SUMMARY:

- 75% of the state is abnormally dry or worse, and 52% of the state is in drought

- Equal chances for La Niña or neutral conditions for the January-March season and a 71% chance of neutral conditions for the February-April season

- Reservoir storage is still 10% below normal, but it’s been creeping up

I wrote this article on December 15 and 16, 2022.

Well, it’s only been two weeks since the last update, but with the holidays quickly approaching, things shutting down at the university, and Dr. Votteler hitting the eggnog a little too hard, we’re getting you what we can this week.

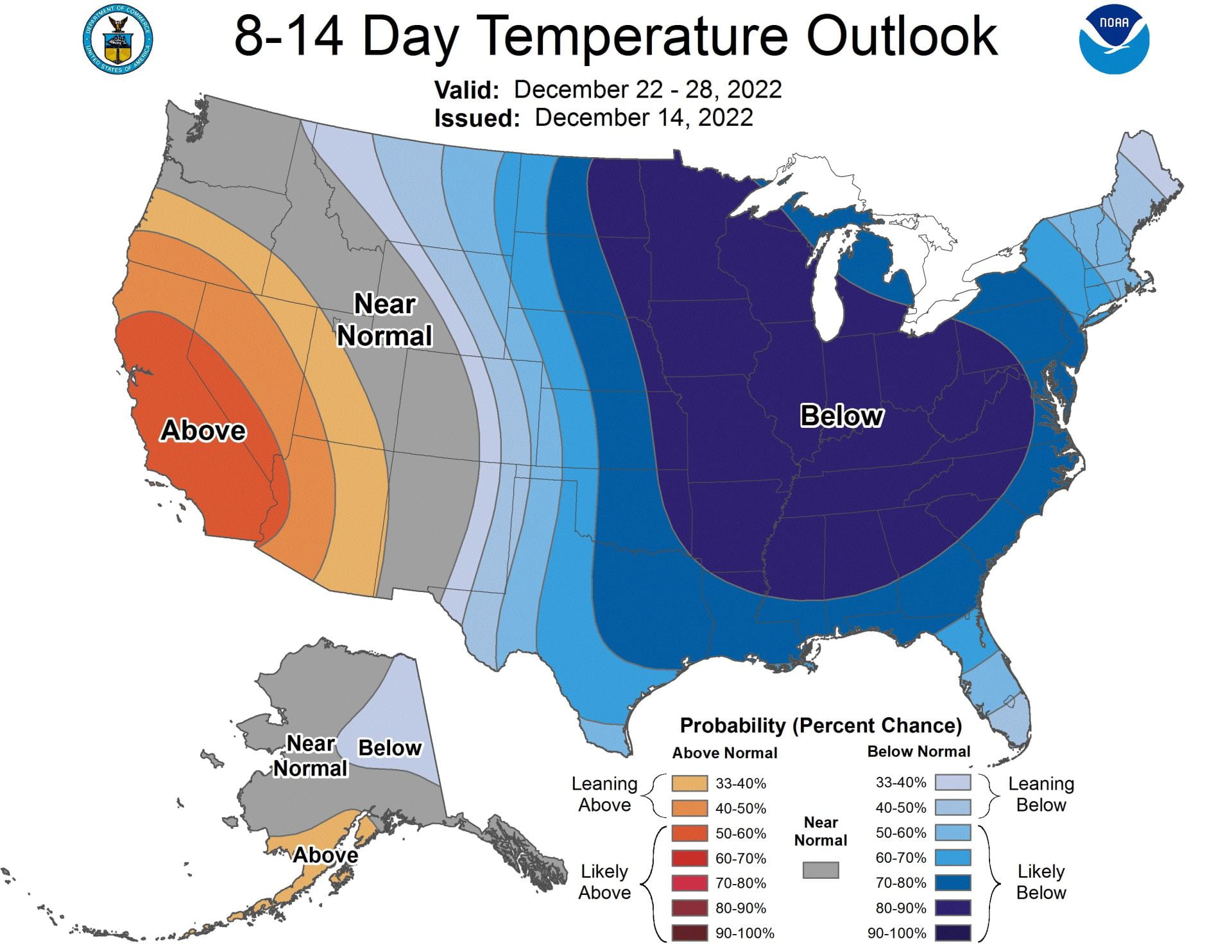

Over the next 8 to 14 days, it might not be BBQing-in-shorts or tofu-wrassling-in-swimwear weather (Figure 1a). According to one of my weather friends, the temperatures could be substantially below normal for much of Texas around the time Santa is swinging his sleigh into the Lone Star State. Keep your sweaters handy! Unfortunately, with a lower-than-normal expectation of precipitation for a large part of the state, if it does get cold, it probably won’t be a white Christmas (Figure 1b).

Figure 1a: Temperature outlook for the next 8 to 14 days (source).

Figure 1b: Precipitation outlook for the next 8 to 14 days (source).

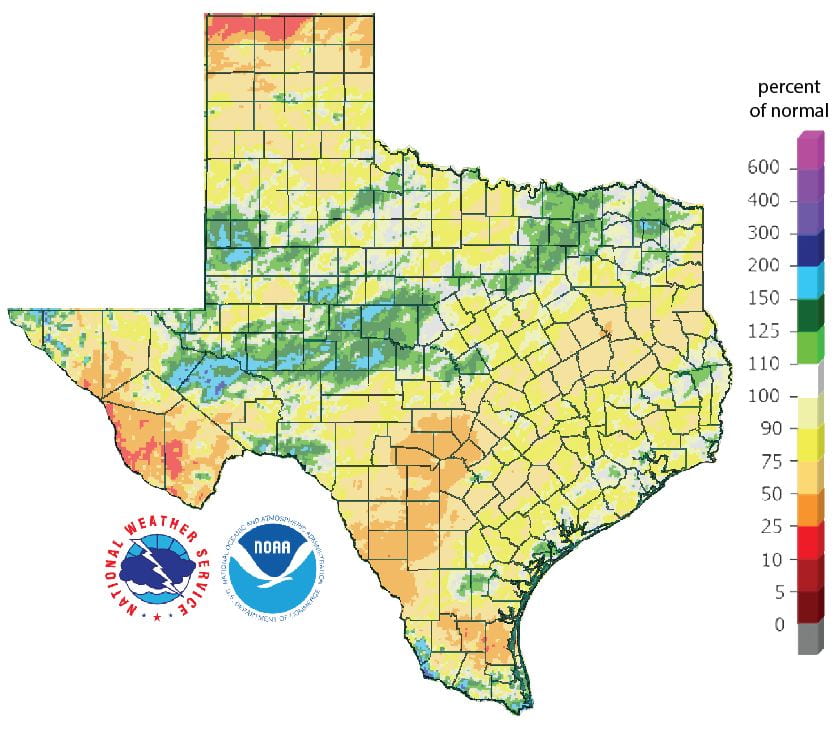

Over the past 14 days, parts of East Texas saw more than 5 inches of rain, while the Panhandle, Big Bend, South Texas, and Lower Rio Grande Valley saw less than 0.1 inches (Figure 2a). Compared to normal, rainfall over the past 14 days has been above normal in southwest-to-northeast stripes across the state and way below normal in the areas mentioned above with little rainfall (Figure 2b). Rain over the past 90 days—a big driver for drought conditions—remains below normal for almost the entire state except for parts of the Edwards Plateau and a few other spots (Figure 2c).

Figure 2a: Inches of precipitation that fell in Texas in the 14 days before December 14, 2022 (modified from source). Note that cooler colors indicate lower values and warmer indicate higher values. Light grey is no detectable precipitation.

Figure 2b: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the 15 days before December 14, 2022 (modified from source).

Figure 2c: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the 90 days before December 14, 2022 (modified from source).

The amount of the state under drought conditions (D1–D4) decreased from 63% three weeks ago to 52% today (Figure 3a), with drought decreasing in the eastern half to two-thirds of the state but with an increase near the Lower Rio Grande Valley (Figure 3b). Extreme drought, or worse, has decreased from 15% of the state three weeks ago to 7%, with exceptional drought decreasing from 2.4% to 1.4% (Figure 3a). In all, 75% of the state remains abnormally dry or worse (D0–D4; Figure 3a), down a bit from 87% four weeks ago.

Figure 3a: Drought conditions in Texas according to the U.S. Drought Monitor (as of December 13, 2022; source).

Figure 3b: Changes in the U.S. Drought Monitor for Texas between November 15, 2022, and December 13, 2022 (source).

The North American Drought Monitor, which runs a month behind, shows drought over much of the lower 48 (Figure 4a). Precipitation over much of the Rio Grande watershed in Colorado and New Mexico over the last 90 days was lower than normal except for the western part of the basin in mid-New Mexico (Figure 4b).

Conservation storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir—an important source of water for the El Paso area—increased to 10.3% full from 8.8% two weeks ago (Figure 4c), slightly above historic (since 1990) lows.

The Rio Conchos Basin in Mexico, which confluences with the Rio Grande just above Presidio and is the largest tributary to the Lower Rio Grande, remains out of drought (Figure 4a). Combined conservation storage in the Amistad and Falcon reservoirs increased slightly to 32.2% full from 31.8% two weeks ago, about 22 percentage points below normal for this time of year and below the lowest low recorded since 1990 (Figure 4d).

Figure 4a: The North American Drought Monitor for October 31, 2022 (source).

Figure 4b: Percent of normal precipitation for Colorado and New Mexico for the 90 days before December 14, 2022 (modified from source). The red line is the Rio Grande Basin. I use this map to see check precipitation trends in the headwaters of the Rio Grande in southern Colorado, the main source of water to Elephant Butte Reservoir downstream.

Figure 4c: Reservoir storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir since 2020 with the median, min, and max for measurements from 1990 through 2021 (graph from Texas Water Development Board).

Figure 4d: Reservoir storage in Amistad and Falcon reservoirs since 2020 with the median, min, and max for measurements from 1990 through 2021 (graph from Texas Water Development Board).

Basins across the state continue to have flows over the past week below historical 25th, 10th, and 5th flow percentiles (Figure 5a). Statewide reservoir storage is at 70.8% full as of December 14, up about 350,000 acre-feet from 69.7% two weeks ago and now about ten percentage points below normal for this time of year (Figure 5b).

Many reservoirs in the eastern part of the state remain less than 90% full, with many reservoirs less than 80% full and some even less than 70% full (Figure 5c). The reservoir marked in orange northeast of Dallas (between 50 and 60% full) is accurately but perhaps unfairly orange since it, Bois D’Arc Lake, is a newborn and just started its initial inundation earlier this year (Figure 5c). Recent rains benefited the Waco reservoir, but it remains below normal by 37 percentage points for this time of year, although now it is no longer below historic (since 1990) lows (Figure 5d).

Figure 5a: Parts of the state with below-25th-percentile seven-day average streamflow as of December 14, 2022 (map modified from U.S. Geological Survey).

Figure 5b: Statewide reservoir storage since 2020 compared to statistics (median, min, and max) for statewide storage from 1990 through 2021 (graph from Texas Water Development Board).

Figure 5c: Reservoir storage as of November 29, 2022, in the major reservoirs of the state (modified from Texas Water Development Board).

Figure 5d: Hydrograph Of The Month—Reservoir storage for the Waco area reservoir (Waco; graph from Texas Water Development Board).

Sea-surface temperatures in the Central Pacific that, in part, define the status of the El Niño Southern Oscillation continue to reside in La Niña conditions but warmed a bit over the previous season (August-October) (Figure 6a). This month’s projection is warmer than last month’s but suggests that La Niña conditions will remain through the winter (Figure 6a). Accordingly, we remain under a La Niña Advisory. Sea-surface temperature projections show a continuation of La Niña into the winter, equal chances of La Niña and La Nada (neutral conditions) for January-March, and a 71% chance of La Nada for February-April (Figure 6b).

Figure 6a. Forecasts of sea-surface temperature anomalies for the Niño 3.4 Region as of November 18, 2022 (modified from Climate Prediction Center and others). “Range of model predictions -1” is the range of the various statistical and dynamical models’ projections minus the most outlying upper and lower projections. Sometimes those predictive models get a little craycray.

Figure 6b. Probabilistic forecasts of El Niño, La Niña, and La Nada (neutral) conditions (graph from Climate Prediction Center and others).

The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook through March 2023 shows improvement from last month, with drought leaving East Texas; however, it also shows drought developing across the lower Gulf Coast area in Texas and in the northern bits of the Edwards Plateau (Figure 7a). In a bit of bad news, the weather warlocks now project drought development to the west of us in Arizona and New Mexico—drought continues to our north (Figure 7a). In my experience, these super-regional droughts have more persistence than regional and subregional droughts. Like a broken record, the three-month temperature outlook projects warmer-than-normal conditions for most of the state (Figure 7b), while the three-month precipitation outlook favors drier-than-normal conditions for the entire state (Figure 7c).

Figure 7a: The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook for December 15, 2022, through March 31, 2023 (source).

Figure 7b: Three-month temperature outlook for January-February-March 2023 (source).

Figure 7c: Three-month precipitation outlook for January-February-March 2023 (source).