SUMMARY:

- Texas continues to remain mostly in drought with 93 percent of the state at least abnormally dry.

- There’s a 50 percent chance of La Niña transitioning to neutral conditions by April–June.

- There may be patchy fog on Christmas Eve at the North Pole.

I wrote this article on December 20, 2020.

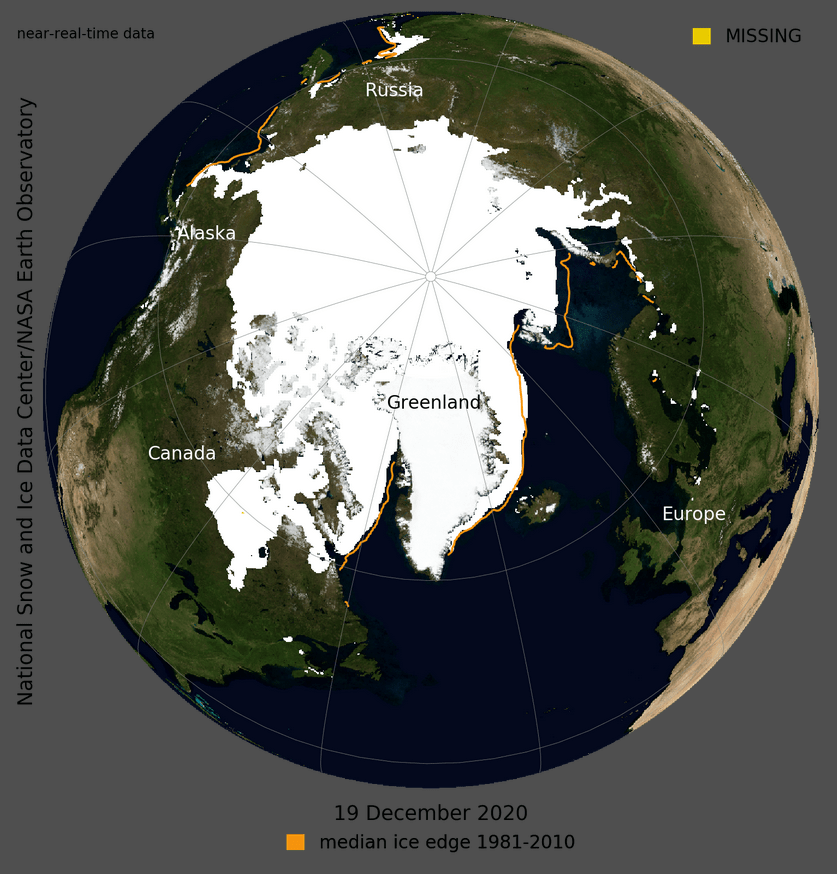

Given the season, let’s a take quick look at what Santa’s dealing with at the North Pole. Despite surface air temperatures for the past 12 months being the second warmest on record, daily sea ice for December 20 (and projections through the end of the year) looks good (Santa, Mrs. Santa and the elves ain’t swimming just yet; Figure 1a). Storminess (an actual technical term) has increased over the past several decades due to warming, but Santa built his house out of brick, so his operation—for the time being—is pretty resilient.

Melt ponds during recent summer months have required Santa to elevate his structures and buy flood insurance, something Mrs. Claus isn’t too happy with, although it is easier to water the reindeer these days. Mr. and Mrs. Claus are currently in the market for a used drilling platform since scientists project that the ice at the pole will be melted by 2050, at least during the summer months.

As of December 20, the temperature was -27 degrees Fahrenheit with 65% humidity and winds at 8 miles per hour. The weather station says the winds are from the northwest, but I don’t know what the heck that means at the North Pole because there ain’t no more north north of the North Pole. The temperature for Christmas Eve is projected to be -24 degrees Fahrenheit with winds of 6 miles per hour and a 10% chance of precipitation. Patchy fog will require Rudolph’s services during takeoffs and landings. Longer term, the North Atlantic Oscillation, aka “Santa’s El Niño”, is in a neutral phase trending cool, which generally means cooler temperatures for the eastern United States.

Figure 1: Daily sea ice index for December 20, 2020 (source).

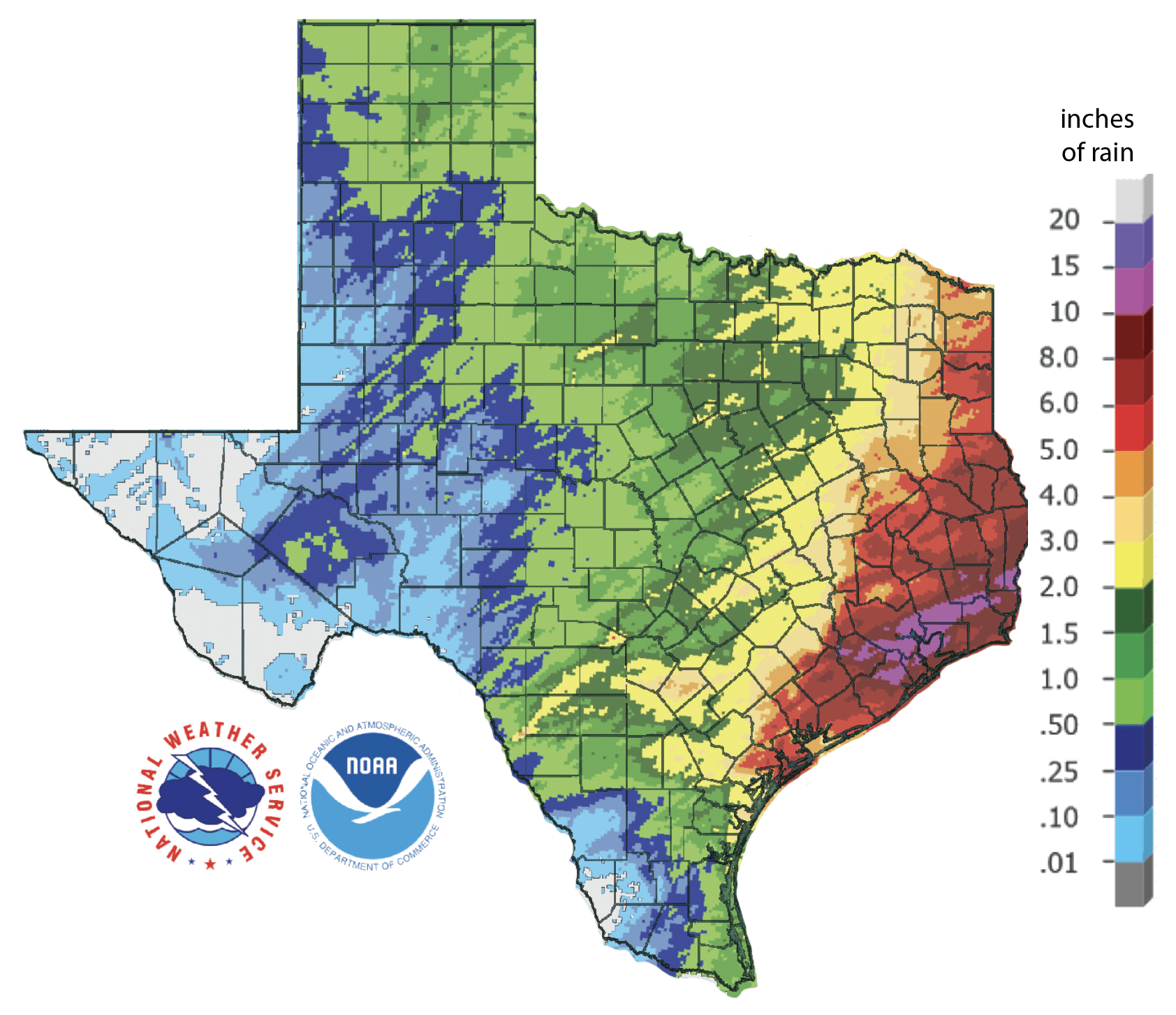

Parts of Southeast Texas received more than 10 inches of rain over the past 30 days with North-Central and Central Texas benefitting from 1 to 2 inches of precipitation (including some arriving frozen to the north!) (Figure 2a). However, much of West and Far West Texas and a large part of the Lower Rio Grande Valley received less than a quarter inch with large areas getting nothing (Figure 2a).

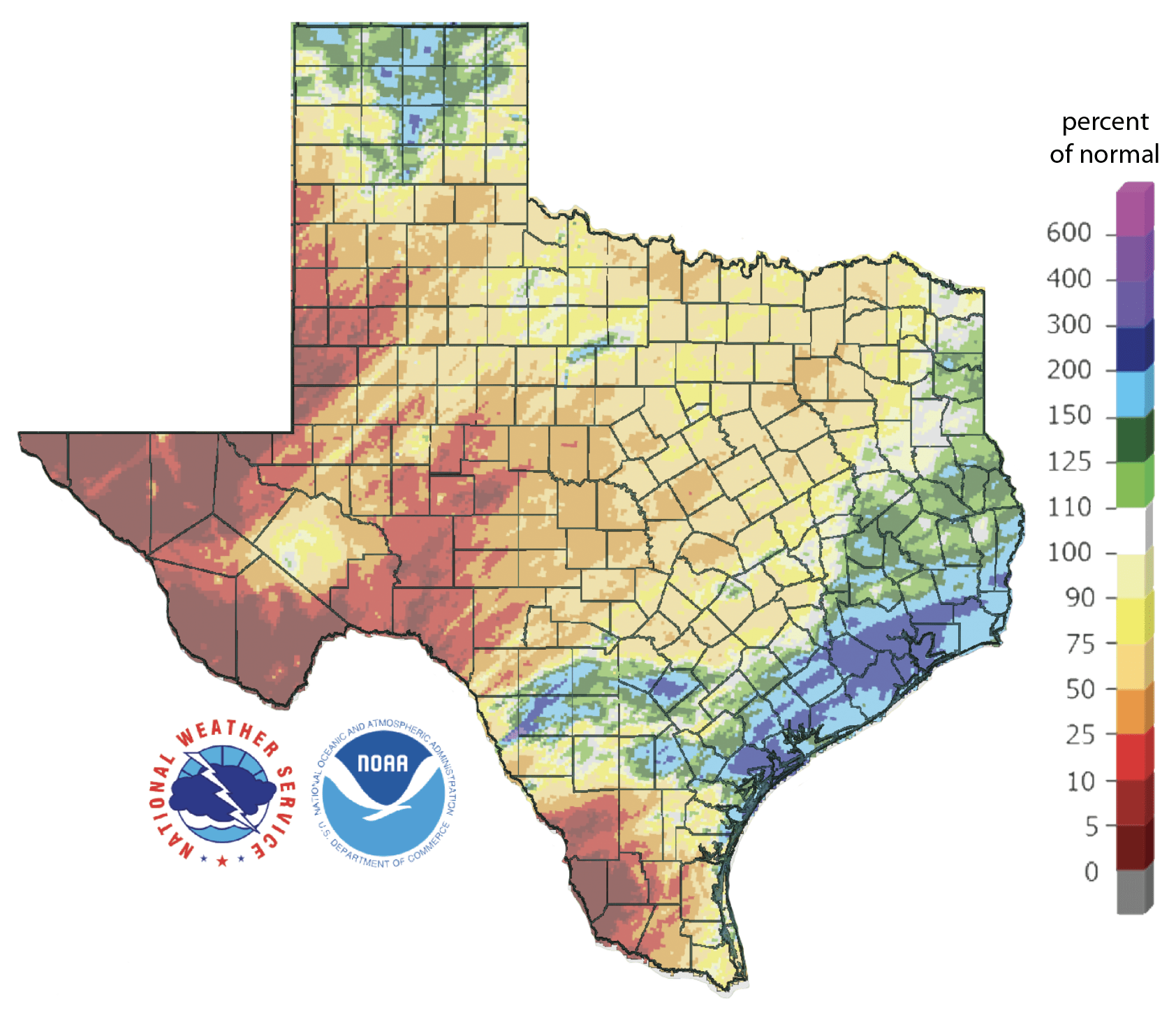

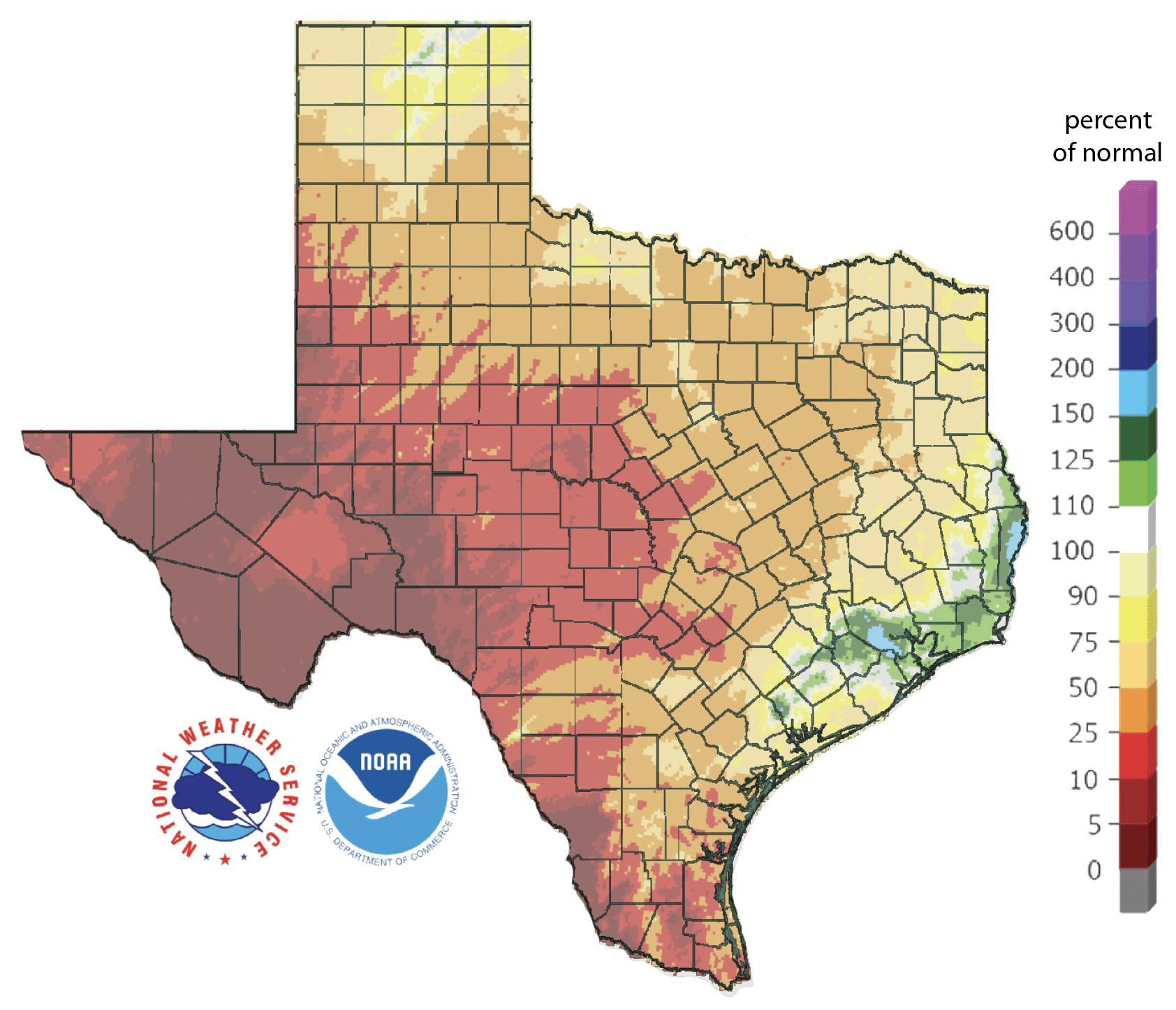

With the exception of the northern Gulf Coast, the High Plains north of Amarillo and blotches of South Texas, the rest of the state received less-than-normal rainfall over the past 30 days with the aforementioned West and Far West Texas and the Lower Rio Grande Valley receiving less than 5% to 10% of normal rainfall (Figure 2b). Most of the state is now in a rainfall deficit over the past 90 days with a small splotch of normal in the Houston-to-Beaumont area and a whisper of normal in the High Plains near Oklahoma (Figure 2c).

Figure 2a: Inches of precipitation that fell in Texas in the 30 days before December 20, 2020 (source). Note that cooler colors indicate lower values and warmer indicate higher values.

Figure 2b: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the 30 days before December 20, 2020 (source).

Figure 2c: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the 90 days before December 20, 2020 (source).

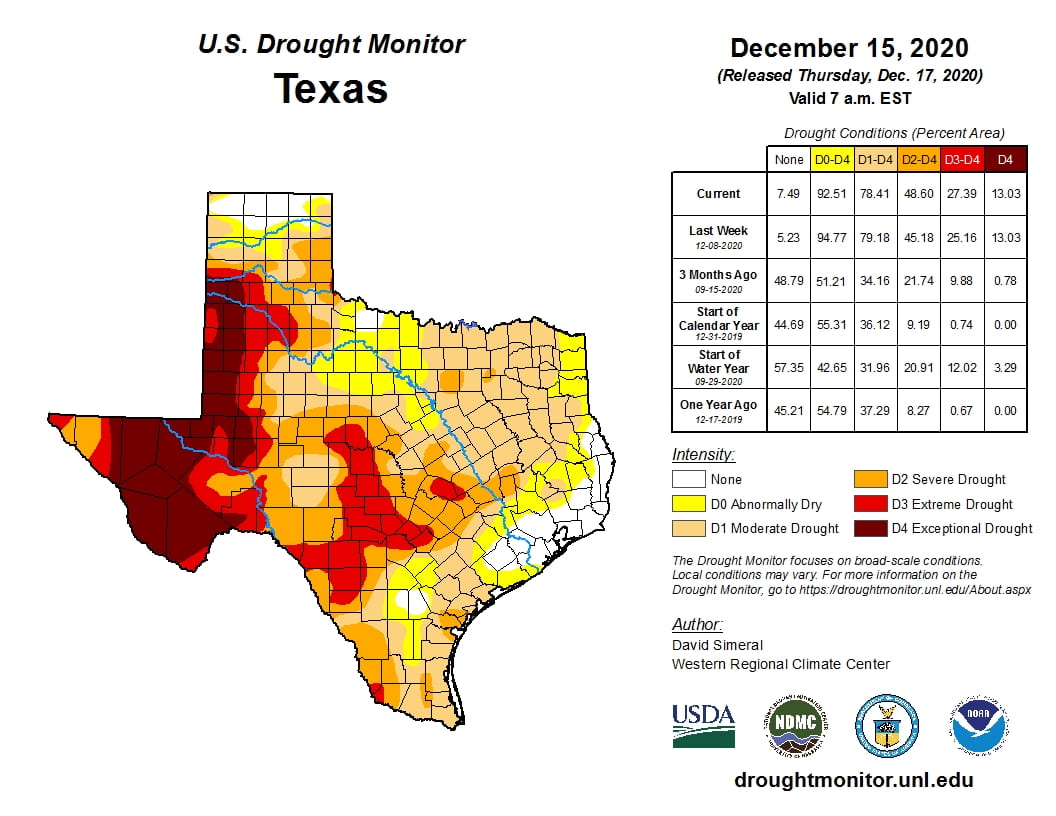

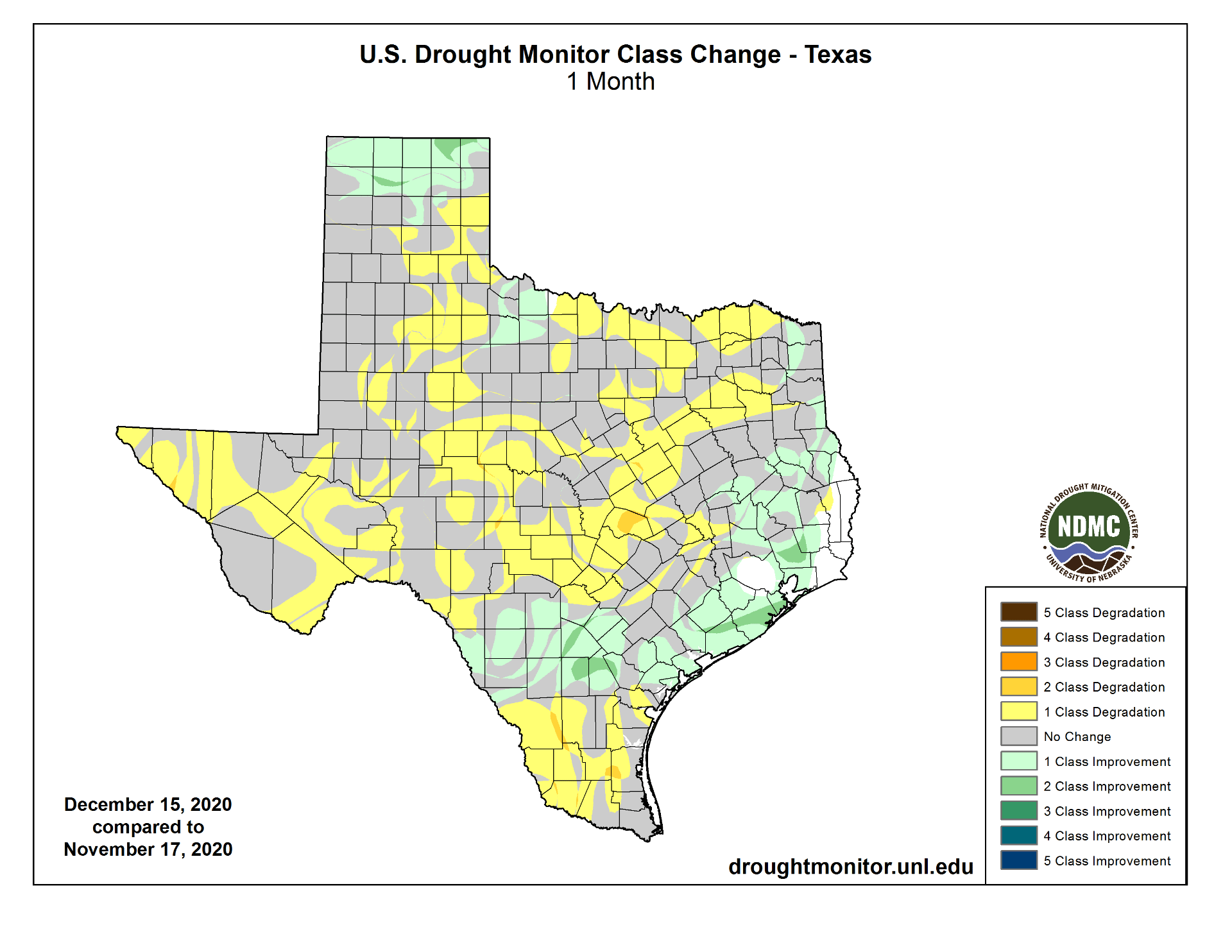

The amount of the state under drought conditions (D1–D4) increased from 75.4% four weeks ago to 78.4% as of December 15 (Figure 3a) with a general intensifying of conditions across the state except in the High Plains and the upper Gulf Coast, where drought eased (Figure 3b).

Exceptional Drought—focused in West and Far West Texas—increased from 9.1% to 13% of the state while Extreme Drought increased from 20.5% to 27.4% of the state. In all, 92.5% of the state is abnormally dry or worse (D0–D4; Figure 3a), down from 97.2% four weeks ago.

Figure 3a: Drought conditions in Texas according to the U.S. Drought Monitor (as of December 15, 2020; source).

Figure 3b: Changes in the U.S. Drought Monitor for Texas between November 17, 2020, and December 15, 2020 (source).

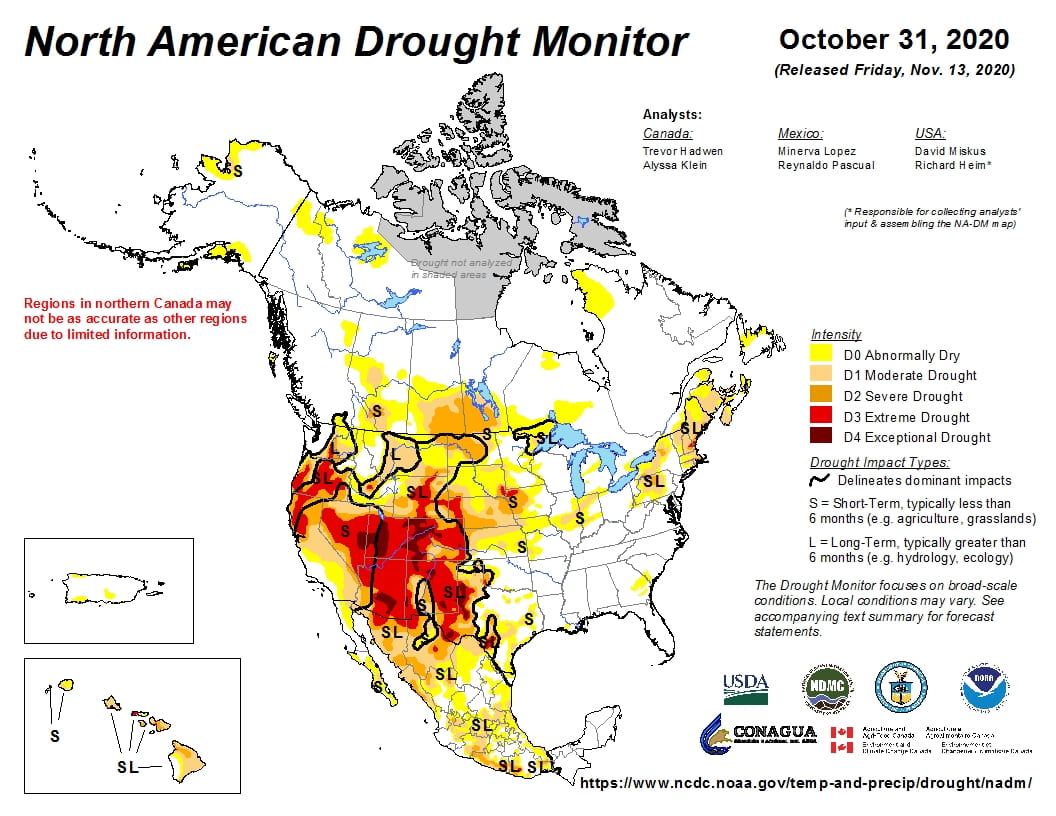

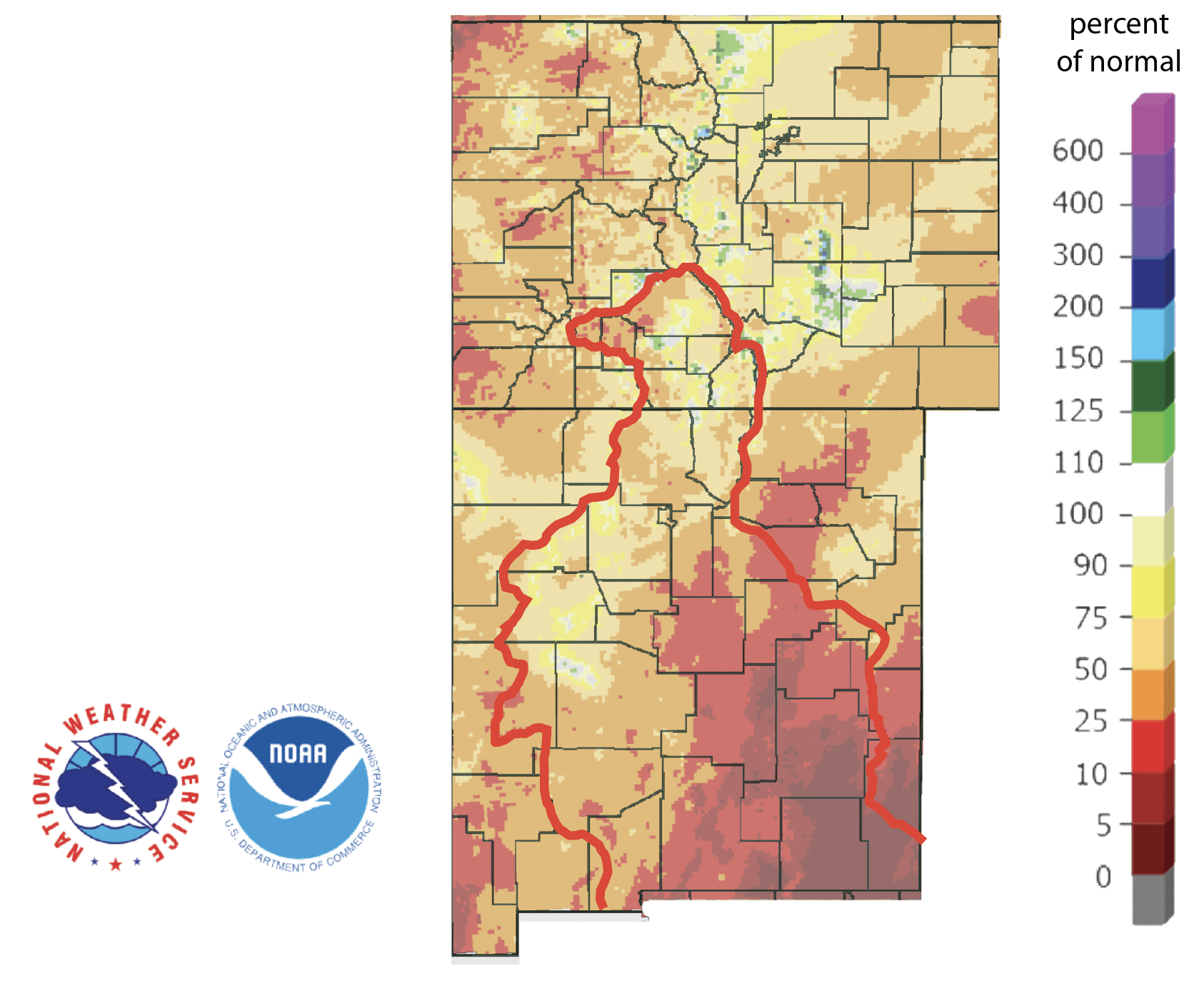

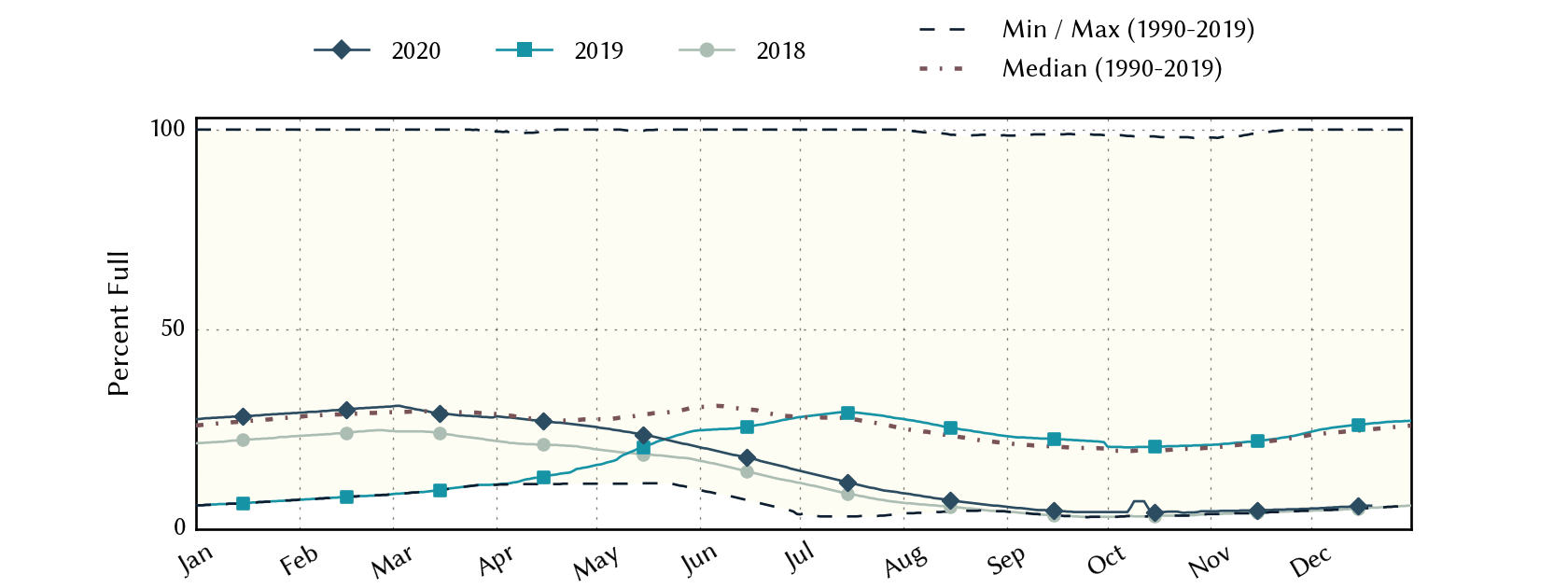

The North American Drought Monitor for October continues to show a large regional drought that stretches from Pacific Northwest down through Texas and into Mexico with short-term and long-term effects (Figure 4a). Precipitation in almost all of the Rio Grande watershed in Colorado and New Mexico over the last 90 days is less than normal with the Sacramento Mountains remaining at less than 5 percent of normal (Figure 4b). Conservation storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir increased slightly from 5% full on November 25 to 5.8% on December 20 (Figure 4c), near historic lows.

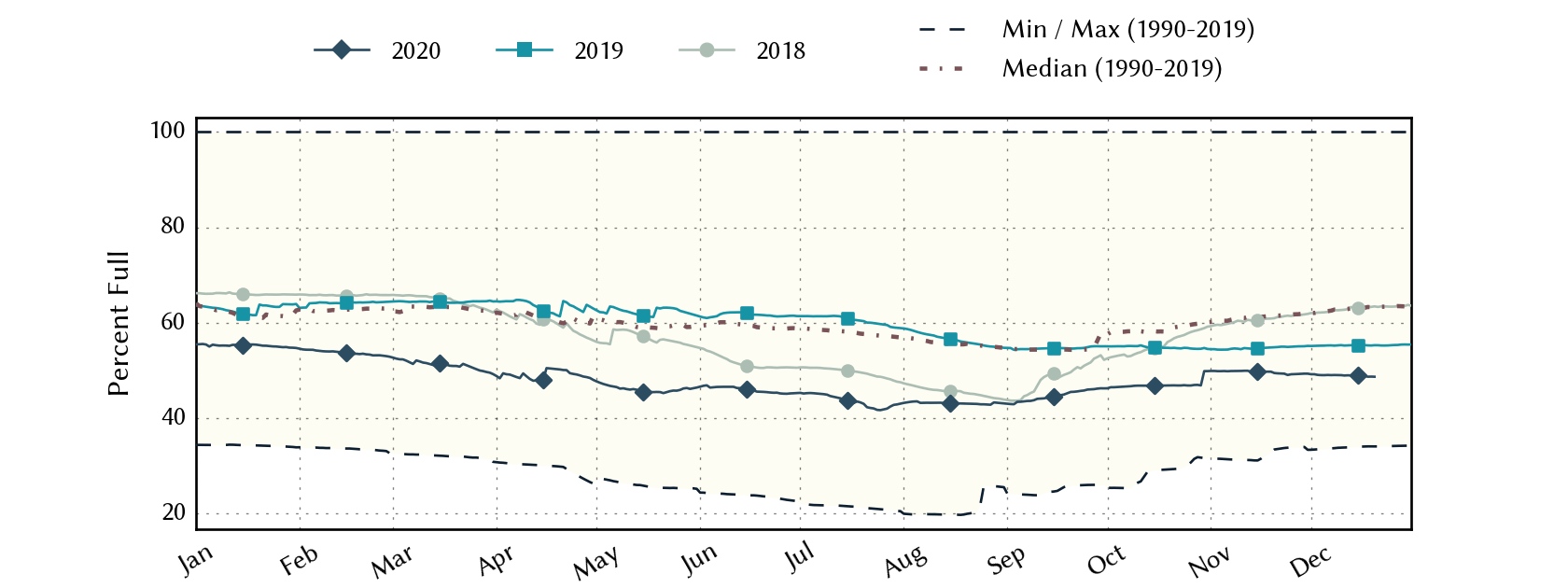

The Rio Conchos basin in Mexico, which confluences into the Rio Grande just above Presidio and is an important source of water to the lower part of the Rio Grande in Texas, continues to show Severe drought with a dab of Extreme conditions (Figure 4a). Combined conservation storage in Amistad and Falcon reservoirs decreased over the past month from 49.3% on November 29 to 48.7% on December 20, about 17 percentage points below normal for this time of year (Figure 4d).

Figure 4a: The North American Drought Monitor for October 31, 2020 (source).

Figure 4b: Percent of normal precipitation for Colorado and New Mexico for the 90 days before December 20, 2020 (source). The red line is the Rio Grande Basin. I use this map to see check precipitation trends in the headwaters of the Rio Grande in southern Colorado, the main source of water to Elephant Butte Reservoir downstream.

Figure 4c: Reservoir storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir since 2018 with the median, min and max for measurements since 1990 (source).

Figure 4d: Reservoir storage in Amistad and Falcon reservoirs since 2018 with the median, min and max for measurements since 1990 (source).

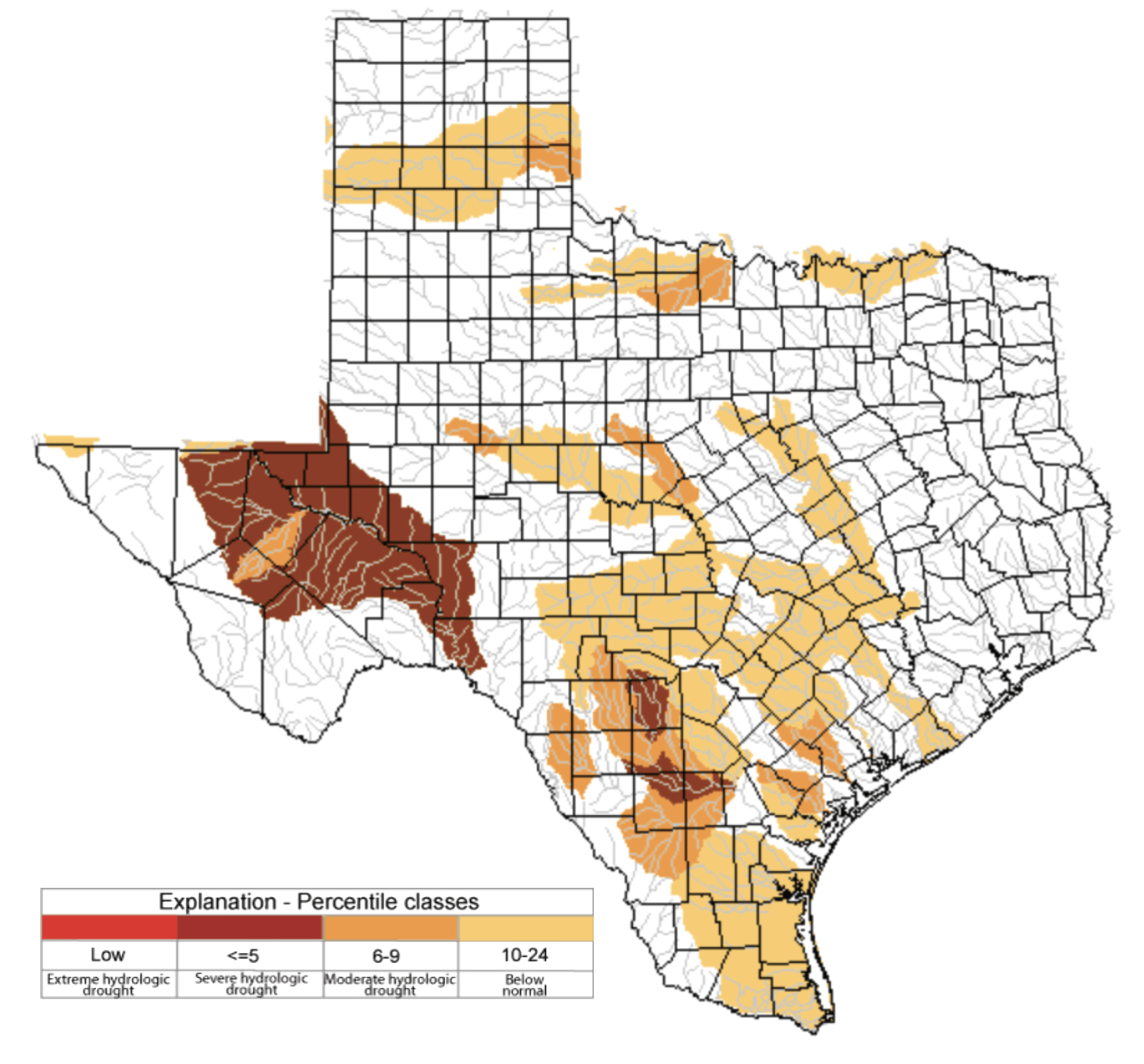

A number of river/stream basins in the state have flows over the past seven days that are less than 25 percent of normal with several catchments in severe hydrologic drought with flows less than 5 percent of normal (Figure 5a).

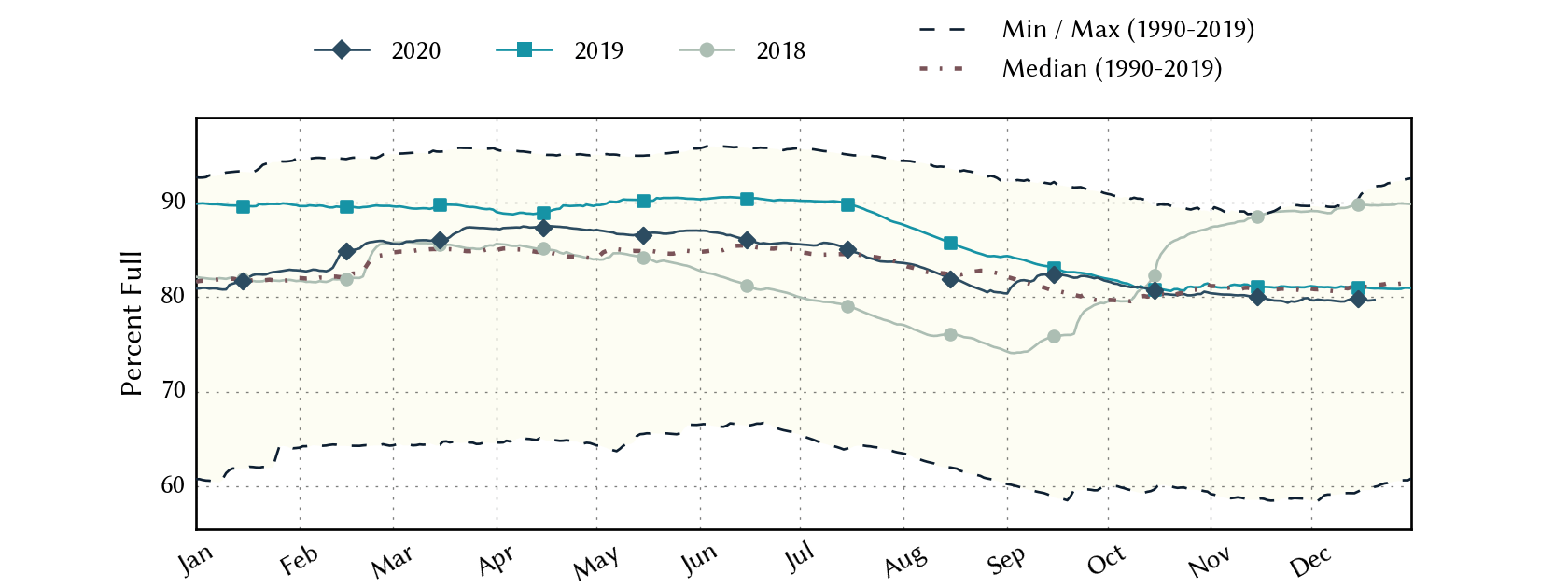

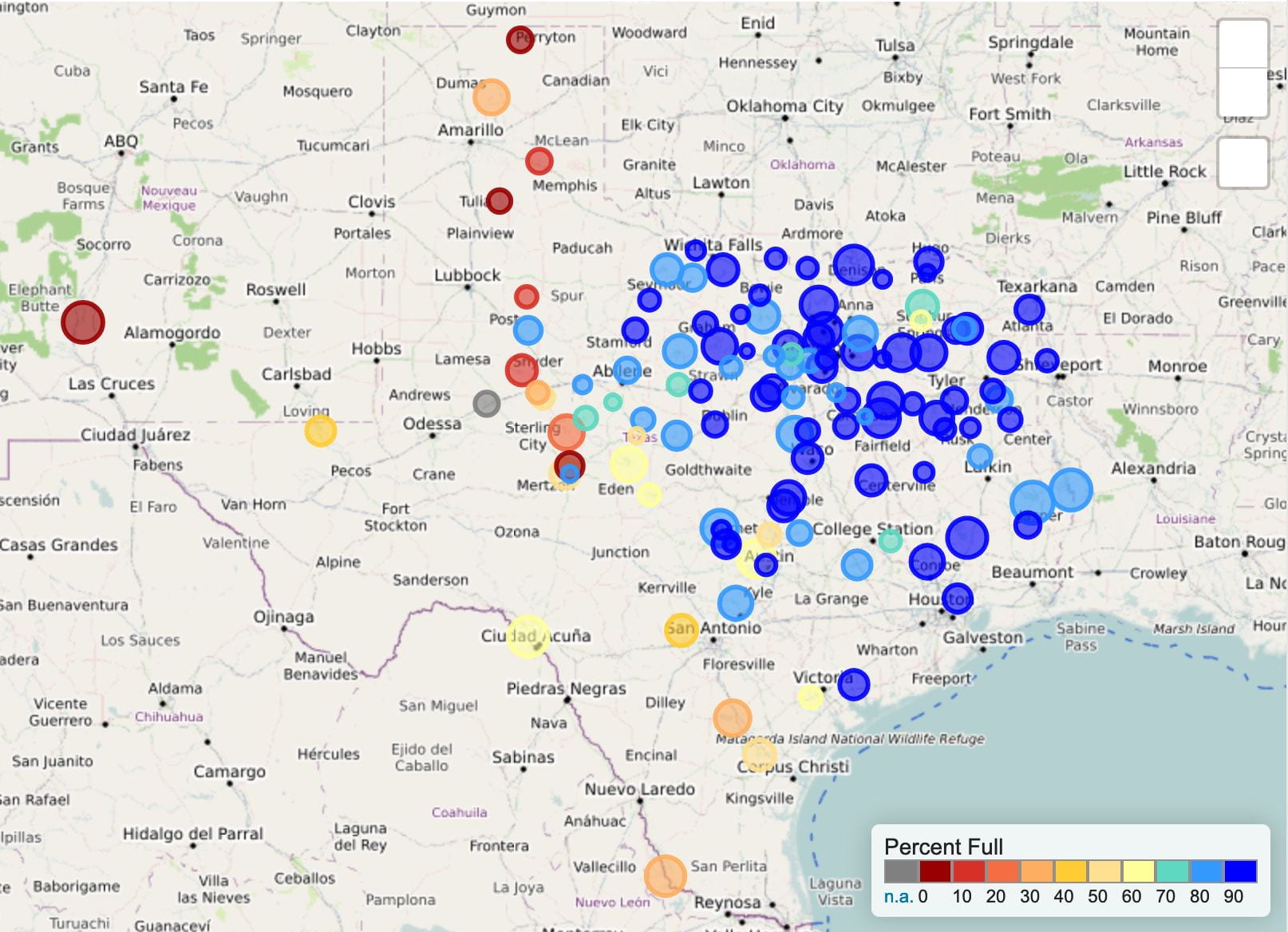

Statewide reservoir storage is at 79.7% full as of November 29, down slightly from 79.8% a month ago, and about a percentage point below normal for this time of year (Figure 5b). Storage in individual reservoirs decreased from last month with Cooper [Chapman] Lake and Gibbons Creek Reservoir falling below 80% full, Lake Sulphur Springs and Lake Travis falling below 70% full (Figure 5c) and Lake Georgetown below 60% full (Figure 5c).

Figure 5a: Parts of the state with below-normal seven-day average streamflow as of December 20, 2020 (source).

Figure 5b: Statewide reservoir storage since 2018 compared to statistics (median, min and max) for statewide storage since 1990 (source).

Figure 5c: Reservoir storage as December 20, 2020 in the major reservoirs of the state (source).

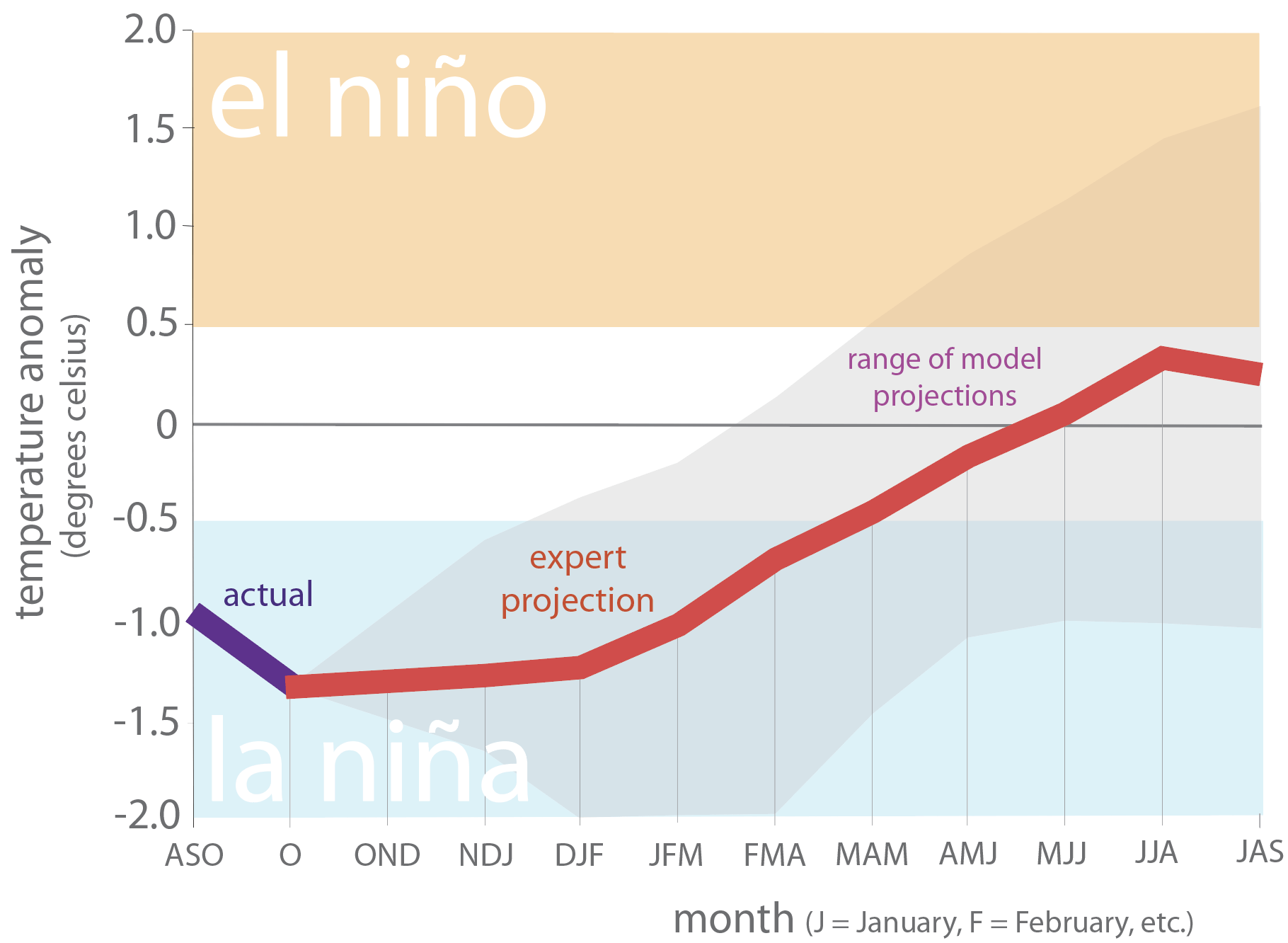

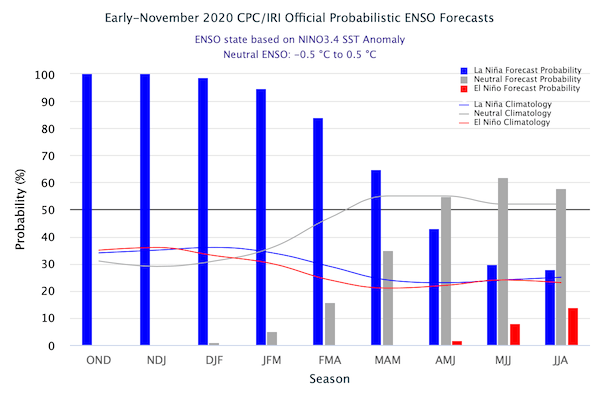

Sea-surface temperatures in the Central Pacific entered La Niña conditions in August and have continued their cooling trend as projected (Figure 6a). The Climate Prediction Center maintained the chance of La Niña conditions continuing through the winter (through March) at ~95% with a ~50% chance of neutral conditions projected for April through June (Figure 6b).

Figure 6a. Forecasts of sea-surface temperature anomalies for the Niño 3.4 Region as of October 19, 2020 (modified from source).

Figure 6b. Probabilistic forecasts of El Niño, La Niña and La Nada conditions (source).

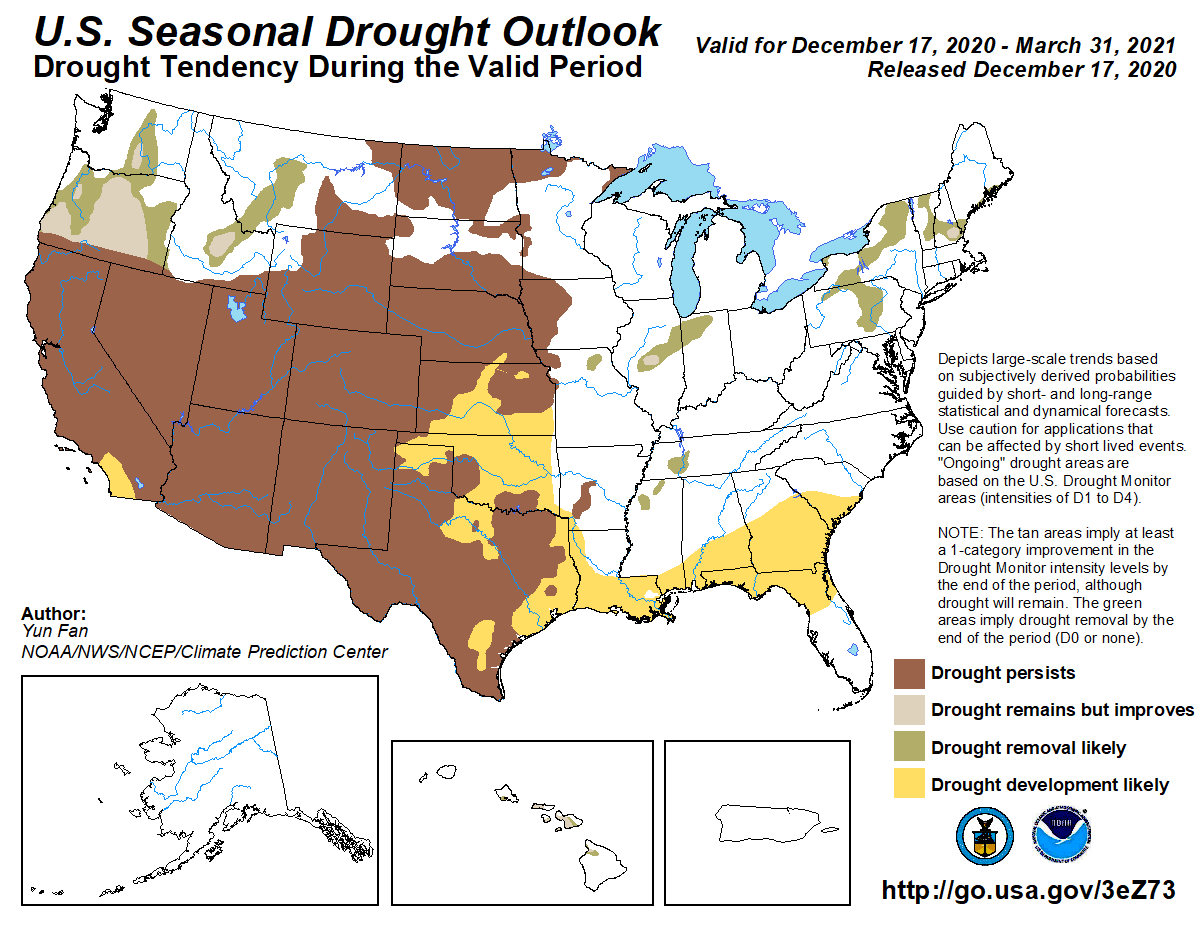

The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook through March 31, 2021 projects drought persistence and development in all of Texas (Figure 7a). The three-month temperature outlook projects warmer-than-normal conditions statewide with greater warming to the southwest (Figure 7b) while the three-month precipitation slightly favors drier-than-normal conditions for the state with drier conditions in West and Far West Texas (Figure 7c).

Figure 7a: The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook for December 17, 2020, through March 2021 (source).

Figure 7b: Three-month temperature outlook from December 17, 2020 (source).

Figure 7c: Three-month precipitation outlook from December 17, 2020 (source).

Author

Robert Mace

Executive Director & Chief Water Policy Officer at The Meadows Center for Water and the Environment

Robert Mace is the Executive Director and the Chief Water Policy Officer at The Meadows Center. He is also Professor of Practice in the Department of Geography at Texas State University. Robert has over 30 years of experience in hydrology, hydrogeology, stakeholder processes and water policy, mostly in Texas.