In this issue’s Q&A, Texas+Water Editor-in-Chief, Dr. Todd Votteler, interviews State Representative Lyle Larson and Senator Charles Perry to get their take on the 86th Texas Legislative Session.

Chairman Lyle Larson,

Chairman Lyle Larson,

House Natural Resources Committee

In 2010, Representative Lyle Larson was elected State Representative for District 122. Larson was reelected to a fourth term in 2016.

Currently, Larson serves as the Chair of the House Natural Resources Committee, as a member of the House Committee on Redistricting, and the International Relations and Economic Development Committee.

What do you think was the most significant accomplishment regarding water by the 86th Texas Legislature during the session, and why?

The Legislature passed a series of monumental bills that will help better prepare communities for floods. The State was able to accomplish in one session what took many sessions for water supply. Going forward there will be a robust process for planning for and implementing flood projects.

We were also grateful for the support from members in both chambers on a number of innovative water supply bills that were multiple sessions in the making.

What do you think was the most significant failure regarding water by the 86th Texas Legislature during the session, and why?

Over the last interim, the Natural Resources Committee held public hearings on the Saba Saba River and Devil’s River to further the discussion on conjunctive use. The interaction between groundwater and surface water has caused surface water flows to dry up in certain areas because of groundwater wells drilled near their banks. The State of Texas is suing New Mexico on this very premise in federal court, while not refereeing it within its own borders.

Ultimately, this is going to be exacerbated when the State enters the next serious drought, and will have an adverse impact on creeks and tributaries that flow into all our large river basins. Policy solutions are needed to address the issue of given the two different types of water ownership for groundwater and surface water and varying regulatory regimes.

During your time in the Texas Legislature what is the most significant thing you have done regarding water?

As we’ve discussed many times over the course of the last five sessions, aquifer storage and recovery (ASR) and desalination are the new horizon for securing our State’s water future. Exposing folks across the State to these technologies will help them better address water insecurity issues, particularly in light of the drought conditions the entire State will continue to experience.

Legislation passed this session and in past sessions hopefully will have a profound impact on the development of these types of projects. Both with brackish groundwater desalination and ASR, we have worked on developing the State’s science to support these types of projects and then tailoring a regulatory environment that encourages their development.

Upon the Texas Water Development Board‘s completion of the ASR study prescribed by House Bill 721, the State will soon know the aquifers most conducive to storing water underground, allowing the State to identify synergies with water users overlying these areas that could take advantage of this innovative water management strategy. It will also work hand-in-hand with House Bill 720, legislation that will incentivize a water user to develop an ASR project over another type of surface water project by providing for an expedited permit for a user who commits to capture and store unappropriated surface water underground. Water from all river basins in Texas should be collected and stored through ASR when we have excess water in years of high rainfall. House Bill 655 passed in the 85th Legislative Session was also critical to clarifying that permitting for an ASR project is squarely within the jurisdiction of the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, and streamlined the permitting process.

House Bill 30 from the 85th Legislative Session and House Bill 722 passed this session promotes the development of brackish groundwater, one of the must robust but underdeveloped water supplies in Texas. House Bill 30 provided for the science, requiring the Texas Water Development Board to study the State’s brackish aquifers and identify Brackish Groundwater Production Zones where brackish groundwater can be produced without impacts to fresh groundwater. House Bill 722 sets forth a regulatory environment in zones that are within the boundaries of one of the State’s 100 groundwater conservation districts that will encourage development of projects. Together these bills have put tens of thousands of acre-feet online for development based on current zone designations.

Finally, the State can begin to take a more active role in developing ASR, desalination and inter-regional water supply projects through the State Participation Program based on the passage of House Bill 1052 this session.

With the passage of these bills, Texas is moving towards smarter water management as other States have already embarked upon to bolster their water supplies and manage droughts.

Is there something you think the Federal government should, or should not, be doing regarding Texas water?

For decades, the United States has failed to hold Mexico accountable for its violations of the spirit of the 1944 Treaty for the Utilization of Waters of the Colorado and Tijuana Rivers and of the Rio Grande, which continues to negatively impact the economy along our southern border.

Under the 1944 Treaty, Mexico is required to deliver 350,000 acre-feet of Rio Grande water on a consistent basis to Texas, though it seldom complies, frequently abusing a provision that exempts compliance if they claim “extraordinary drought or serious accident”, and leaving farmers and cities in the Rio Grande Valley at the mercy of their release schedule. Meanwhile, the United States has a spotless record honoring its obligation under the Treaty to provide 1.5 million acre-feet from the Colorado River, nearly five times the amount of water, to Mexico.

This has had an adverse impact, not only on Texas, but also on the Colorado River lower basin states of California, Nevada and Arizona, which have moved heaven and earth to meet its obligations under the Treaty in spite of unprecedented drought, as reflected in the historically low elevations in Lake Mead. The unfair and one-sided adherence to the Treaty has allowed agricultural economies to flourish in Mexico, and meanwhile, has caused economic hardship for irrigators and cities in the Rio Grande Valley who depend on this water supply. According to a study by the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service, the loss of irrigated crop production in the Lower Rio Grande Valley region due to water shortages is estimated to cause a $343.5 million loss in economic output over a five-year period.

While Mexico is currently caught up on deliveries due to heavy rainfalls, an update to the Treaty is needed as a long-term solution to ensure the Rio Grande Valley can rely on these supplies when they are sorely needed in a drought.

The federal government should adjust the allocations in the treaty to 500,000 acre-feet from Mexico and 1 million acre-feet going to Mexico from the United States. These adjustments would help the Rio Grande Valley’s booming population and allow more water to be stored in Lake Mead to help the folks in Arizona, Nevada and California. These releases on the Colorado River into Mexico should be synced with the Rio Grande River coming out of Mexico to provide an incentive for both sides to comply.

This is an important issue for Texas and should not go unaddressed as we work through challenges with our southern neighbor on immigration, trade, and other issues.

What do you consider the biggest future challenge facing Texas with regard to water?

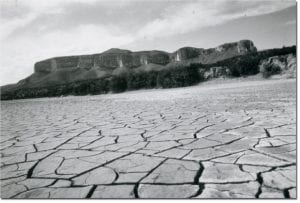

In 2016, we tasked the Texas Water Development Board to model what our State’s groundwater and surface water resources would look like if the drought of 2011 had endured for another five years, as climatologists predict will happen in the next century based on tree ring analysis and data collected over the last five centuries.

According to the Board’s model, if 2011 conditions persisted for five years, 70 of the State’s 117 reservoirs would have been completely dry. Aggregate surface water storage would have dropped from 19.4 million acre-feet at the end of 2011 to 4.9 million acre-feet at the end of 2015. The projected effect on groundwater resources would have been equally devastating.

The 2011 drought proved we weren’t prepared to meet the needs of Texans. This virtual model projects what Texas will experience sometime in the next century when an even worse drought takes hold, and should drive policymakers to take bold steps to prepare for the next drought, as our predecessors did in response to the drought of the 1950s.

Implementation of a comprehensive and thoughtful water supply plan and creating a regulatory environment that ensures water can move where it’s needed will be critical to meeting Texas’ growing needs.

Okay, it is time for the way-too-early look at water in the 87th Texas Legislature. What Texas water issues do you think might interest the House?

There is still work to be done to secure Texas’ water future. A few of the ideas that may be of interest in the Texas House include:

Texas needs greater efficiency and flexibility to transfer water from one water user to another through market mechanisms, and to convey water from areas of relative abundance to areas of relative shortage. The State should look at how it could benefit from the development of a Water Grid, that includes an integrated network of pipelines, pumping stations, reservoirs, and other works for the conveyance of water, as well as other policy changes that could aid in this effort.

The oil and gas industry produces and handles millions of gallons of water each day, often in water-scarce regions of Texas, but most of this water is disposed of in deep injection wells. The State should evaluate opportunities to safely encourage the treatment and reuse of this resource to meet the water needs of the oil and gas industry, as well as irrigation, industrial use, to supplement environmental flows, and eventually even municipal use.

The State should review groundwater policies, including: the process for establishing Desired Future Conditions and ensuring that those planning decisions are made on a regional basis, and ensuring that groundwater conservation districts are not impeding the development and movement of groundwater across district boundaries.

There will also be an interest in looking at other ways to secure the State’s water supply to prepare for the next drought on the horizon, to include the development of large scale projects that could benefit multiple regions, and continuing to work with neighboring states to bring additional water supplies to bear for Texas like the State did with Lake Texoma and Toledo Bend. Future projects could be large scale ASRs, brackish desalination plants, or other strategies to increase water inventories for growing populations.

Chairman Charles Perry,

Senate Water and Rural Affairs Committee

Charles Perry, a practicing CPA from Lubbock, was elected to the Texas Senate in 2014 after first serving two terms in the Texas House of Representatives.

Charles Perry, a practicing CPA from Lubbock, was elected to the Texas Senate in 2014 after first serving two terms in the Texas House of Representatives.

Perry currently chairs the Senate Committee on Water & Rural Affairs and sits on the Senate Committees for Criminal Justice, Health and Human Services, and Transportation. Additionally, he co-chairs the State Water Implementation Fund for Texas (SWIFT) Advisory Committee, and was appointed by Gov. Abbott to the Southwestern States Water Commission.

What do you think was the most significant accomplishment regarding water by the 86th Texas Legislature during the session, and why?

Hurricane Harvey recovery was a big topic of conversation leading up to and during the legislative Session. Additionally, West Texas faced several major floods in fall 2018. These major storm events are statewide issues and needed to be addressed with recovery options but also future planning. Passing Senate Bills 6, 7, and 8 began the process to flood proof our State.

Specifically, Senate Bill 8 creates the first ever State Flood Plan for Texas housed at the Texas Water Development Board (TWDB). Following the State Water Plan model, TWDB will create regions on a watershed basis for future flood strategies solutions that don’t flood neighbors to fix each regional problems.

Throughout the legislative session, the Senate Water & Rural Affairs Committee continued to discuss water supply. That conversation will continue into the interim.

What do you think was the most significant failure regarding water by the 86th Texas Legislature during the session, and why?

If you look at what we faced going into this legislative session, I believe we accomplished what we set out to do. We passed major legislation that addressed flooding.

During the previous interim, we started a major water supply conversation, but it was put on hold when Hurricane Harvey struck followed by the flooding in fall 2018.

The committee will again take up this important issue to ensure Texas has the water we need for the future.

During your time in the Texas Legislature what is the most significant thing you have done regarding water?

We’ve accomplished a lot in the water world, so not one single thing could be the most significant. I was proud to author the first State Flood Plan with funding included to begin mapping the entire State.

Earthen dam rehabilitation is an issue I have been pursuing over the course of several sessions. As of today, there are 499 high hazard dams in Texas needing rehabilitation and upgrade to meet high hazard criteria, an increase of 11 dams since January. SB 500 includes $150 million to begin the process of addressing the needs of the dams and supplying State funding to match a potential $1 billion in federal funding. The dams are scattered throughout the State making this a statewide issue.

We have continued to make water permitting efficient and transparent. The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality has reduced the time it takes to fulfill pending permits by streamlining the process. We have continued to assist the agency with fixes to their permitting where possible.

We’ve taken new steps to expedite certain processes that encourage the use of saltwater desalination. In the 85th Legislation, I authored SB 1430 which expedited an amendment to a water right permit when a user begins using desalinated water. We’ve also clarified the process for brackish groundwater permitting.

As conversations have continued with water policy, I have always championed private property rights. Texans own the water beneath their land, and therefore, we must continue to protect this right in the future.

Is there something you think the Federal government should, or should not, be doing regarding Texas water?

We are facing a national issue regarding water both flood and drought. If you watch the national news right now, you see stories about the Mississippi River and Arkansas River basins facing catastrophic flooding while the Southeast and Northwest corners of the United States plus Hawaii are gripped with severe drought. We need a national conversation about water.

There is a role for water infrastructure that develops water supply and prevents flooding. Specifically, the country is surrounded on three sides by two oceans and a gulf. The long-term viability of any nation is limited by the amount of water that is available to develop civilization. As our discussions continue into the interim, the Federal role will be one of the points covered and how to secure water for every corner of the country.

What do you consider the biggest future challenge facing Texas with regard to water?

The biggest future challenge facing Texas regarding water, and the overall future of the State, is the lack of urgency and awareness as to the status of water supply in Texas.

The 2011 drought forced our State to look at our water strategies, our planning, and begin thinking in terms of new innovation to extend our current water sources and develop new ones. Even though Texas is currently over 90 percent drought free, our eyes must always be towards the future and how we can adequately plan for the next time with little to no water. Just one year ago, 57 percent of the State was under some degree of drought.

Our State Water Planning process is great avenue for knowing what our future needs are and how we can cover the growth in our State. We must pursue those strategies listed in the plan rather than letting them sit on a shelf. Texas still does not have a complete saltwater desalination plant producing water.

Okay, it is time for the way-too-early look at water in the 87th Texas Legislature. What Texas water issues do you think might interest the Senate?

In the interim, I intend to dig into water supply and how Texas can best cover our future growth and water shortages. Even with the State out of drought, we will still not have enough to manage the population and industry growth in our State.

With bold ideas, I believe Texas can continue to lead the country in water resource management. One such idea, with discussion beginning during the 86th Legislative Session, is utilizing the produced water from fossil fuel production as a water source. Industry believes they can begin production on this new water source within the next several years with the potential to supply the State in perpetuity. We must explore these bold ideas in the interim through careful study of private property rights, costs, feasibility, and the effect on our economic growth.