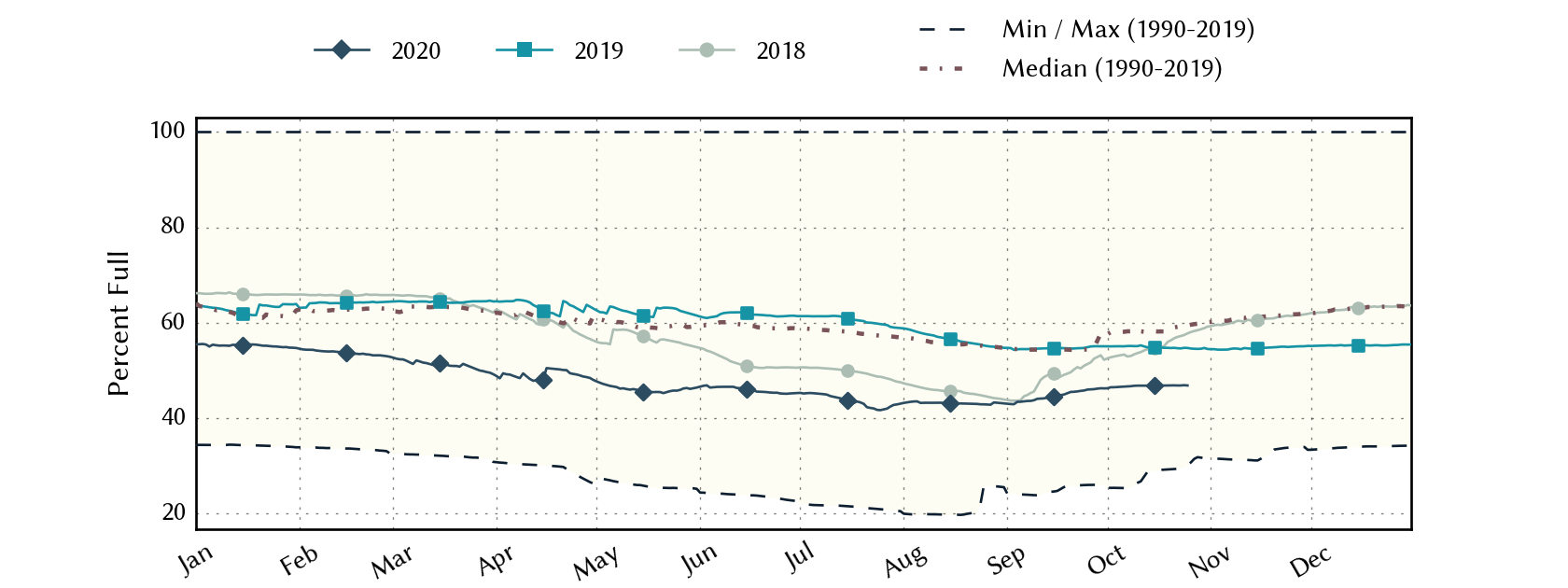

The North American Drought Monitor for September continues to show a large regional drought that stretches from Pacific Northwest down through Texas and deep into Mexico with short-term and long-term effects (Figure 4a). Precipitation in much of the Rio Grande watershed in Colorado and New Mexico over the last 90 days is less than normal with the Sacramento Mountains now at less than 10 percent of normal (Figure 4b). Conservation storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir decreased slightly from 4.2 percent full on September 25 to 4.1 percent on October 25, 2020 (Figure 4c).

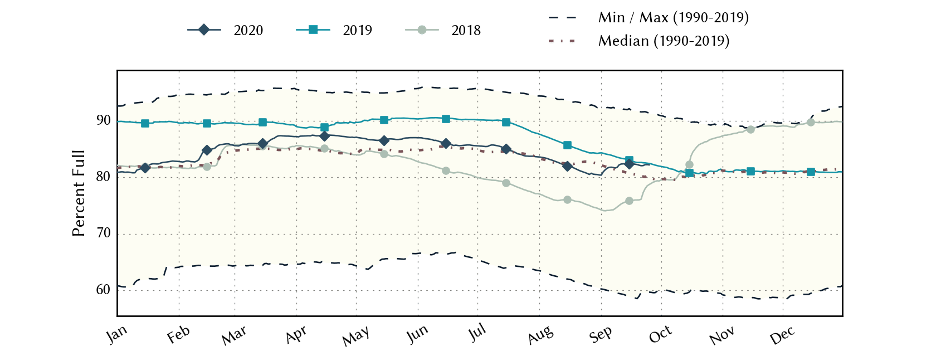

The Rio Conchos basin in Mexico, which confluences into the Rio Grande just above Presidio and is an important source of water to the lower part of the Rio Grande in Texas, continues to show Severe drought but now with a dab of Extreme conditions (Figure 4a). Combined conservation storage in Amistad and Falcon reservoirs increased over the past month from 45.9 percent on September 25 to 46.8 percent on October 25, about 15 percentage points below normal for this time of year (Figure 4d).

Figure 4a: The North American Drought Monitor for September 30, 2020 (source).

Figure 4b: Percent of normal precipitation for Colorado and New Mexico for the 90 days before October 20, 2020 (source). The red line is the Rio Grande Basin. I use this map to see check precipitation trends in the headwaters of the Rio Grande in southern Colorado, the main source of water to Elephant Butte Reservoir downstream.

Figure 4c: Reservoir storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir since 2018 with the median, min and max for measurements since 1990 (source).

Figure 4d: Reservoir storage in Amistad and Falcon reservoirs since 2018 with the median, min and max for measurements since 1990 (source).

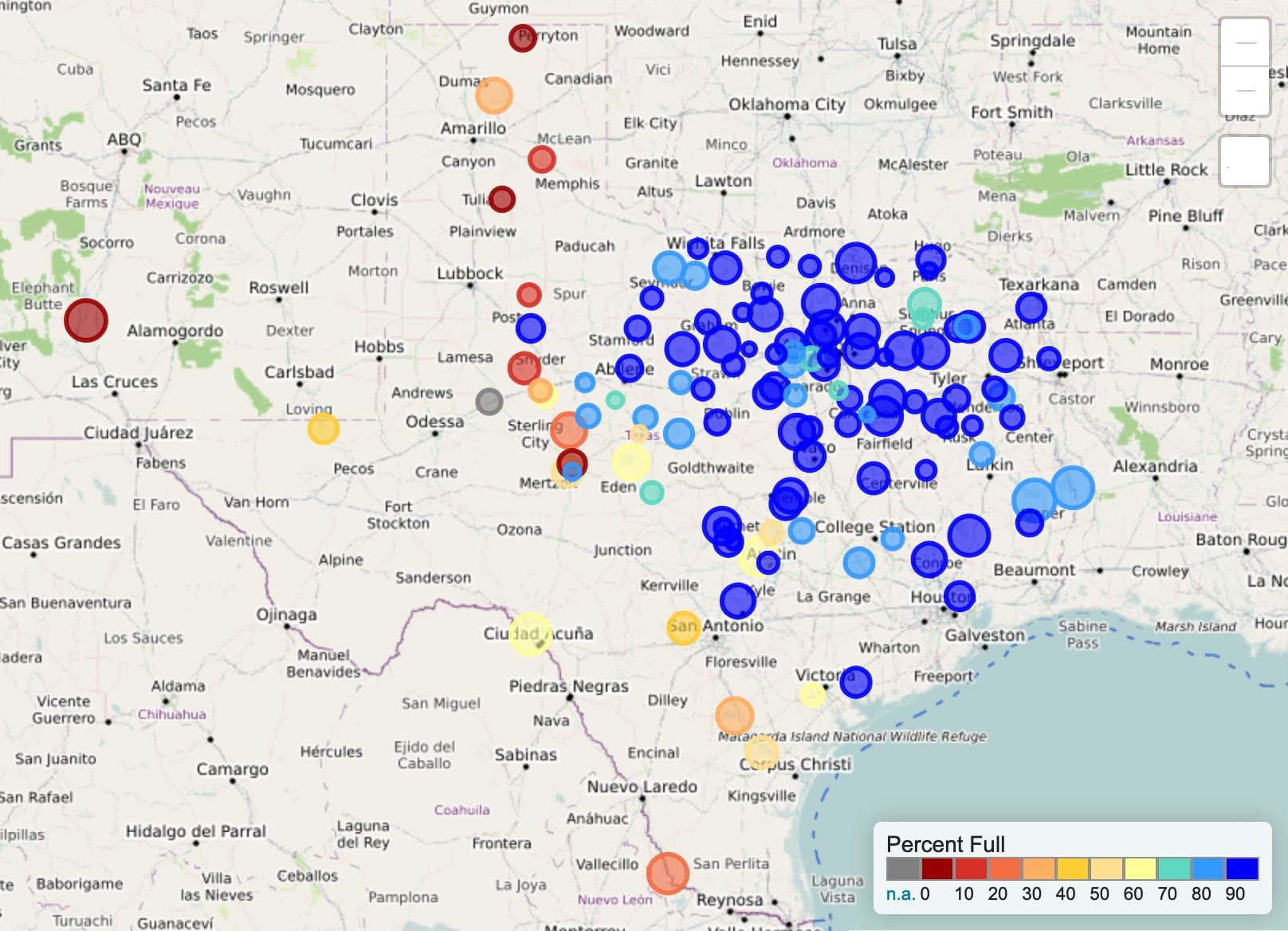

A number of river/stream basins in the state have flows over the past seven days that are less than 25 percent of normal with about a dozen catchments with flows less than 10 percent of normal and six less than 5 percent of normal (Figure 5a). Statewide reservoir storage is at 80.2 percent full as of October 25, down from 82.2 percent a month ago and about a percentage point below normal for this time of year (Figure 5b). Storage in individual reservoirs decreased from last month with some reservoirs falling back below 90 percent full (Figure 5c).

Figure 5a: Parts of the state with below-normal seven-day average streamflow as of October 25, 2020 (source).

Figure 5b: Statewide reservoir storage since 2018 compared to statistics (median, min and max) for statewide storage since 1990 (source).

Figure 5c: Reservoir storage as October 20, 2020 in the major reservoirs of the state (source).

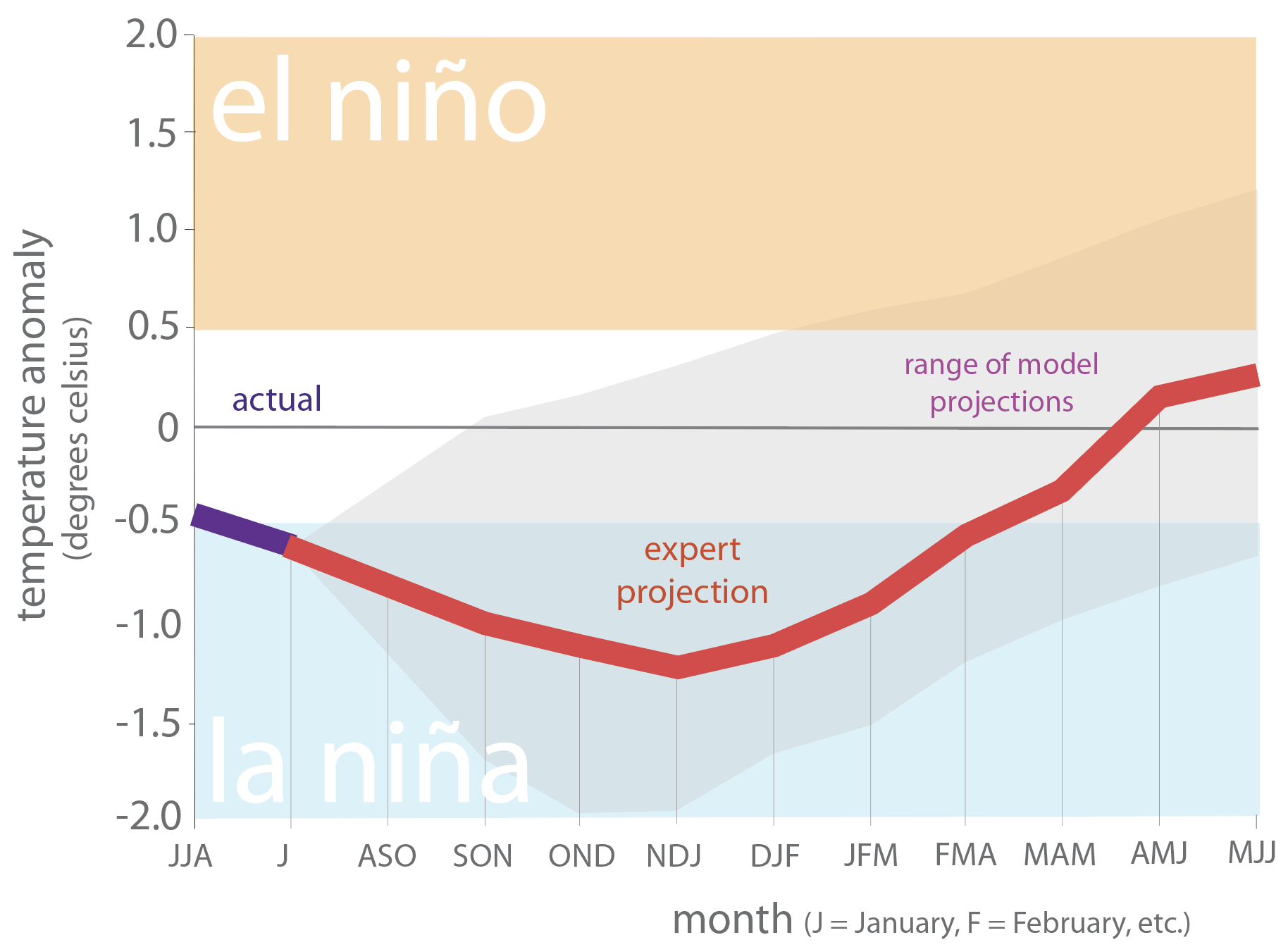

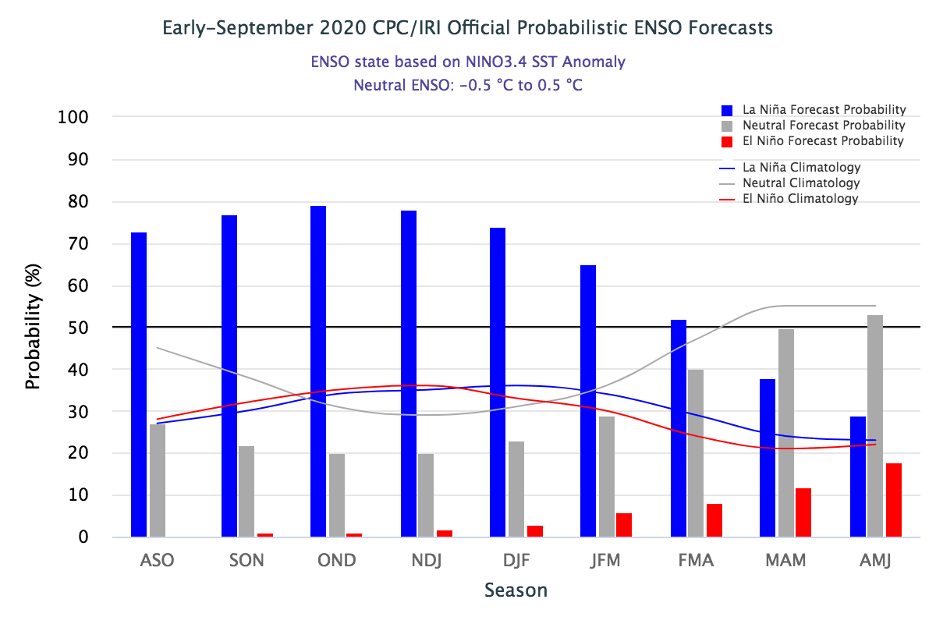

Sea-surface temperatures in the Central Pacific entered La Niña conditions in August and are expected to continue their cooling trend (Figure 6a). The Climate Prediction Center increased the chance of La Niña conditions continuing through the winter from ~75 percent last month to ~85 percent this month with a ~60 percent chance of continuing through the spring (Figure 6b).

Figure 6a. Forecasts of sea-surface temperature anomalies for the Niño 3.4 Region as of September 18, 2020 (modified from source).

Figure 6b. Probabilistic forecasts of El Niño, La Niña and La Nada conditions (source).

The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook through January 31, 2021 projects drought persistence and development in almost all of Texas (Figure 7a). The three-month temperature outlook projects warmer-than-normal conditions statewide with greater warming to the west (Figure 7b) while the three-month precipitation slightly favors drier-than-normal conditions for the state (Figure 7c).

Figure 7a: The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook for October 15, 2020, through January 31, 2021 (source).

Figure 7b: Three-month temperature outlook from October 15, 2020 (source).

Figure 7c: Three-month precipitation outlook from October 15, 2020 (source).

Author

Robert Mace

Executive Director & Chief Water Policy Officer at The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment

Robert Mace is the Executive Director and the Chief Water Policy Officer at the Meadows Center. He is also Professor of Practice in the Department of Geography at Texas State University. Robert has over 30 years of experience in hydrology, hydrogeology, stakeholder processes, and water policy, mostly in Texas.