SUMMARY:

-

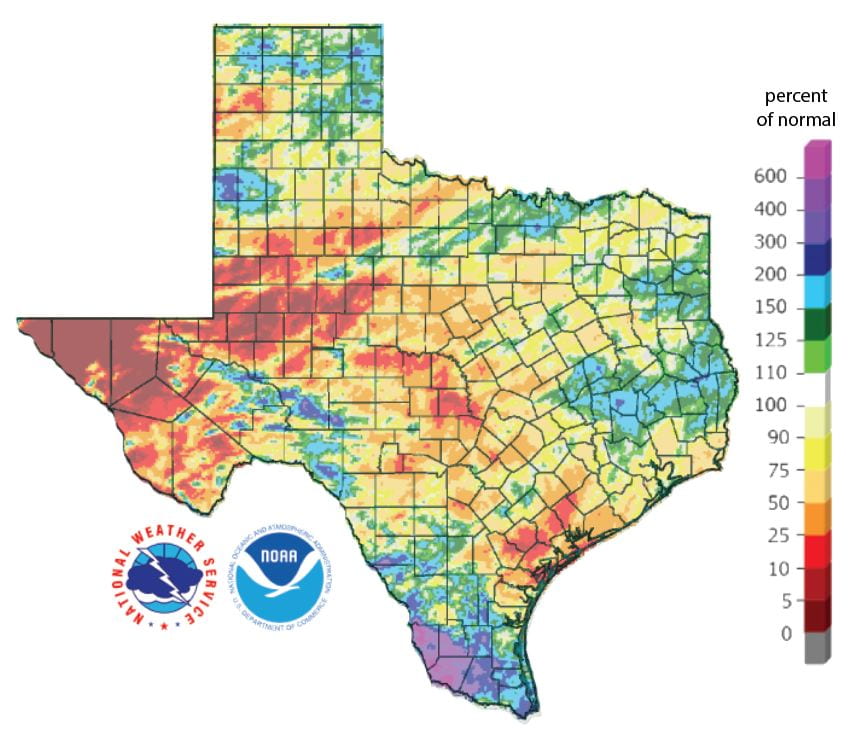

88% of the state is in drought with 14% of the state under exceptional drought conditions

-

La Niña is expected to continue through summer and possibly into the fall

-

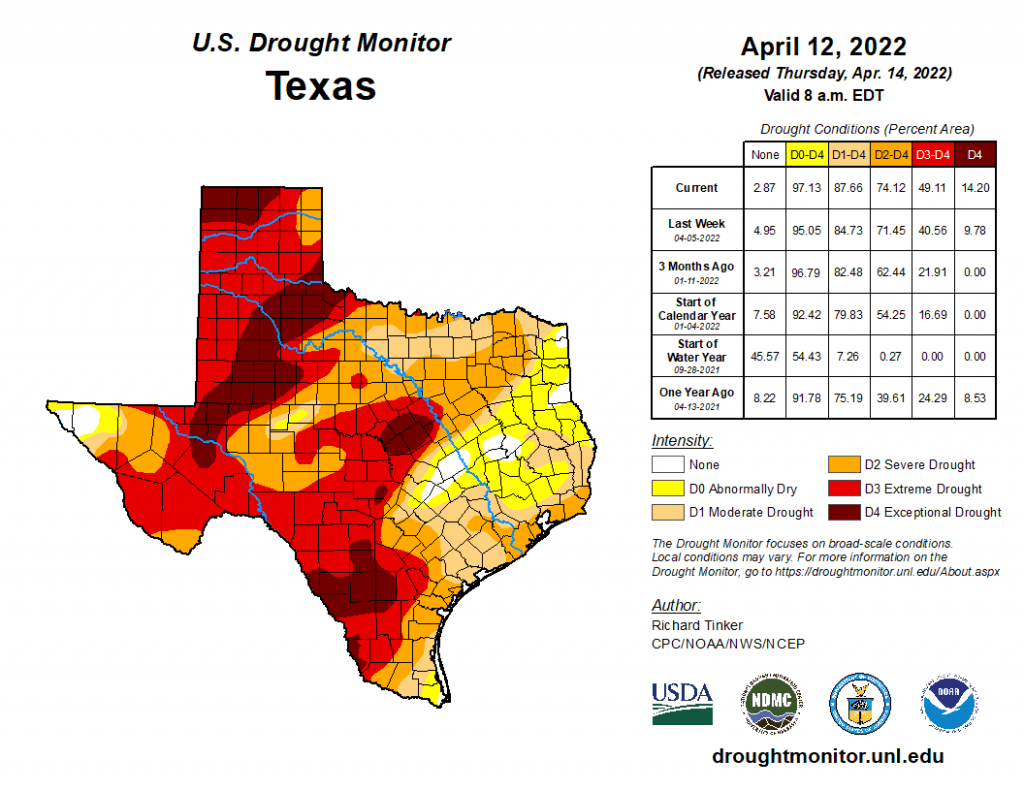

Colorado State University predicts 19 named tropical storms (1991-2020 average = 14.4) with 9 hurricanes (average = 7.2) and 4 major hurricanes (average = 3.2)

I wrote this article on April 18, 2022.

When we landed in Keflavik, Iceland, we were greeted with a full-on blizzard with horizontal snow snaking across the tarmac. After boarding the bus, we began the hour or so trek into Reykjavik. Icelanders like to keep things warm, so the plane, the airport, and the bus were, for my taste, uncomfortably toasty. The weather improved as we approached the capital city, the sun beaming through the clouds, the winds settling into a casual stroll. The bus unexpectedly dropped us off about two blocks from the hotel. Given the sun and the calm breeze (and a short two blocks), I didn’t bother to suit up in my winter gear. A light jacket and moccasins would get me there.

Over a mere distance of 30 feet from the bus stop to the street corner, it all went to hell. The sun suddenly disappeared, replaced by gale-force winds of 50 to 60 miles per hour shooting snow and sleet directly into our faces. In a literal blink of a sleet-pelted eye, we were in an epic blizzard.

The crosswinds at the first intersection took one piece of luggage I was pulling airborne as we navigated through traffic. The sleet and snow soon covered my glasses, and I could barely see The Bride — more appropriately dressed — as she disappeared into the white haze several feet in front of me.

I made it to the next intersection but couldn’t see a dang thing through the careening sleetsnow. The cold was starting to sting, especially my bare hands, while the sleet bit my face like an angry barrel of cobras. I couldn’t take waiting anymore and just heaved myself across the second intersection, cars coming or not. After another 50 feet of struggling and now in serious pain, I muttered to myself, “Where the holy boo rag is this place?”

I couldn’t take another step without gloves, so I stopped to locate more appropriate attire. As I stooped down to open the luggage, I saw that my jacket was only zipped up halfway and that the upper, unzipped part was now packed with snow. As I struggled to keep our underwear from blowing up Laugavegur while searching for gloves, I heard The Bride yelling, “BUBBA! BUUUBBAAAA!” I looked but couldn’t see her. Was I dying and now hearing phantom voices in the howling winds? Was this how it would end?

After five minutes of panicked searching, I only found one glove. “I’m not gonna make it,” I whispered to myself as I knocked the snow off my chest and pulled on my one glove. I didn’t know how much more I had in me, but I was going to give it my all. And just like a scene in a Jack London book, as I stumbled forward in disoriented fury, it turned out I was only 10 feet away from the front door of the hotel. As I collapsed into the hotel’s foyer, the receptionist pleasantly chirped, “Welcome to Iceland!”

“What the hell were you doing out there?” my understanding wife asked. “You were only 10 feet away from the front door! I was watching you through the window!” She casually sipped her latte.

“Dying,” I accurately replied. “Why didn’t you come out and help me?”

“I wasn’t going back out there!”

And then the winds suddenly calmed, and sun came out again. It turns out that in Iceland, at least in March, you only have to wait 10 minutes for the weather to change.

Spring in Texas can also be exciting, but it’s excitement of a different sort. Several strong storm systems passed through the state providing some rain (and snow!) to some parts of the state but missing others. Unfortunately, these systems also brought golf-ball sized hail and tornados. One evening in Iceland we surreally watched a tornado churn through I-35 and 45 — near where one of our cats (Mr. P.S. Church) was boarded — live via Twitter.

Although the rains from these systems have helped, Texas is still in a bad place drought-wise. It also appears that La Niña conditions are likely to continue through the summer and into the fall — not good news if this happens. The good news is that most reservoirs remain mostly full, and we remain well above historic lows.

La Niña conditions, or more accurately the lack of El Niño conditions, generally means a more-active-than-normal hurricane season, and that’s exactly what Colorado State University has predicted for 2022 in its April forecast. They predict 19 named storms (1991–2020 average = 14.4) with nine hurricanes (average = 7.2) and four major hurricanes (average = 3.2). They also predict a 71% chance of a major hurricane hitting the U.S. coastline (average chance over the last century is 52%) and a 46% chance of a major hitting the Gulf Coast from the Florida Panhandle to Brownsville (average = 30%). For Texas, they put an 80% chance of a named storm coming within 50 miles of our coast (normal = 60%), a 54% chance of a hurricane (normal = 36%), and a 25% chance of a major hurricane (normal = 16%). Colorado State will provide forecast updates in June, July, and August as well as a post-audit on how well they did at the end of November.

Figure 1: Colorado State University’s April forecast for 2022 hurricane activity (source).

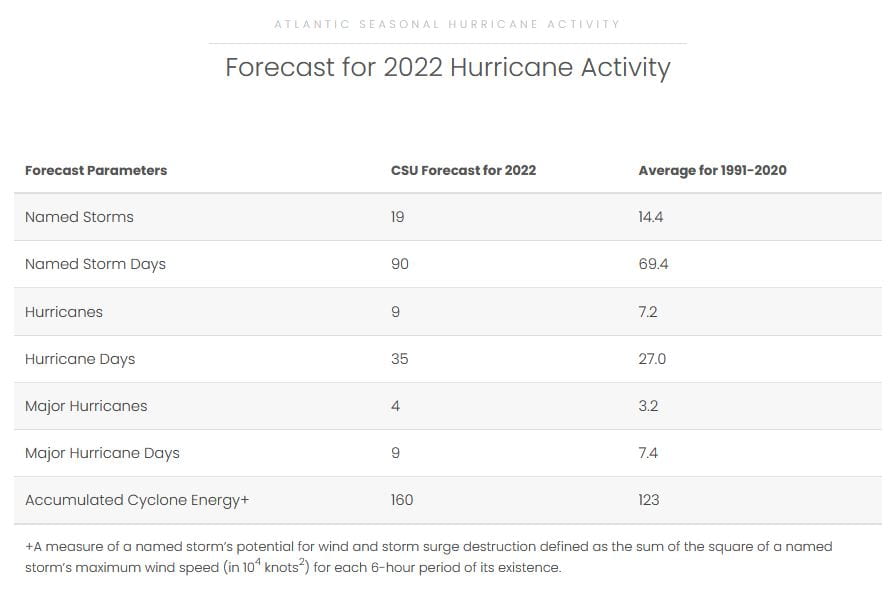

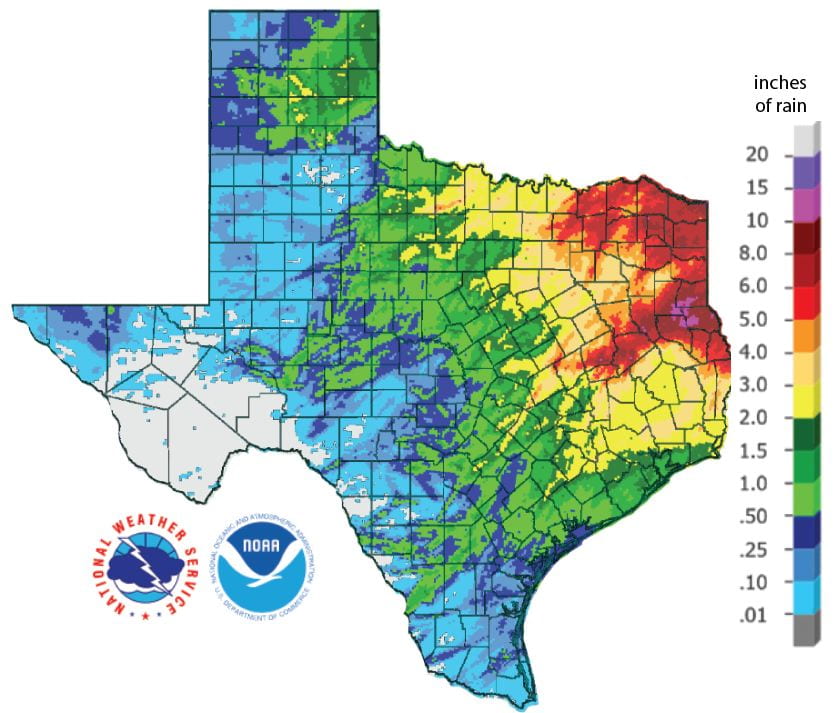

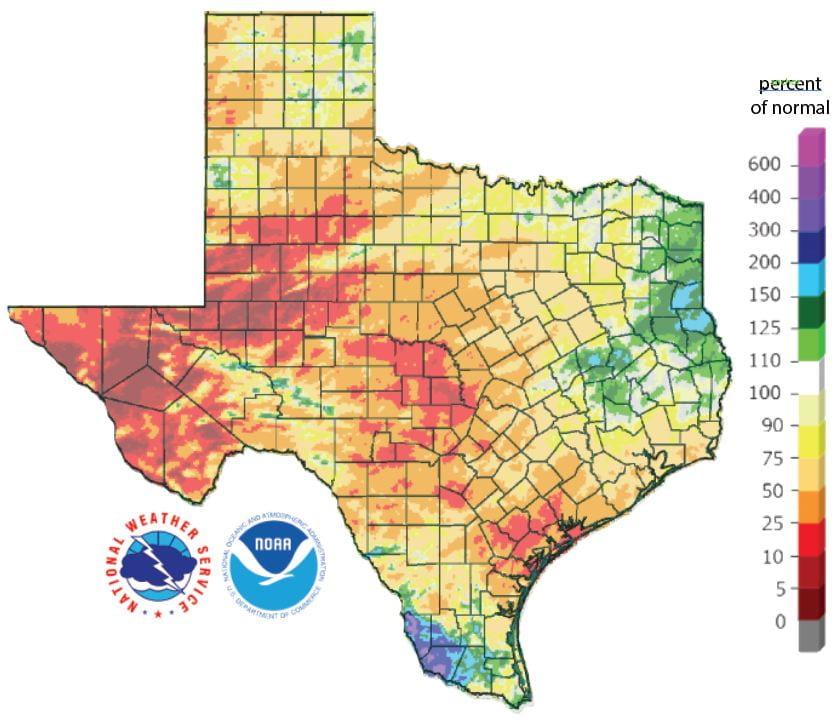

Over the past 30 days, we’ve seen the usual wetter-in-the-east-and-drier-in-the-west pattern with upwards of 6 to more than 10 inches of precipitation, with less than half an inch for much of the western and southwestern parts of the state (and no rainfall for much of the Big Bend area; Figure 2a). Compared to normal conditions, the past 30 days look better than last month but much of the state received less than 25% of normal precipitation (Figure 2b). Rain over the past 90 days — a big driver for drought conditions — remains below normal for almost the entire state, with much of the state having received less than 50% of normal precipitation (Figure 2c).

Figure 2a: Inches of precipitation that fell in Texas in the 30 days before April 18, 2022 (modified from source). Note that cooler colors indicate lower values and warmer indicate higher values. Light grey is no detectable precipitation.

Figure 2b: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the 30 days before April 18, 2022 (modified from source).

Figure 2c: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the 90 days before April 18, 2022 (modified from source).

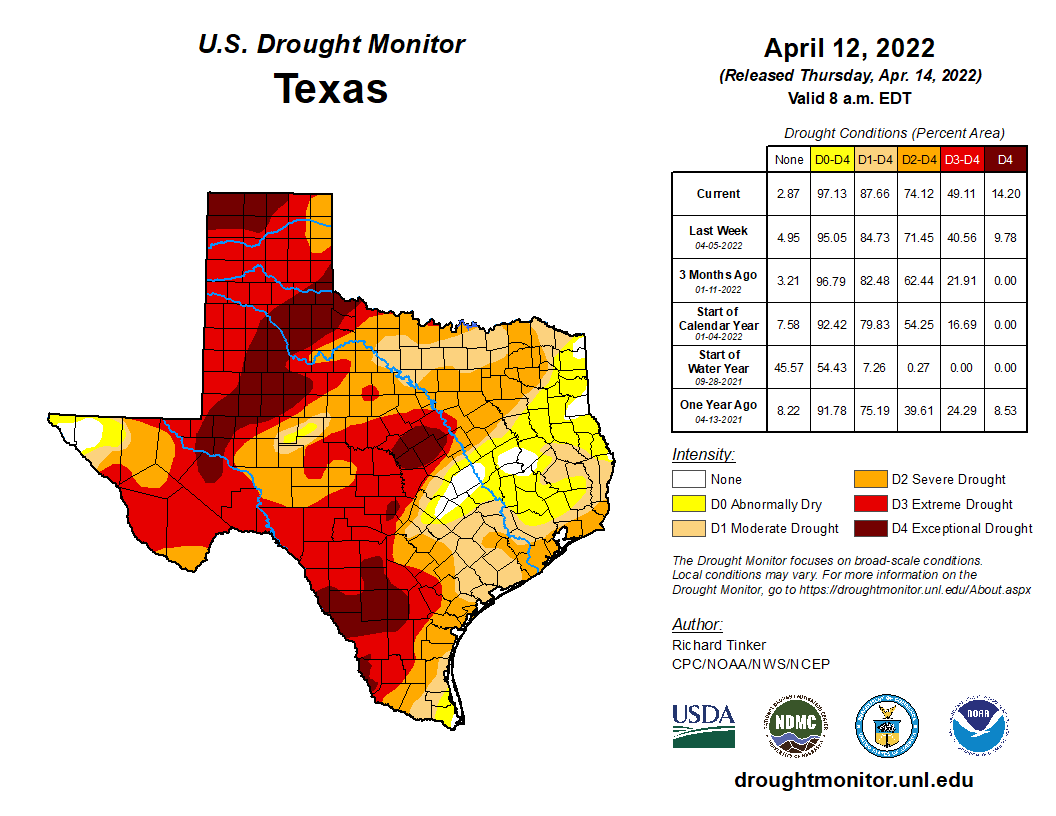

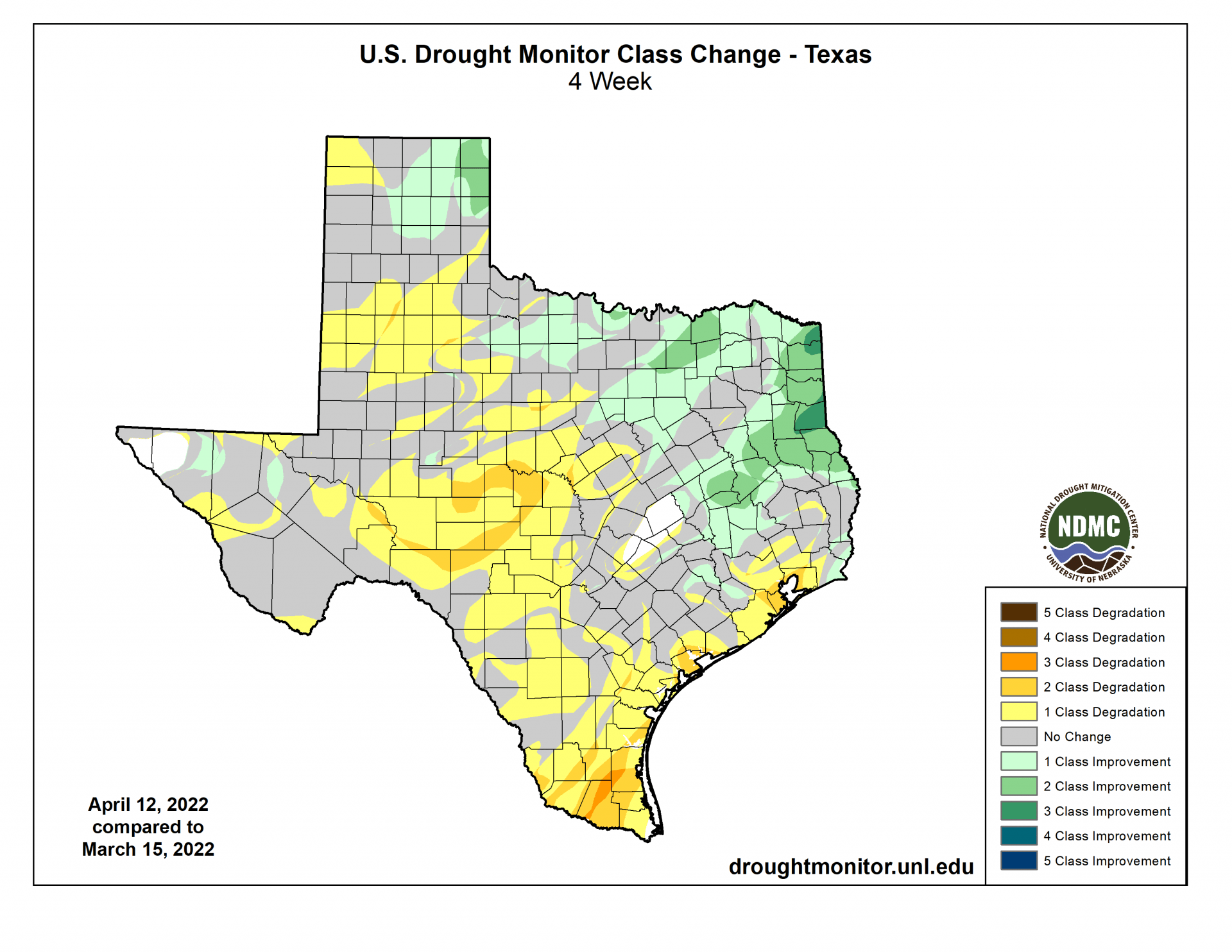

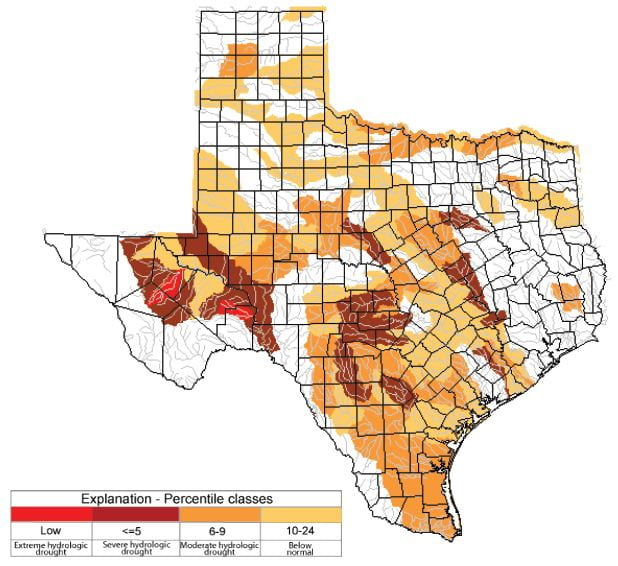

The amount of the state under drought conditions (D1–D4) decreased slightly from 89.9% four weeks ago to 87.7% today (Figure 3a,) with drought retreating or ameliorating from parts of northeast East Texas but expanding and deepening for much of the rest of the state (Figure 3b). Extreme Drought or worse has increased to about 49% of the state, with exceptional drought appearing in splotches that add up to 14% of the state (Figure 3a). In all, 97.1% of the state remains abnormally dry or worse (D0–D4; Figure 3a), up from 96.1% four weeks ago.

Figure 3a: Drought conditions in Texas according to the U.S. Drought Monitor (as of April 12, 2022; source).

Figure 3b: Changes in the U.S. Drought Monitor for Texas between March 15, 2022, and April 12, 2022 (source).

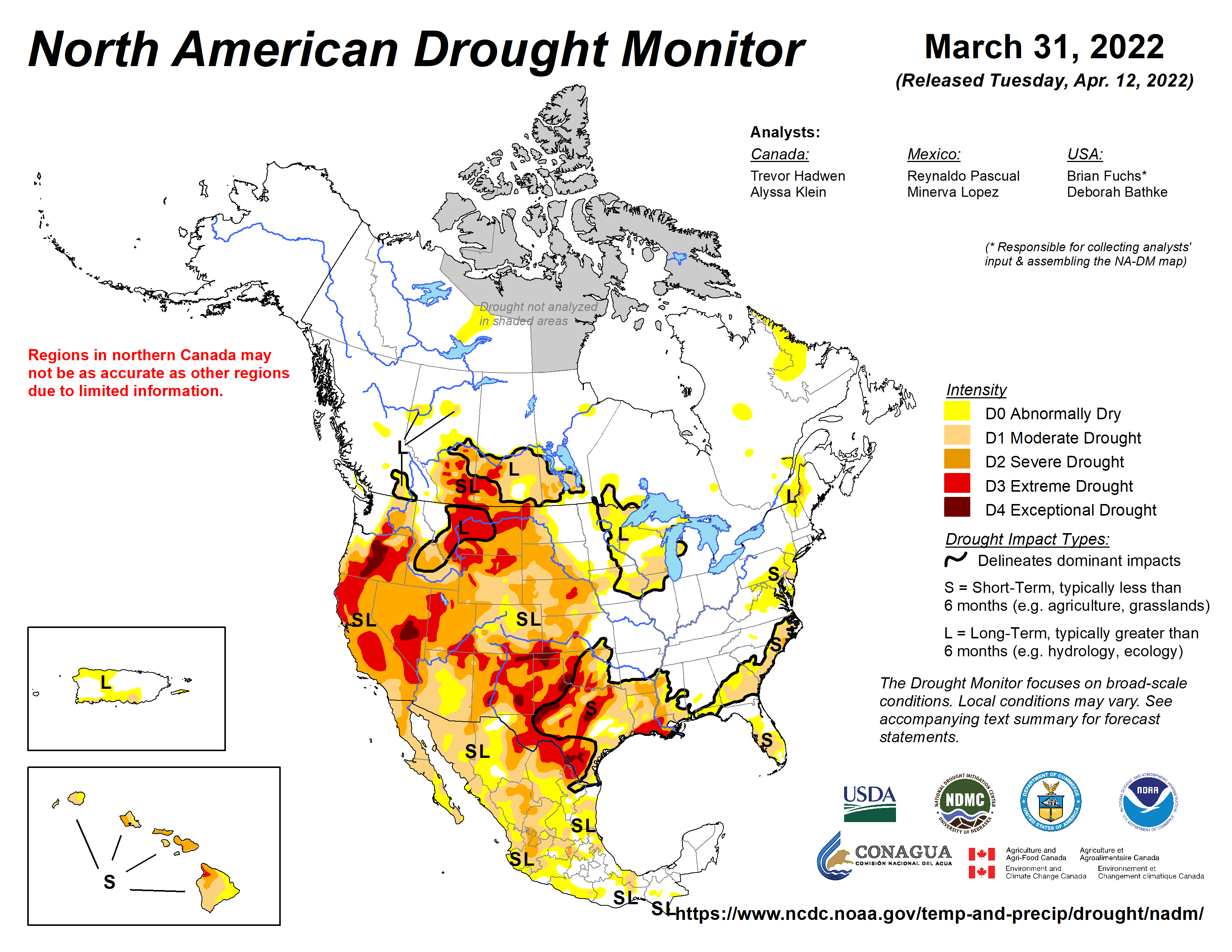

The North American Drought Monitor, which runs a month behind, continues to show drought over much of the western United States, with drought conditions looking similar to those of last month (Figure 4a). Precipitation in the vast majority of the Rio Grande watershed in Colorado and New Mexico over the last 90 days was less than normal, although the watershed in Colorado did see some major precipitation (Figure 4b). You can also see how bad the rainfall deficit is in the Sacramento Mountains of New Mexico in the Ruidoso area, a factor affecting forest fires in the area (Figure 4b).

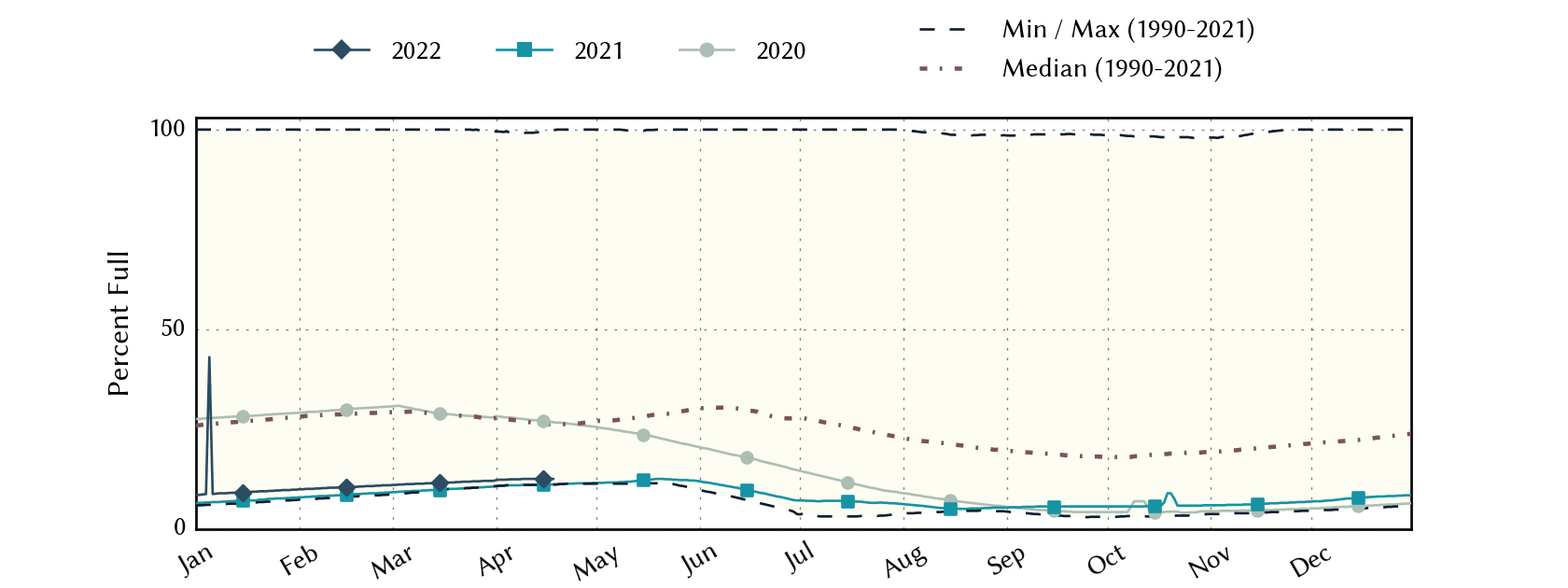

Conservation storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir — an important source of water for the El Paso area — increased from 11.4% full last month to 12.5% today (Figure 4c), just above historic (since 1990) lows.

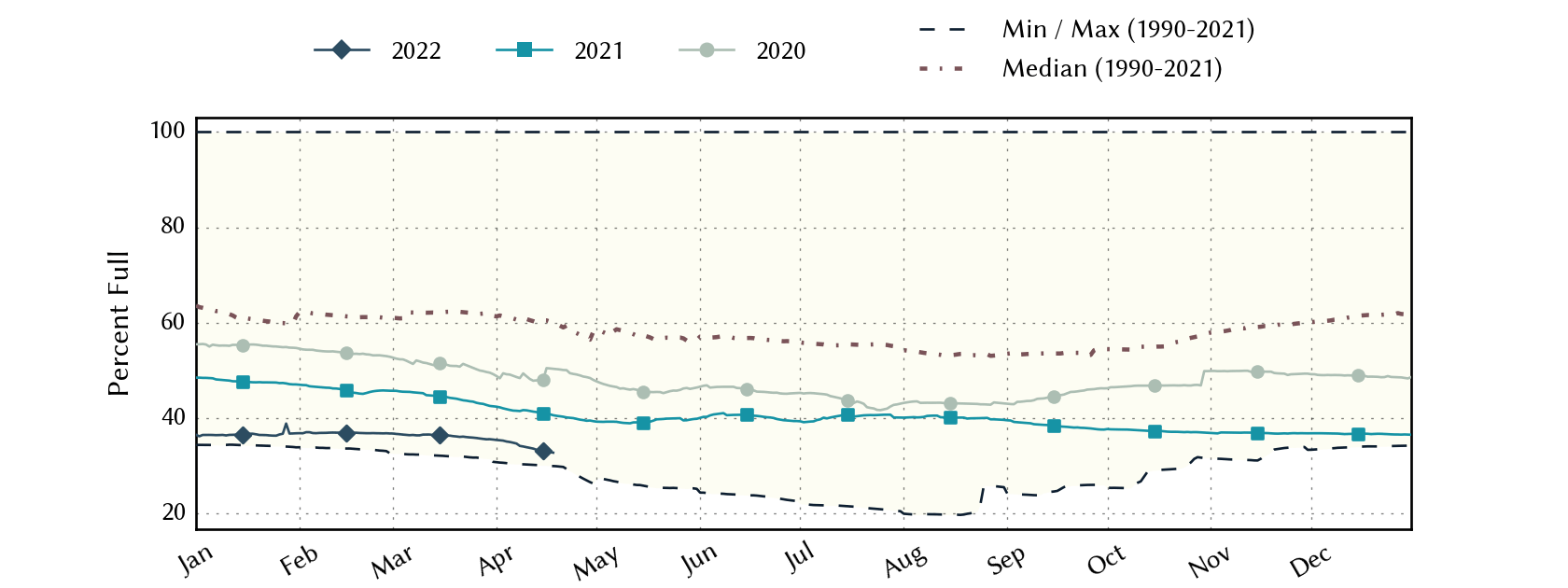

The Rio Conchos Basin in Mexico, which confluences into the Rio Grande just above Presidio and is the largest tributary to the Rio Grande, remains partially abnormally dry in the Sierra Madre Occidental (Figure 4a). Combined conservation storage in the Amistad and Falcon reservoirs decreased from 36.4% last month to 32.7% full today, about 28 percentage points below normal for this time of year (Figure 4d).

Figure 4a: The North American Drought Monitor for March 31, 2021 (source).

Figure 4b: Percent of normal precipitation for Colorado and New Mexico for the 90 days before April 18, 2022 (modified from source). The red line is the Rio Grande Basin. I use this map to see check precipitation trends in the headwaters of the Rio Grande in southern Colorado, the main source of water to Elephant Butte Reservoir downstream.

Figure 4c: Reservoir storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir since 2020 with the median, min, and max for measurements from 1990 through 2021 (graph from Texas Water Development Board).

Figure 4d: Reservoir storage in Amistad and Falcon reservoirs since 2020 with the median, min, and max for measurements from 1990 through 2021 (graph from Texas Water Development Board).

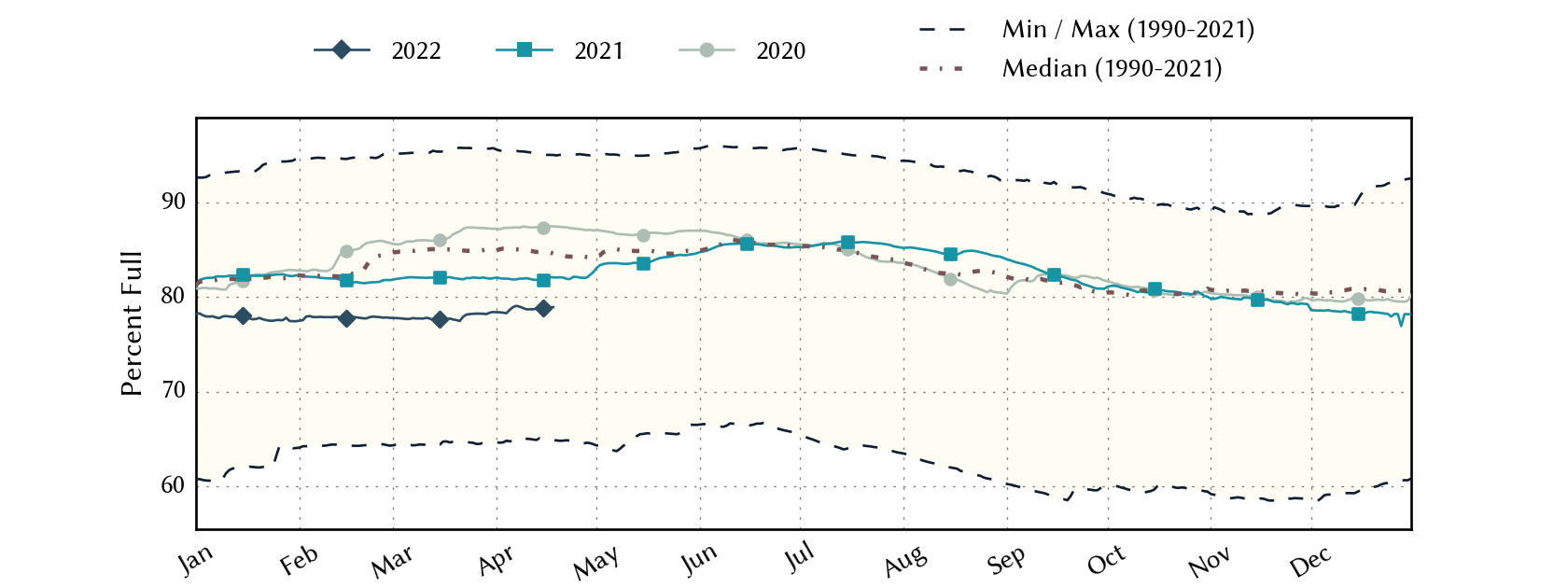

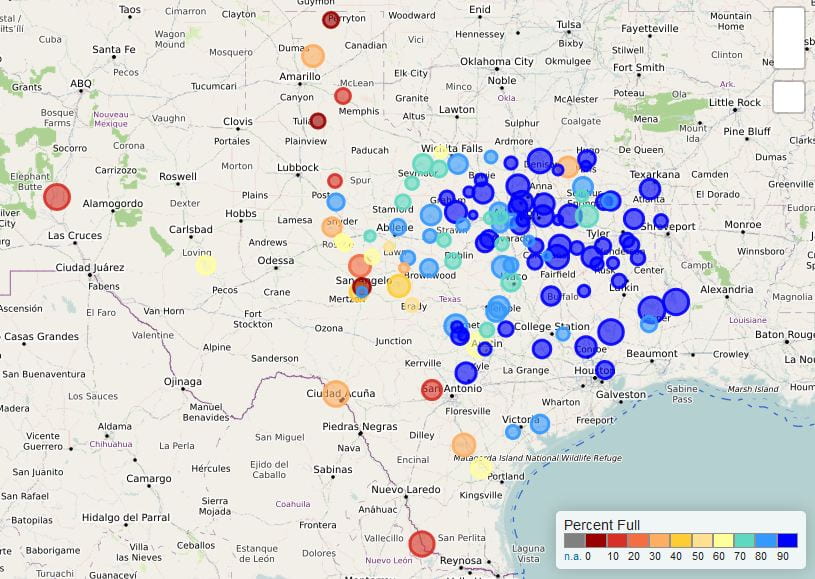

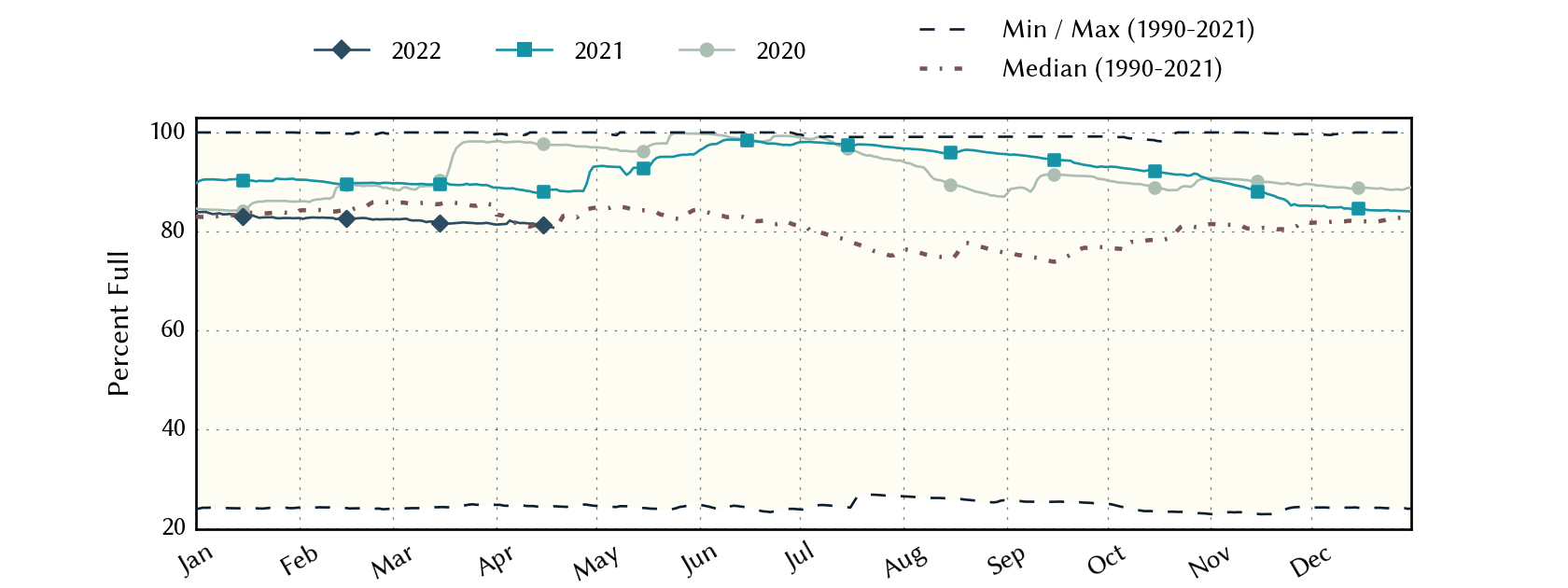

A number of basins across the state have flows over the past week below historical 25th, 10th, and 5th flow percentiles (Figure 5a). Statewide reservoir storage is at 78.9% full as of today, up 414,000 acre-feet from 77.6% a month ago, about five percentage points below normal for this time of year (Figure 5b). Unusual for this time of year, more reservoirs in the eastern part of the state have fallen below 90% and now 80% full (Figure 5c). The “orange” reservoir northeast of Dallas (between 30 and 40% full) is accurately but perhaps unfairly orange since it, Bois D’Arc Lake, is a newborn and just started its initial inundation (Figure 5d).

Figure 5a: Parts of the state with below-25th-percentile seven-day average streamflow as of April 17, 2022 (map modified from U.S. Geological Survey).

Figure 5b: Statewide reservoir storage since 2020 compared to statistics (median, min, and max) for statewide storage from 1990 through 2021 (graph from Texas Water Development Board).

Figure 5c: Reservoir storage as of April 18, 2022 in the major reservoirs of the state (modified from Texas Water Development Board).

Figure 5d: Hydrograph of the month—Reservoir storage for Wichita Falls area reservoirs (Arrowhead, Kemp, Kickapoo; graph from Texas Water Development Board).

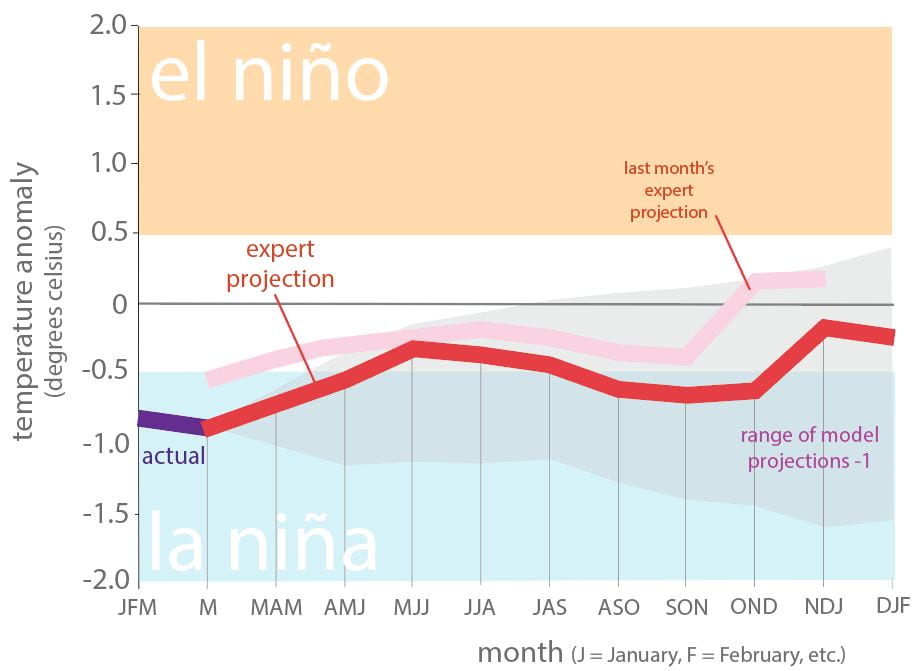

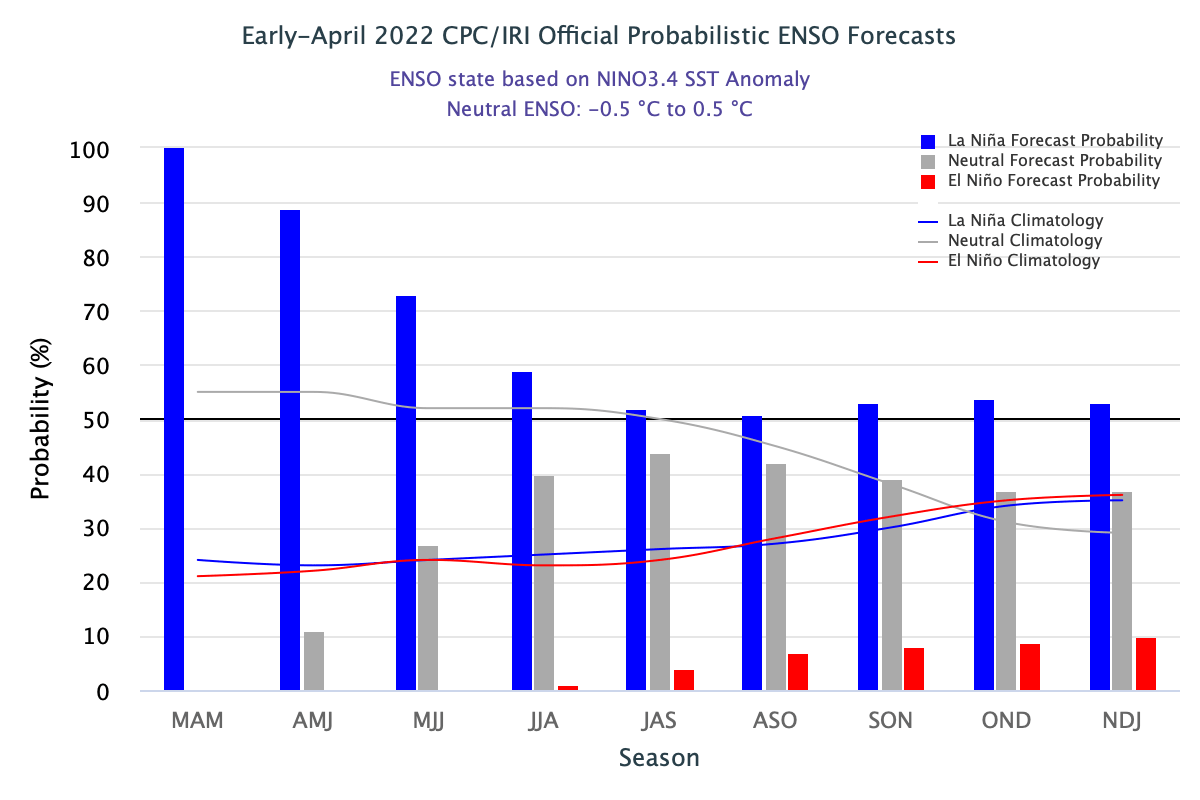

Sea-surface temperatures in the Central Pacific that in part define the status of the El Niño Southern Oscillation continue to reside in La Niña conditions, although they have warmed slightly (Figure 6a). This month’s projection is a bit more pessimistic as far as sea-surface warming is concerned (Figure 6a). Accordingly, we remain under a La Niña Advisory. Projections of sea-surface temperatures suggest a 59% chance of remaining in La Niña conditions through the June-August season with a 50-55% chance of being in La Niña through the fall (Figure 6b).

Figure 6a. Forecasts of sea-surface temperature anomalies for the Niño 3.4 Region as of March 18, 2022 (modified from Climate Prediction Center and others). “Range of model predictions -1” is the range of the various statistical and dynamical models’ projections minus the most outlying upper and lower projections. Sometimes those predictive models get a little craycray!

Figure 6b. Probabilistic forecasts of El Niño, La Niña, and La Nada (neutral) conditions (graph from the Climate Prediction Center and International Research Institute).

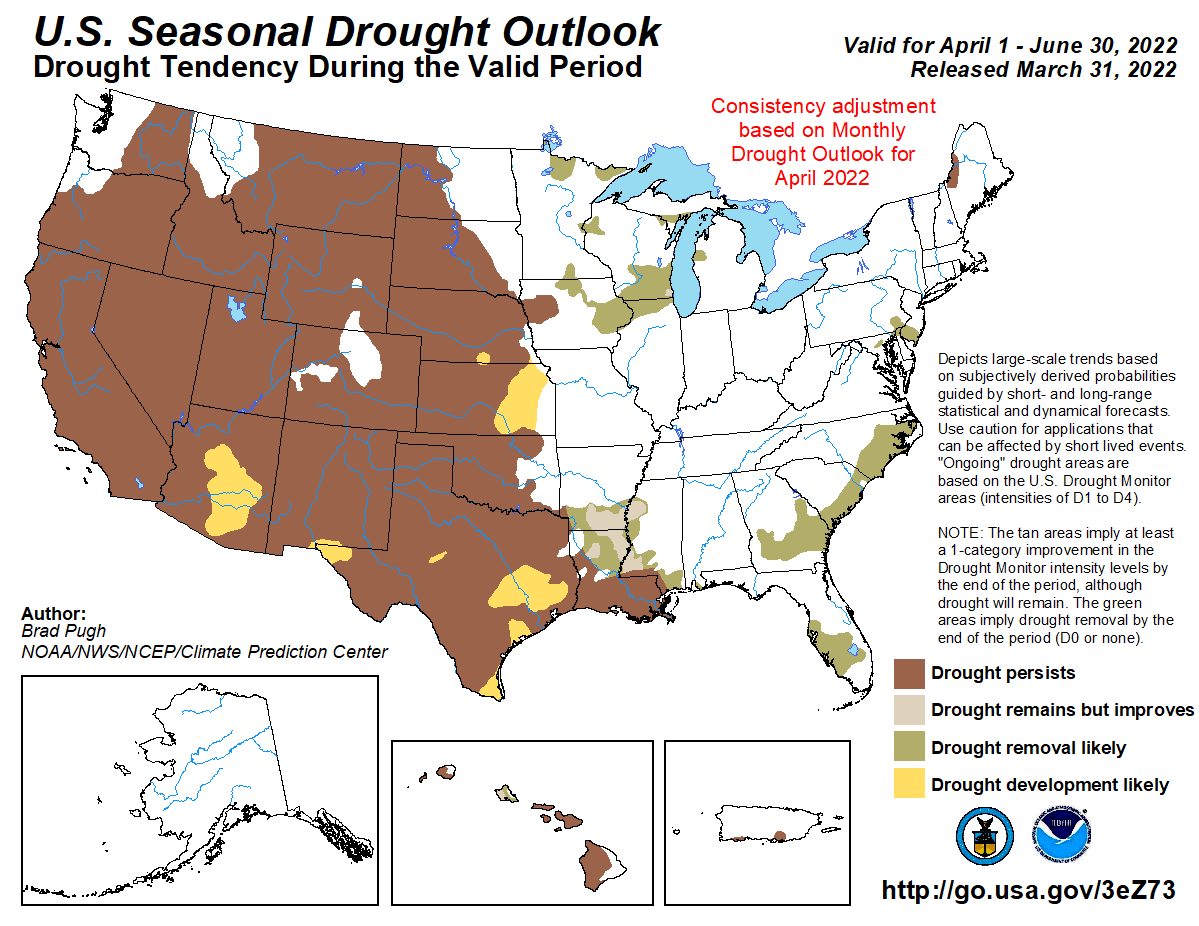

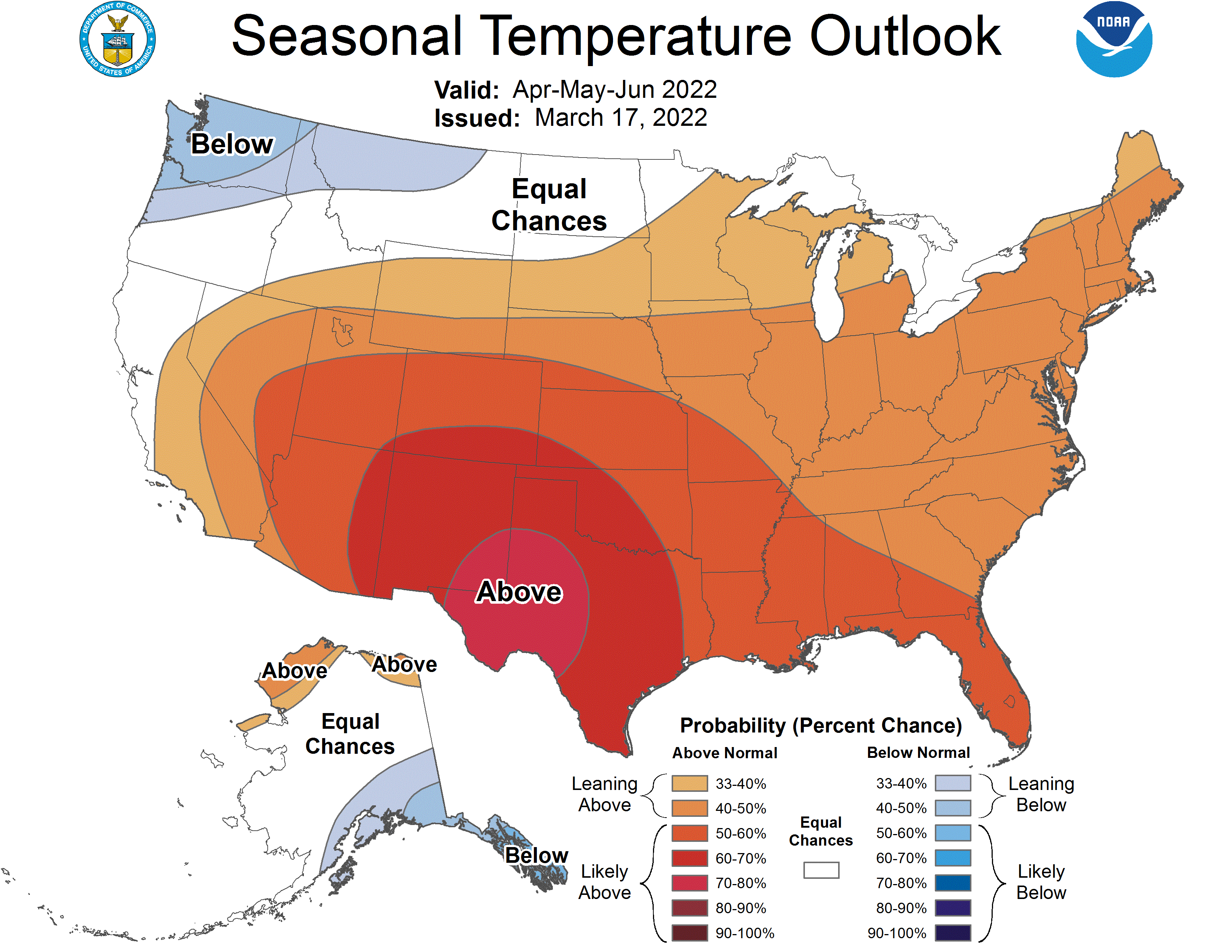

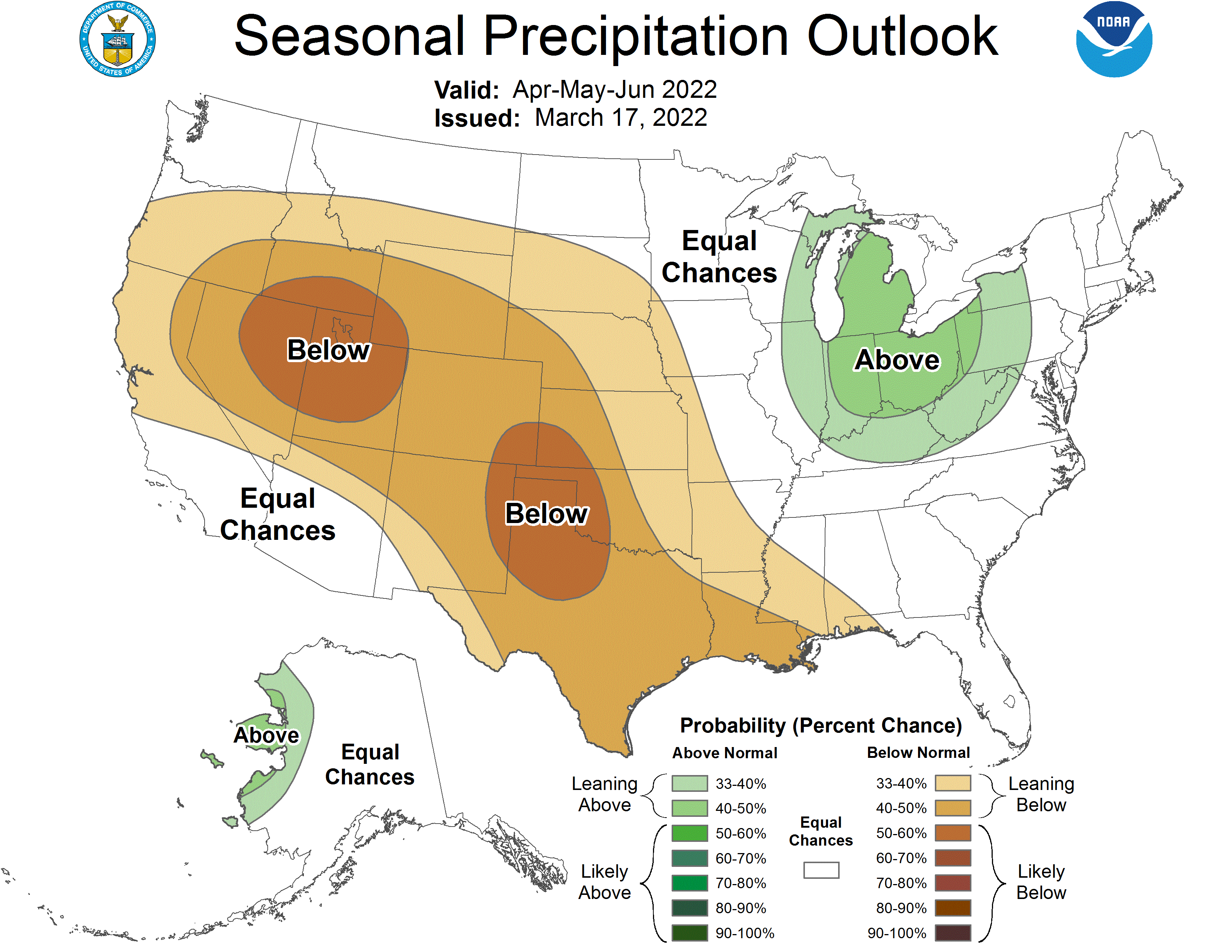

The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook through June 2022 shows the drought retreating somewhat from Arkansas and Louisiana to the Texas border (Figure 7a). Regardless, the drought outlook shows drought continuing or developing for almost the entire state (Figure 7a). The three-month temperature outlook projects warmer-than-normal conditions for the entire state (Figure 7b), while the three-month precipitation outlook favors drier-than-normal conditions for the entire state (Figure 7c).

Figure 7a: The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook for April 1, 2022, through June 30, 2022 (source).

Figure 7b: Three-month temperature outlook for April-May-June 2022 (source).

Figure 7c: Three-month precipitation outlook for April-May-June 2022 (source).