SUMMARY:

- 29% of the state is in Exceptional drought, the worst drought category

- La Niña conditions are getting stronger with the fall and early winter favoring a continued La Niña advisory

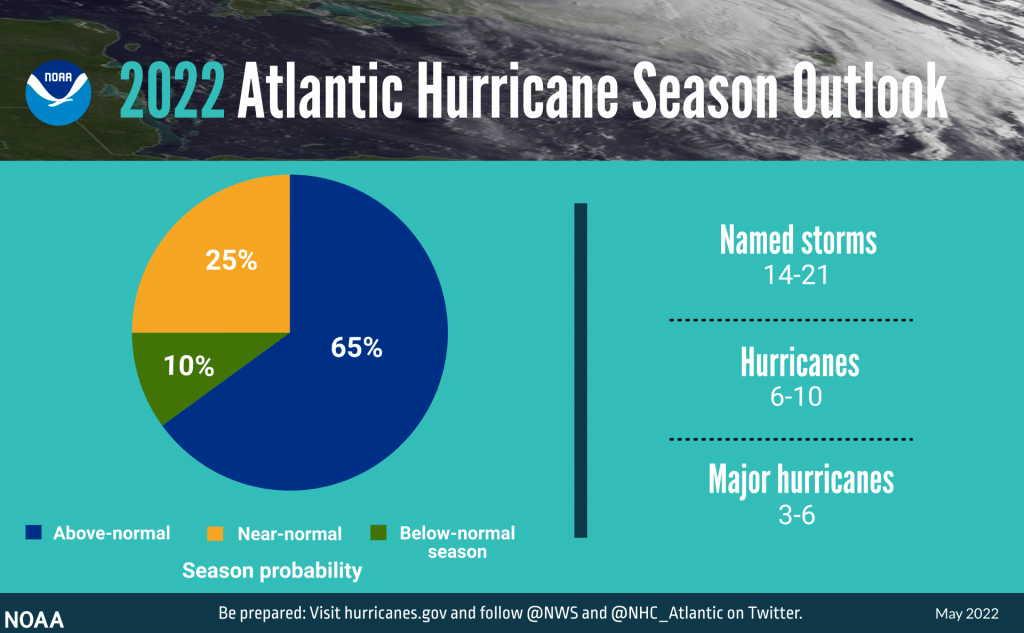

- The Climate Prediction Center projects 14 to 21 named storms, of which 6 to 10 might become hurricanes

I wrote this article on May 25, 2022.

Last month I showed Colorado State University’s projections for the 2022 hurricane season — this month I’ll discuss the Climate Prediction Center’s projections. The Climate Prediction Center, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, favors an active hurricane season with a 65% chance of an above-normal season. They think (with 70% confidence) that there will be 14 to 21 named storms, of which 6 to 10 might become hurricanes and 3 to 6 of those might become major hurricanes. Colorado State University projected 19 named tropical storms, 9 hurricanes, and 4 major hurricanes.

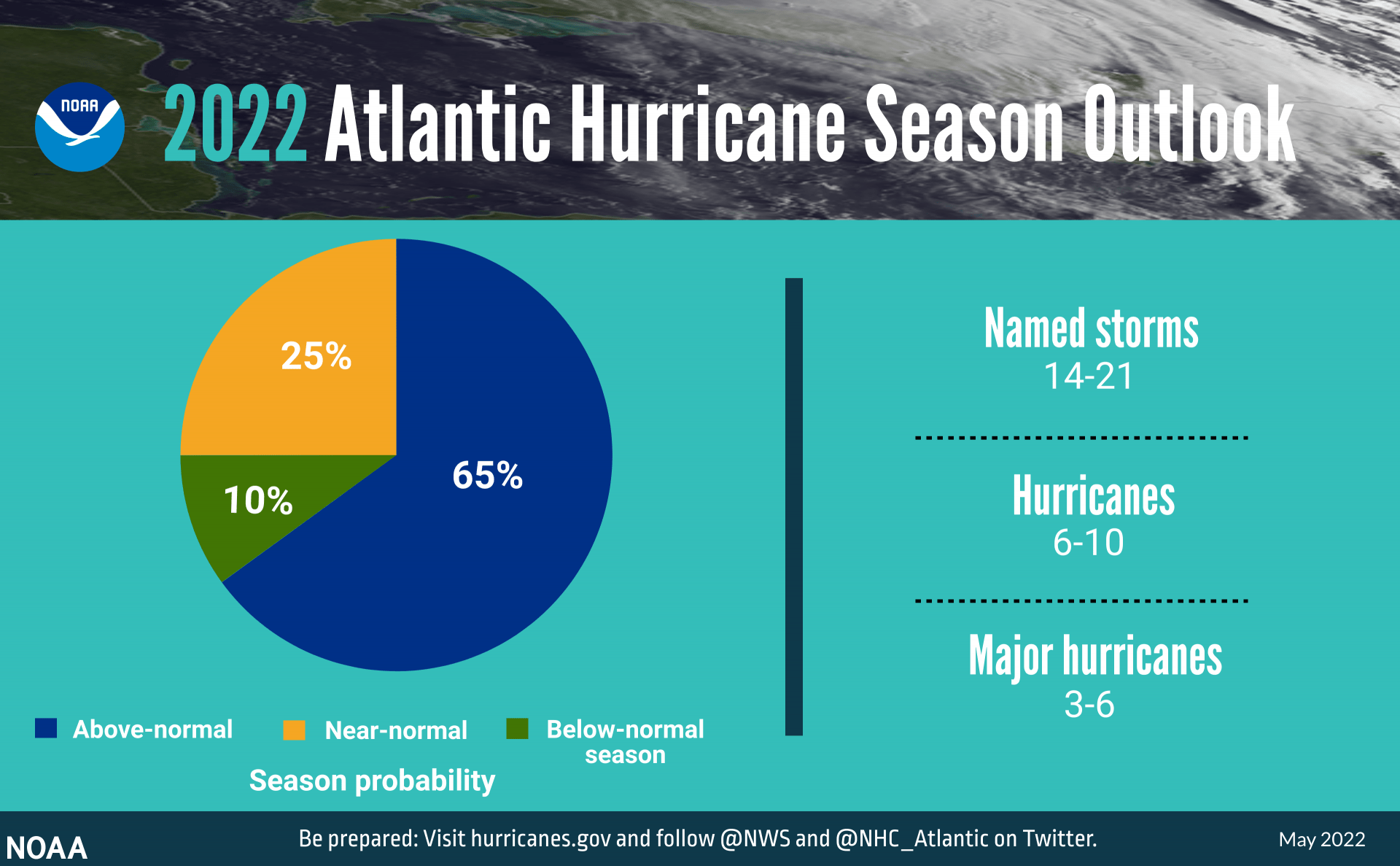

The Center’s projections are informed in part by La Niña conditions (which suppress tropical-storm-killing windshear in the Atlantic), warmer-than-normal sea-surface temperatures in the Atlantic and Caribbean (a source of energy to tropical storms), weaker tropical Atlantic trade winds (less windshear), and an active west African monsoon season (storm seeds). Names for the storms include Earl, Hermine, Paula, and Walter (Figure 1b). Unlike Colorado State University’s projections, the Center does not project landfalls (although, to be accurate, Colorado State University only opines on a storm reaching within 50 miles of coast). The Center will revisit its projections in early August. Hurricane season runs from June 1 through November 30.

Figure 1a: The Climate Prediction Center’s projections for the 2022 hurricane season (source).

Figure 1b: Names for the 2022 hurricane season (source).

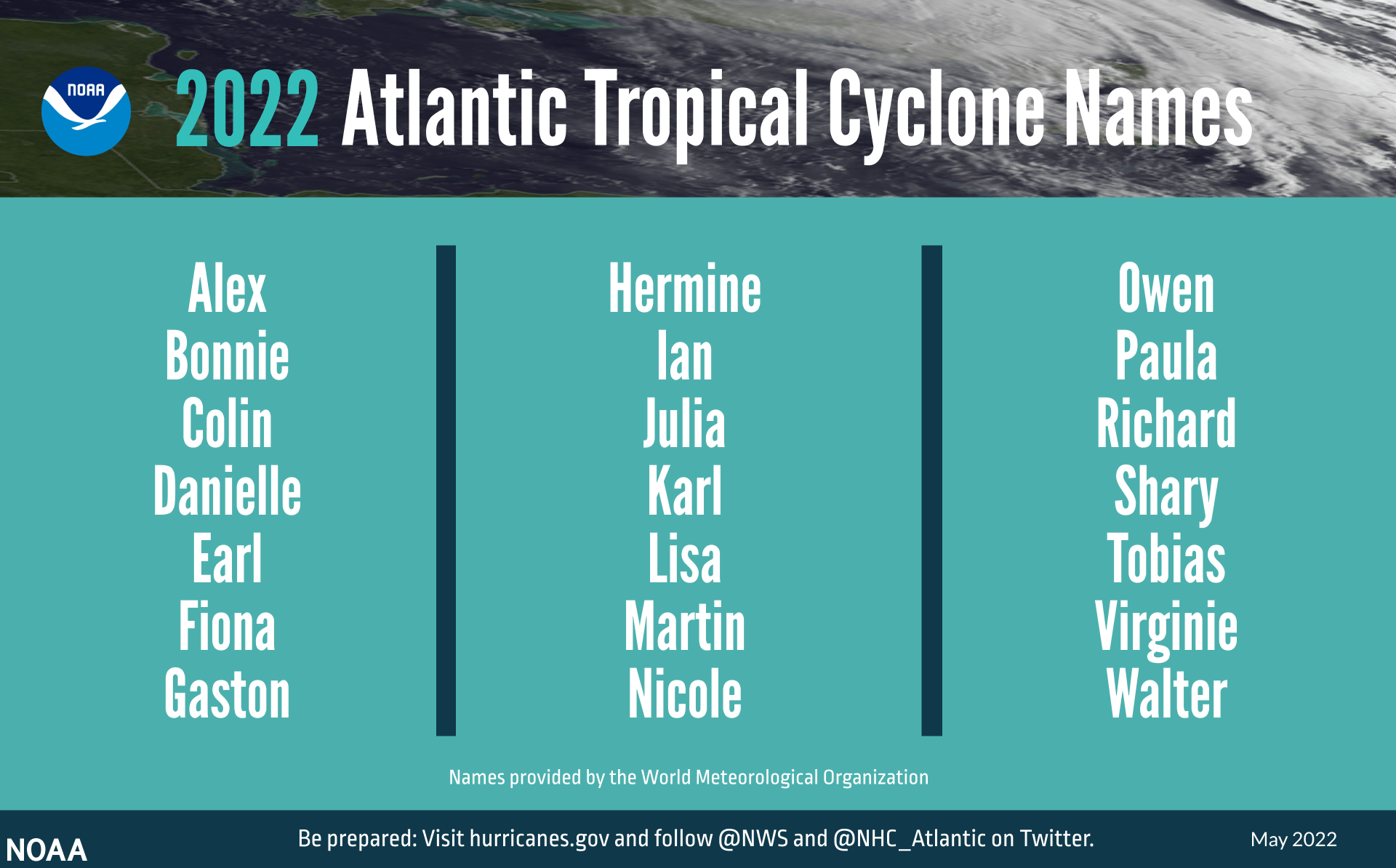

Over the past 30 days, we’ve seen an uptick in rainfall compared to earlier months with the usual wetter-in-the-east-and-drier-in-the-west pattern but with good rains in the Lower Rio Grande Valley (Figure 2a). Regardless of the welcome uptick in rains, much of state remains drier than normal over the past 30 days (Figure 2b). Rain over the past 90 days — a big driver for drought conditions — remains below normal for almost the entire state except for parts of northeastern Texas and the Lower Rio Grande Valley (Figure 2c).

Figure 2a: Inches of precipitation that fell in Texas in the 30 days before May 25, 2022 (modified from source). Note that cooler colors indicate lower values and warmer indicate higher values. Light grey is no detectable precipitation.

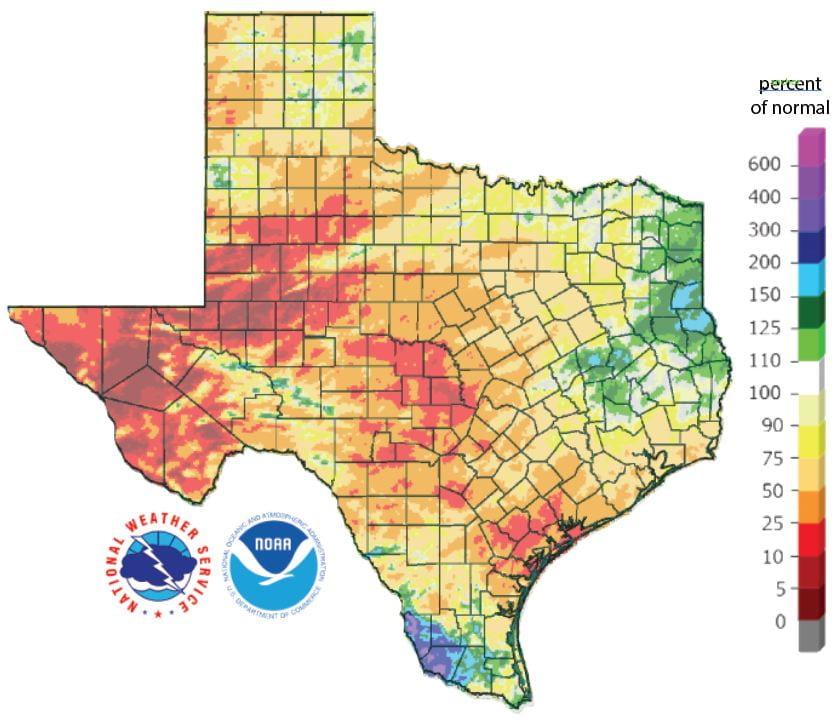

Figure 2b: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the 30 days before May 24, 2022 (modified from source).

Figure 2c: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the 90 days before May 24, 2022 (modified from source).

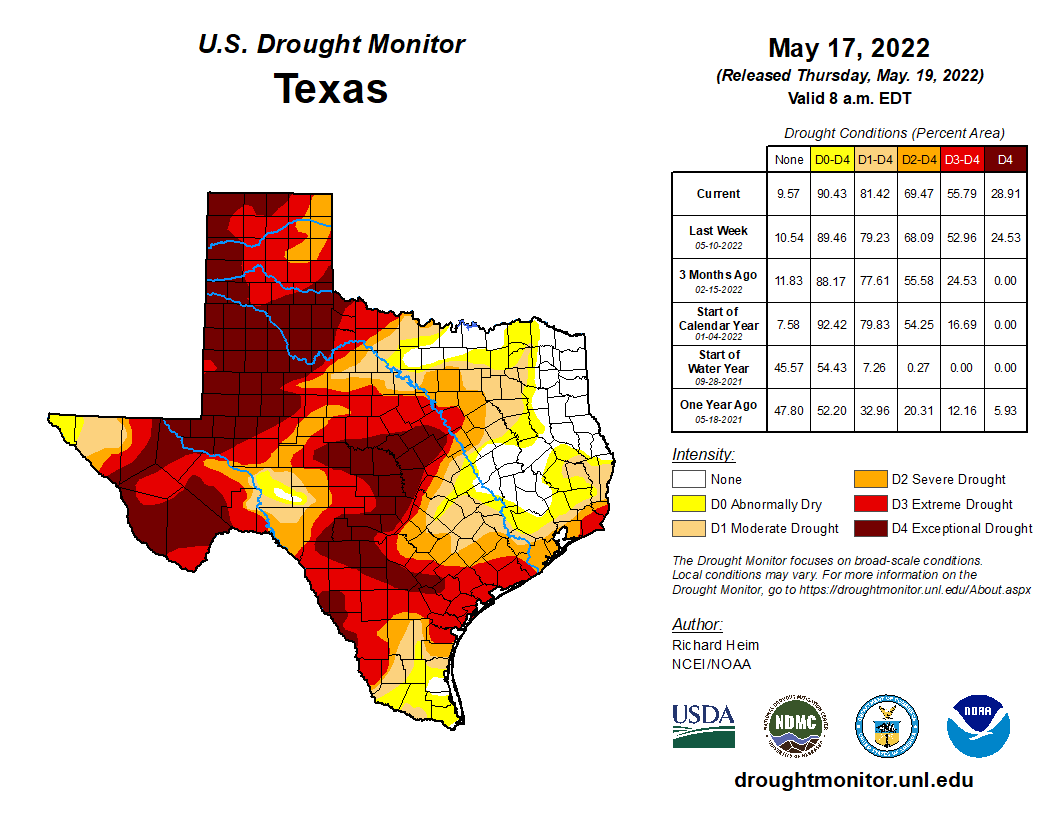

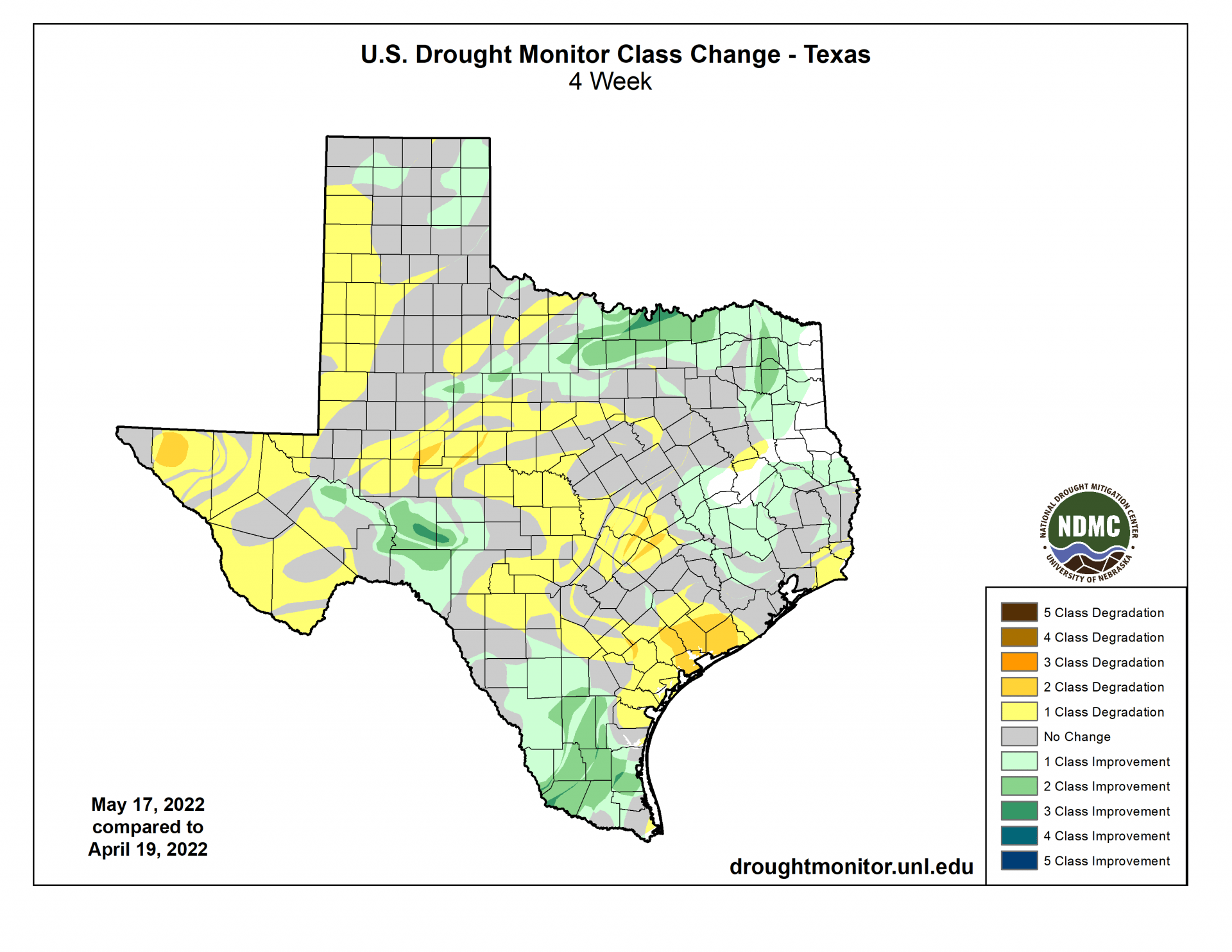

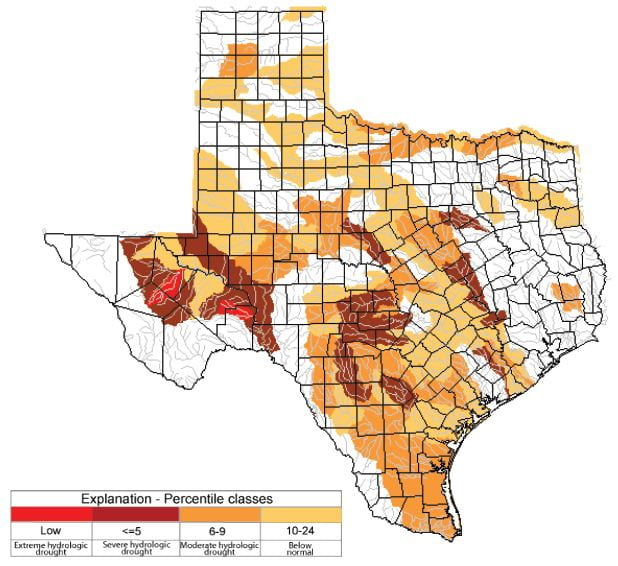

The amount of the state under drought conditions (D1–D4) decreased from 87.7% four weeks ago to 81.4% today (Figure 3a) with drought retreating or ameliorating across the state but also expanding and deepening across the state (Figure 3b). Extreme drought or worse has increased to about 56% of the state with exceptional drought doubling in coverage to 29% of the state (Figure 3a). In all, 90.4% of the state remains abnormally dry or worse (D0–D4; Figure 3a), up from 97% five weeks ago.

Figure 3a: Drought conditions in Texas according to the U.S. Drought Monitor (as of May 17, 2022; source).

Figure 3b: Changes in the U.S. Drought Monitor for Texas between April 19, 2022, and May 17, 2022 (source).

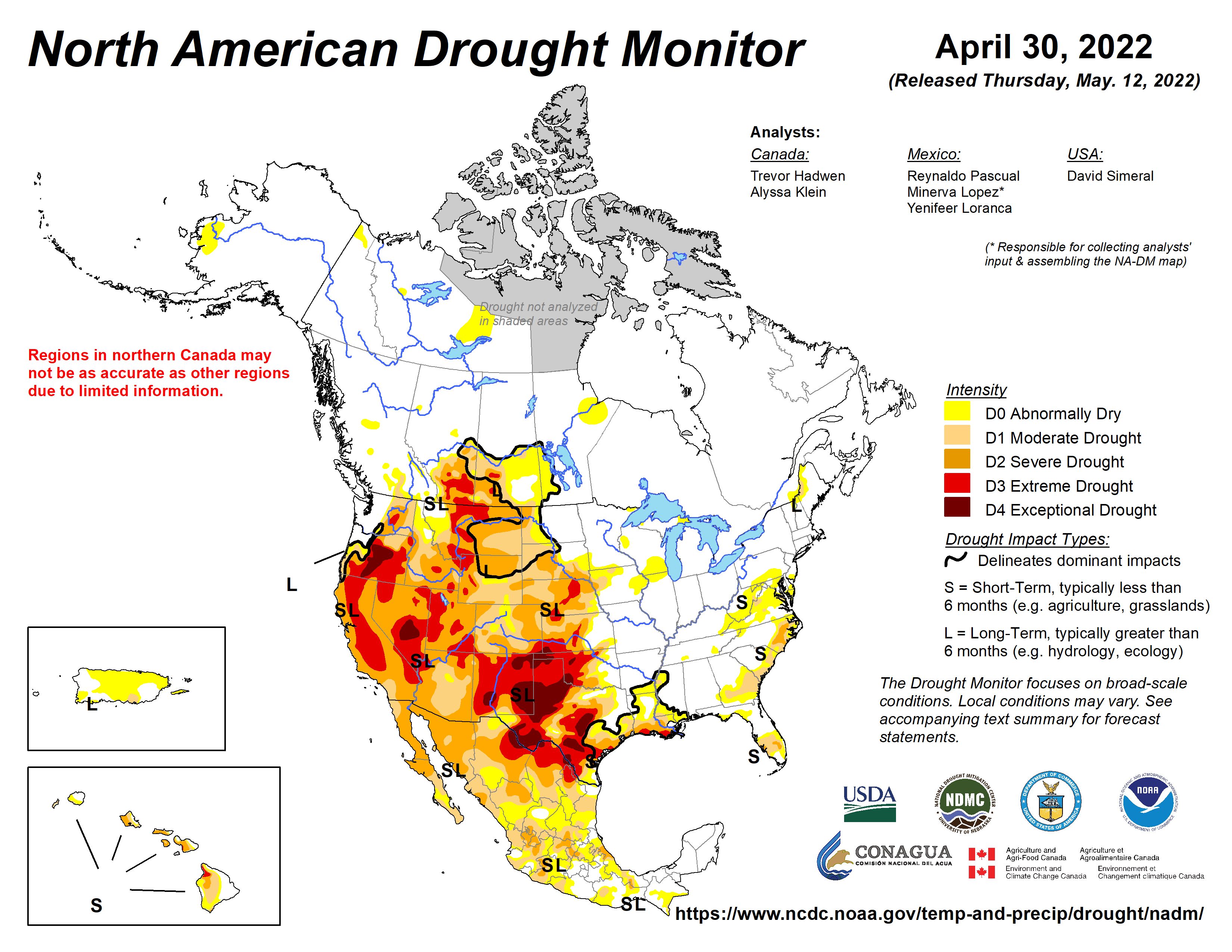

The North American Drought Monitor, which runs a month behind, continues to show drought over much of the western United States with Texas looking like the center of the drought in terms of current severity (Figure 4a). Precipitation in the vast majority of the Rio Grande watershed in Colorado and New Mexico over the last 90 days was less than normal, although the watershed in Colorado did see some major precipitation (Figure 4b). You can also see how bad the rainfall deficit is in New Mexico in general, a factor affecting historic forest fires in the state (Figure 4b).

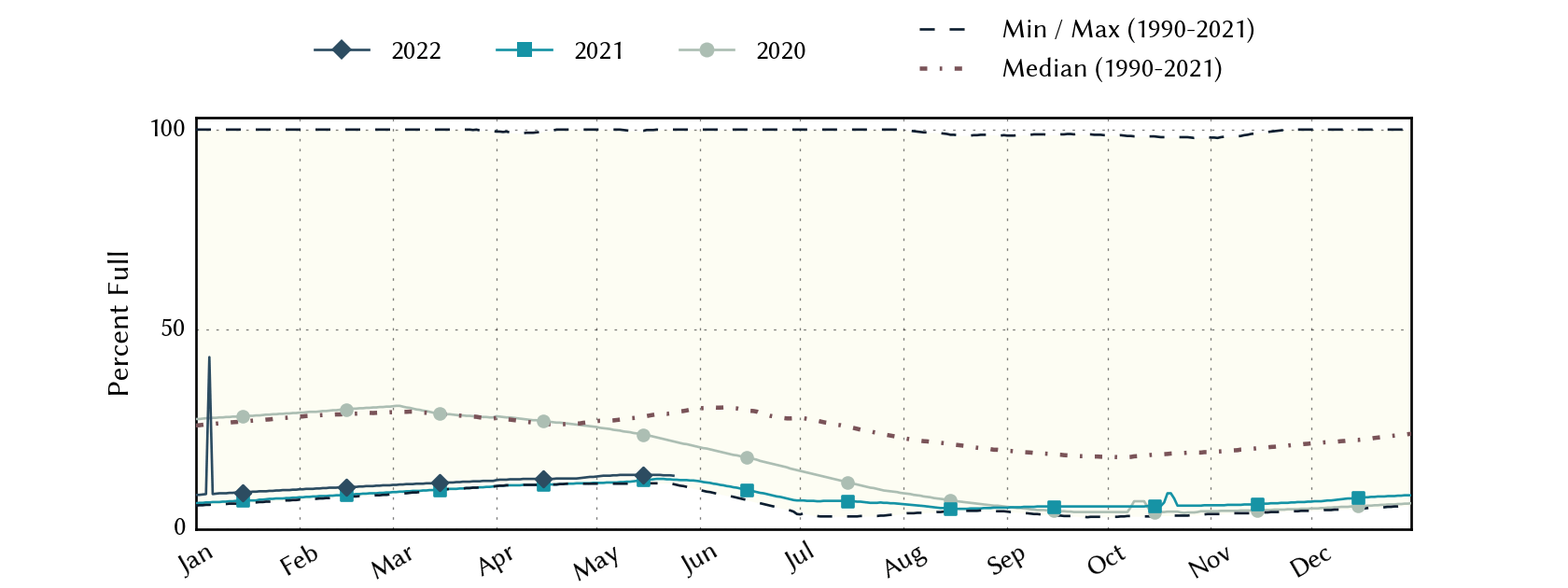

Conservation storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir — an important source of water for the El Paso area — increased from 12.5% full last month to 13.3% today (Figure 4c), just above historic (since 1990) lows.

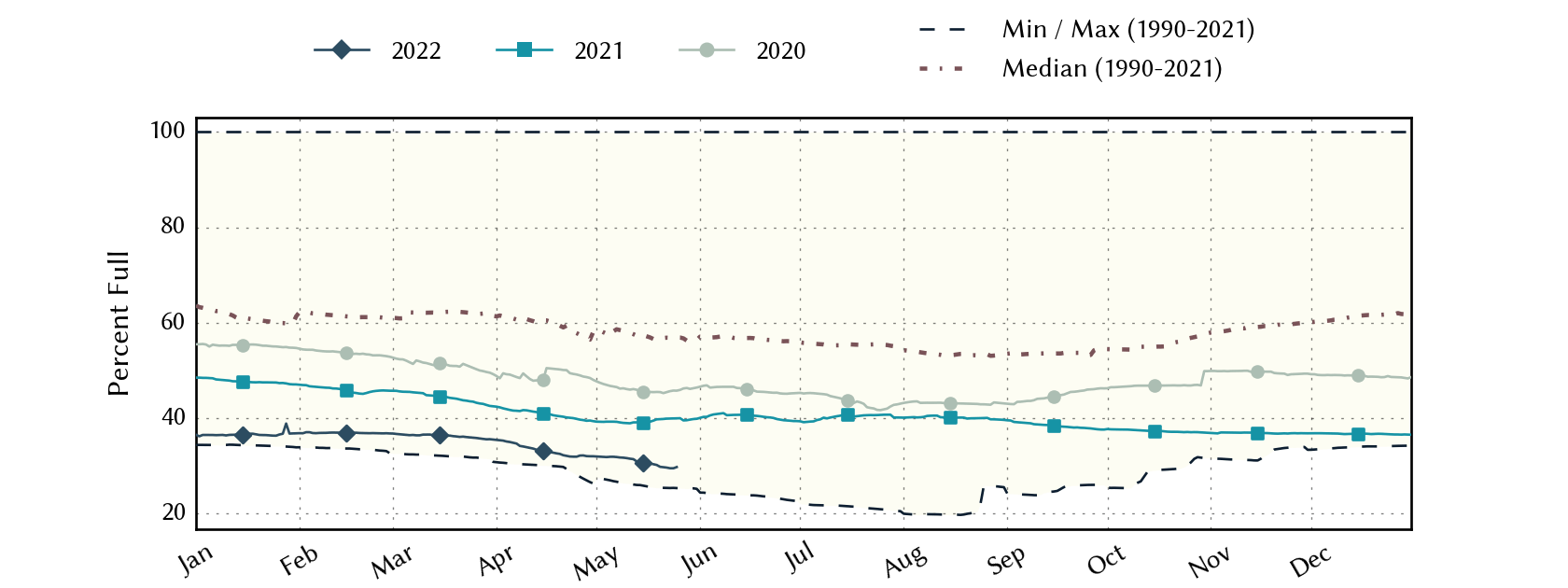

The Rio Conchos Basin in Mexico, which confluences into the Rio Grande just above Presidio and is the largest tributary to the Rio Grande, remains partially abnormally dry (but getting drier) in the Sierra Madre Occidental (Figure 4a). Combined conservation storage in Amistad and Falcon reservoirs decreased from 32.7% last month to 29.7% full today, about 30 percentage points below normal for this time of year (Figure 4d).

Figure 4a: The North American Drought Monitor for April 30, 2022 (source).

Figure 4b: Percent of normal precipitation for Colorado and New Mexico for the 90 days before May 24, 2022 (modified from source). The red line is the Rio Grande Basin. I use this map to see check precipitation trends in the headwaters of the Rio Grande in southern Colorado, the main source of water to Elephant Butte Reservoir downstream.

Figure 4c: Reservoir storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir since 2020 with the median, min, and max for measurements from 1990 through 2021 (graph from Texas Water Development Board).

Figure 4d: Reservoir storage in Amistad and Falcon reservoirs since 2020 with the median, min, and max for measurements from 1990 through 2021 (graph from Texas Water Development Board).

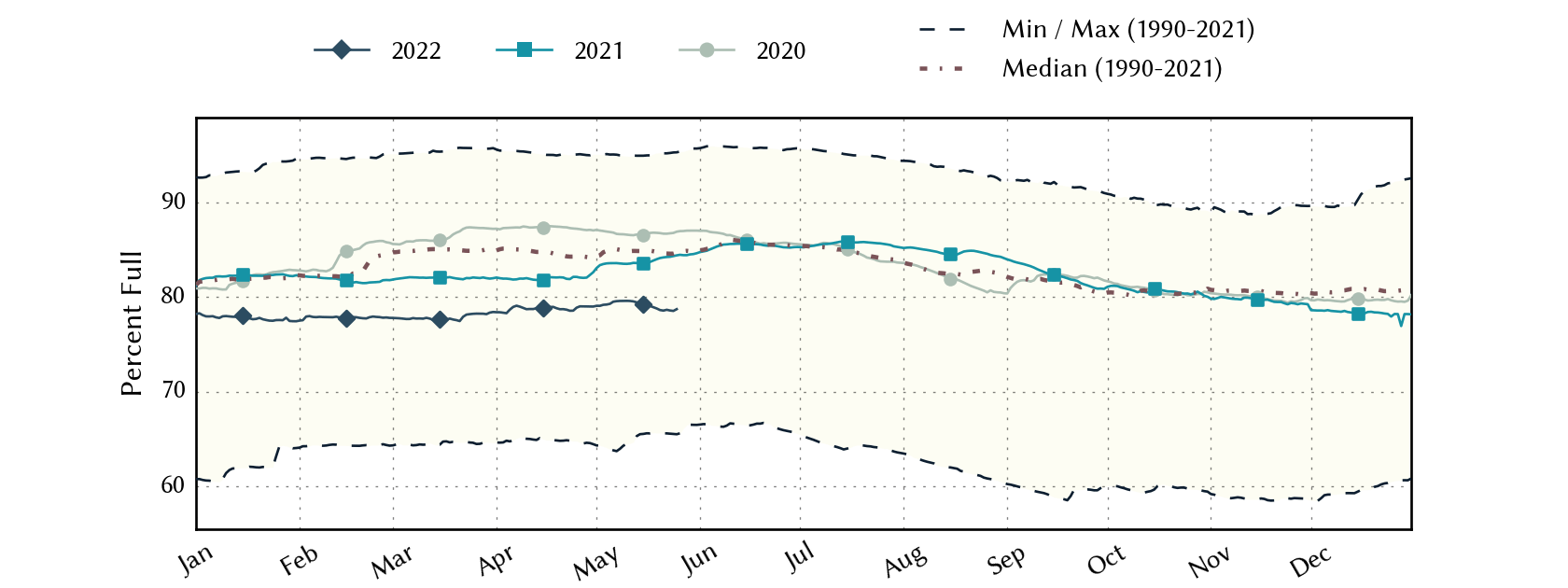

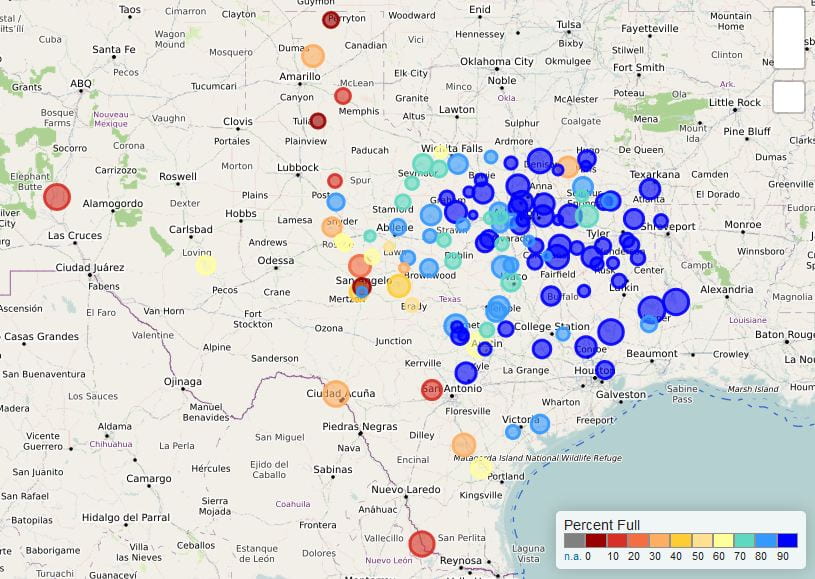

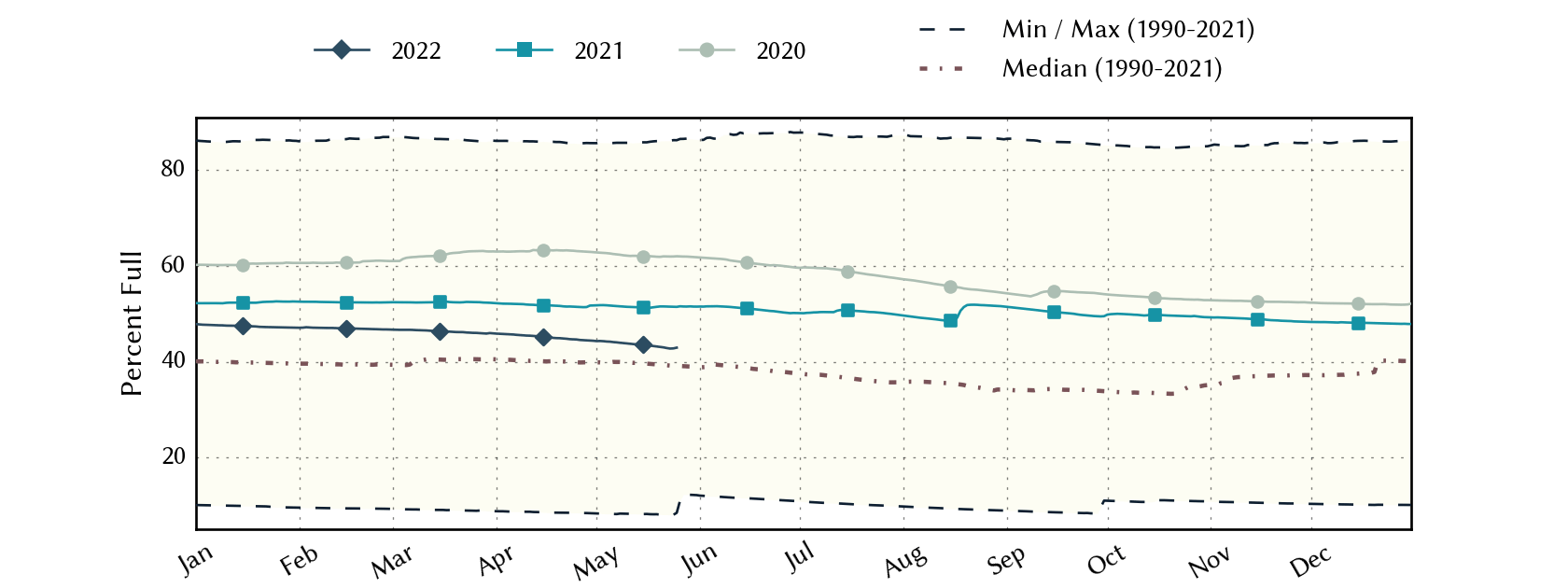

A number of basins across the state have flows over the past week below historical 25th, 10th, and 5th flow percentiles (Figure 5a). Statewide reservoir storage is at 78.7% full as of today, down 64,000 acre-feet from 78.9% a month ago, about five percentage points below normal for this time of year (Figure 5b). Unusual for this time of year, more reservoirs in the eastern part of the state have fallen below 90%, and now 80%, full, although there have been some improvements with recent rains (Figure 5c). The reservoir marked in orange northeast of Dallas (between 30 and 40% full) is accurately but perhaps unfairly orange because it, Bois D’Arc Lake, is a newborn and just started its initial inundation (Figure 5c). Reservoirs in the San Angelo area are still above normal for this time of year (Figure 5d).

Figure 5a: Parts of the state with below-25th-percentile seven-day average streamflow as of May 24, 2022 (map modified from U.S. Geological Survey).

Figure 5b: Statewide reservoir storage since 2020 compared to statistics (median, min, and max) for statewide storage from 1990 through 2021 (graph from Texas Water Development Board).

Figure 5c: Reservoir storage as of May 25, 2022 in the major reservoirs of the state (modified from Texas Water Development Board).

Figure 5d: Hydrograph of the Month—Reservoir storage for San Angelo area reservoirs (Nasworthy, O.C. Fisher, O.H. Ivie, and Twin Buttes; graph from Texas Water Development Board).

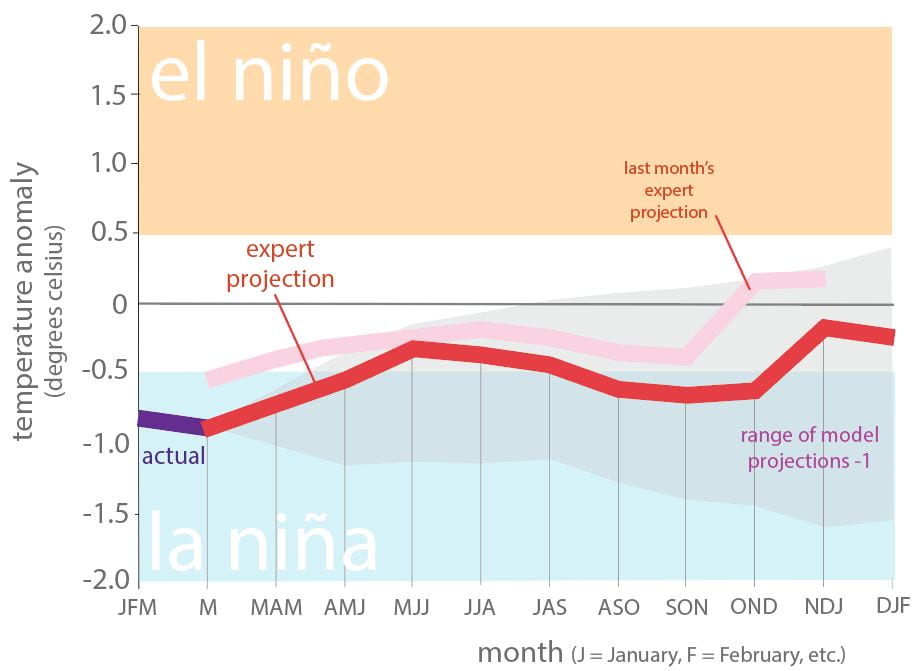

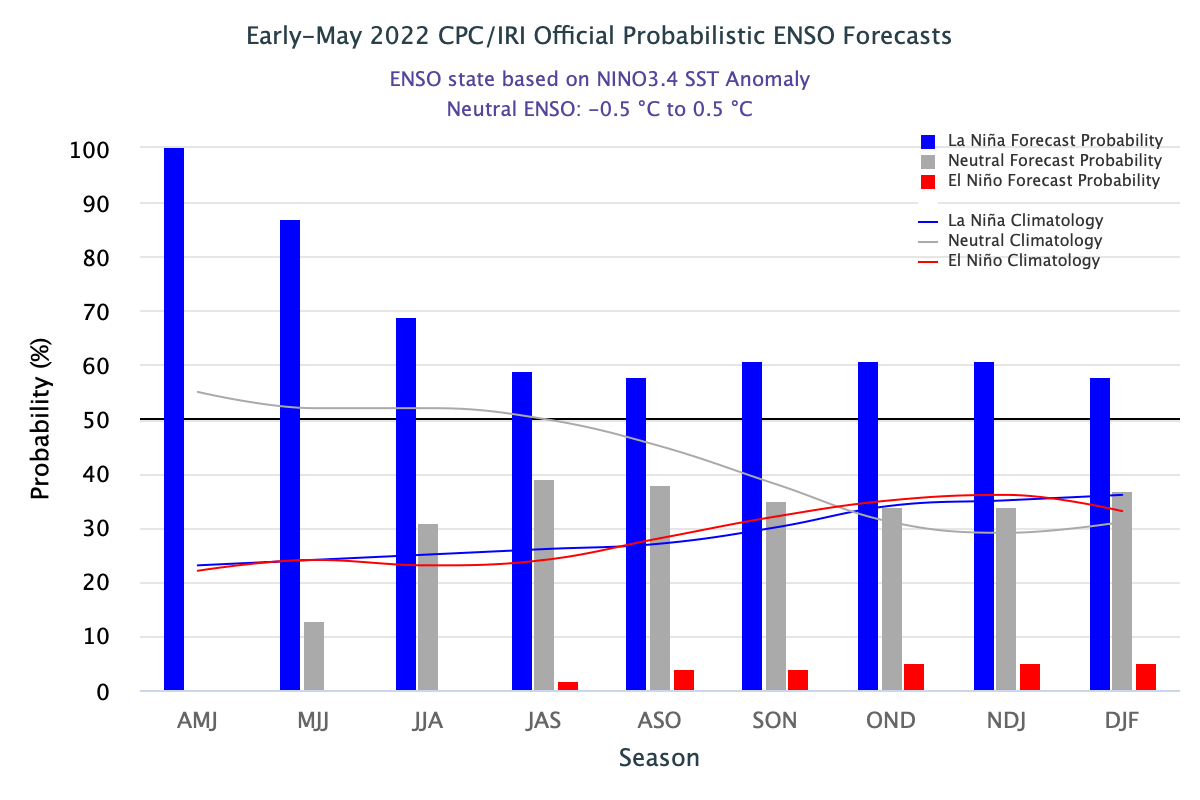

Sea-surface temperatures in the Central Pacific that in part define the status of the El Niño Southern Oscillation continue to reside in La Niña conditions and have cooled slightly, deeper into La Niña conditions (Figure 6a). This month’s projection is a bit cooler than last month’s (Figure 6a). Accordingly, we remain under a La Niña Advisory. Projections of sea-surface temperatures suggest a 58% chance of remaining in La Niña conditions through the August-October season with a 61% chance of being in La Niña through the fall and early winter (Figure 6b). The last two seasons (NDJ and DJF) show a bump up into neutral conditions; however, I believe that this is an artifact of uncertainty in projecting that far into the future.

Figure 6a. Forecasts of sea-surface temperature anomalies for the Niño 3.4 Region as of April 19, 2022 (modified from Climate Prediction Center and others). “Range of model predictions -1” is the range of the various statistical and dynamical models’ projections minus the most outlying upper and lower projections. Sometimes those predictive models get a little craycray!

Figure 6b. Probabilistic forecasts of El Niño, La Niña, and La Nada (neutral) conditions (graph from the Climate Prediction Center and International Research Institute).

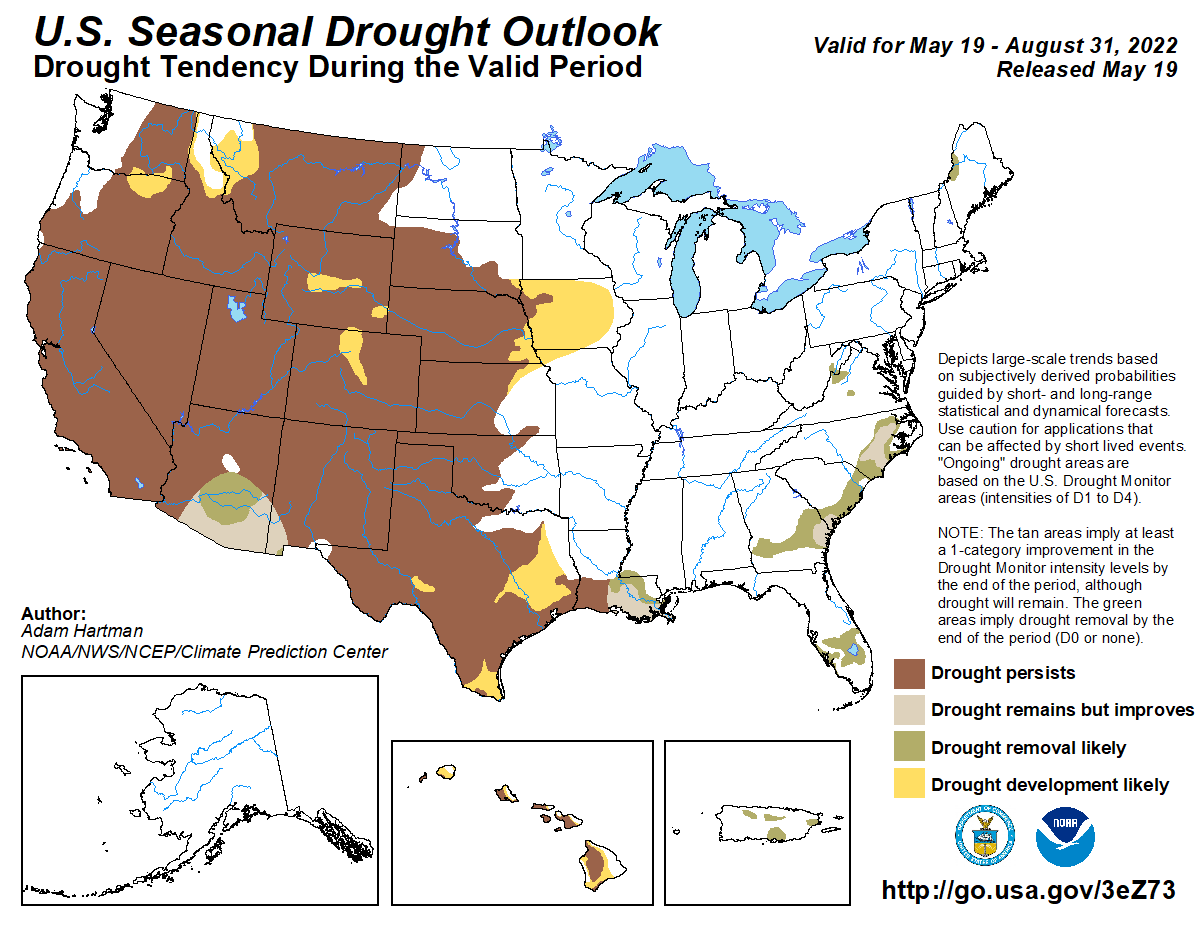

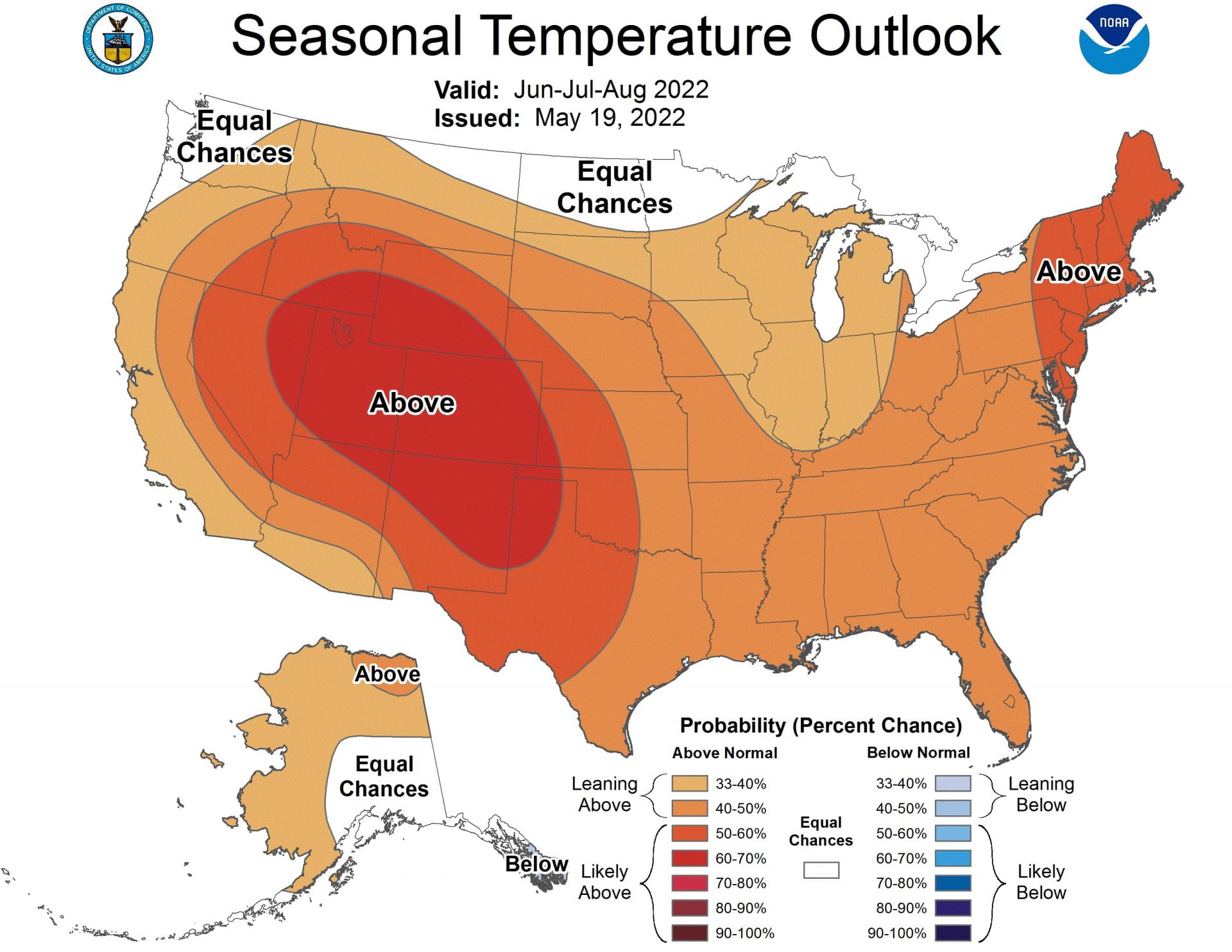

The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook through June 2022 shows the drought retreating somewhat from Louisiana and northeastern Texas (Figure 7a). Regardless, the drought outlook shows drought continuing or developing for almost the entire state (Figure 7a). The three-month temperature outlook projects warmer-than-normal conditions for the entire state (Figure 7b), while the three-month precipitation outlook favors drier-than-normal conditions for most of the western two-thirds of the state (Figure 7c).

Figure 7a: The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook for May 19, 2022, through August 31, 2022 (source).

Figure 7b: Three-month temperature outlook for June-July-August 2022 (source).

Figure 7c: Three-month precipitation outlook for June-July-August 2022 (source).