SUMMARY:

- La Niña is no more! Neutral (La Nada) conditions are expected to hold through summer with a 60% chance of El Niño this fall.

- Drought conditions have grown to encompass 64% of the state, with extreme or worse drought conditions intensifying to include 14% of the state.

- Statewide reservoir storage remained about the same at 75% full.

I wrote this article on March 24, 2023.

California has been getting firehosed with atmospheric river after atmospheric river, with the twelfth one hitting the state by March 22. Long, narrow, and wetter than a sheepdog after a dip in Barton Springs, these systems can dump impressive amounts of rain and snow along the West Coast, particularly in California. This spring has been particularly active, with river after river crashing into the coast and, unusually, penetrating the continent, causing large snowfalls as far away as Minnesota.

La Niña tends to push atmospheric rivers, when they occur, up the California coast, but lately, the rivers look like one of those cartoons where Mickey Mouse is on the end of a wildly swinging firehose. There also tends to be fewer atmospheric rivers during La Niñas and more during El Niños, so perhaps the transition from La Niña to neutral conditions played a role. But note my use of the word “tend”— other factors at play, and El Niño-La Niña doesn’t account for them all. With a warming climate, there’s more moisture and energy in the atmosphere, so, as you might have already guessed, scientists expect atmospheric rivers to be more powerful and result in more rain than snow.

Texas isn’t really affected by atmospheric rivers, although we have storm training where an arm of a system feeds a line of storms over a certain location, and we have Flash Flood Alley in the Hill Country. However, we can be affected by leftover moisture (whatever makes it over the mountains) and the general weather patterns that cause the atmospheric rivers. These impacts may increase as the world warms. Dr. Bridget Scanlon with the Bureau of Economic Geology has a study coming out, with funding from the Texas Water Development Board, to look at atmospheric rivers and Texas. I’m sure it will be flooded with good information on this phenomenon.

Figure 1: Atmospheric river fire hosing the West Coast (from here).

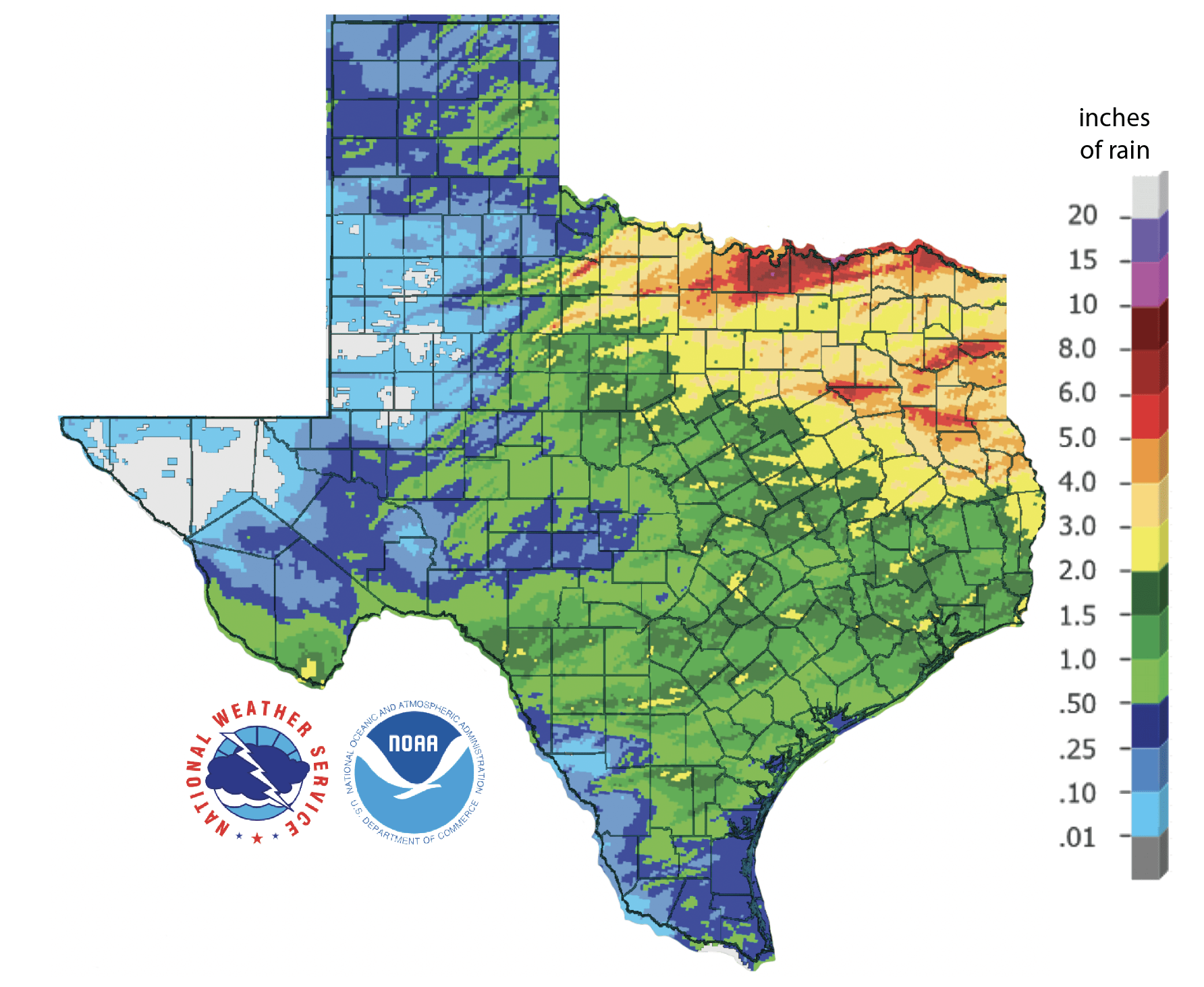

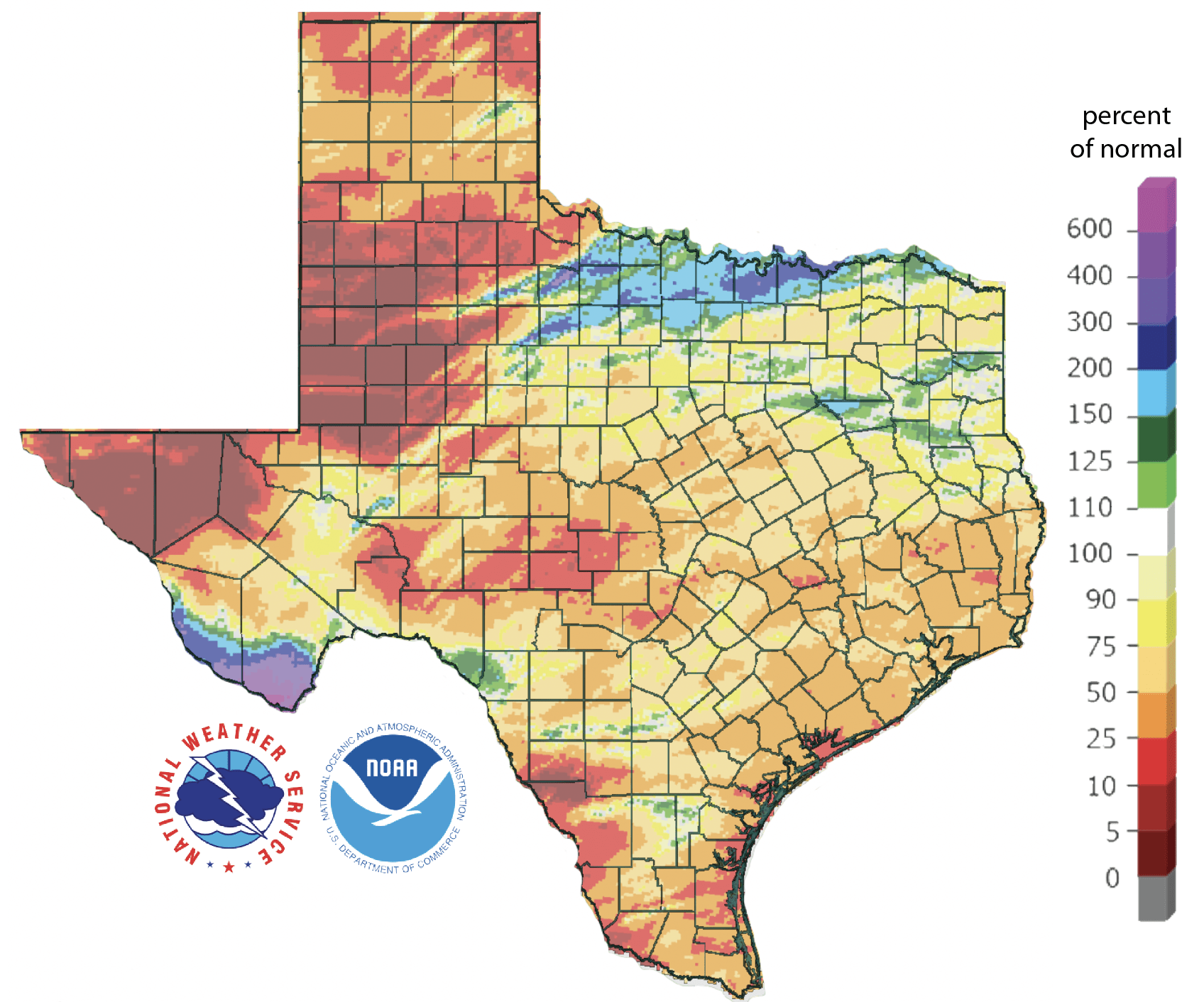

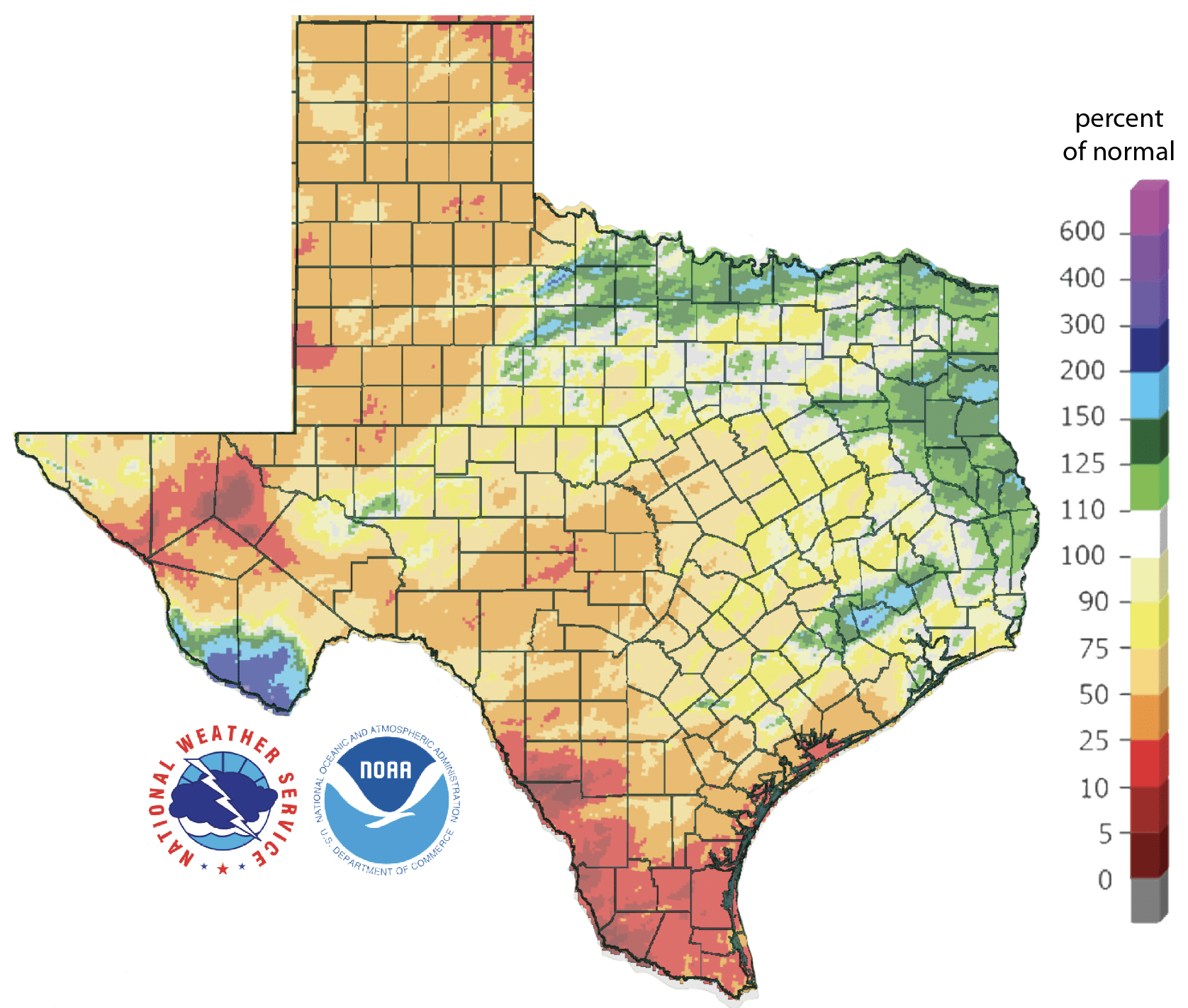

Over the past 30 days, much of the northeastern part of the state saw 2 to 8 inches of rain, while much of the rest saw less than an inch (Figure 2a). That big ole snowfall in the Chisos Mountains shows up! Most of the state saw less than normal rainfall over the past 30 days, with the Big Bend area seeing upwards of four times normal and parts of the Red River seeing 1.5 to two times normal (Figure 2b). Rain over the past 90 days—a big driver for drought conditions—remains below normal for almost the entire state, with large areas in West and Far West Texas receiving less than 25% of normal (Figure 2c).

Figure 2a: Inches of precipitation that fell in Texas in the 30 days before March 24, 2023 (modified from source). Note that cooler colors indicate lower values and warmer indicate higher values. Light grey is no detectable precipitation.

Figure 2b: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the 30 days before March 24, 2023 (modified from source).

Figure 2c: Rainfall as a percent of normal for the 90 days before March 24, 2023 (modified from source).

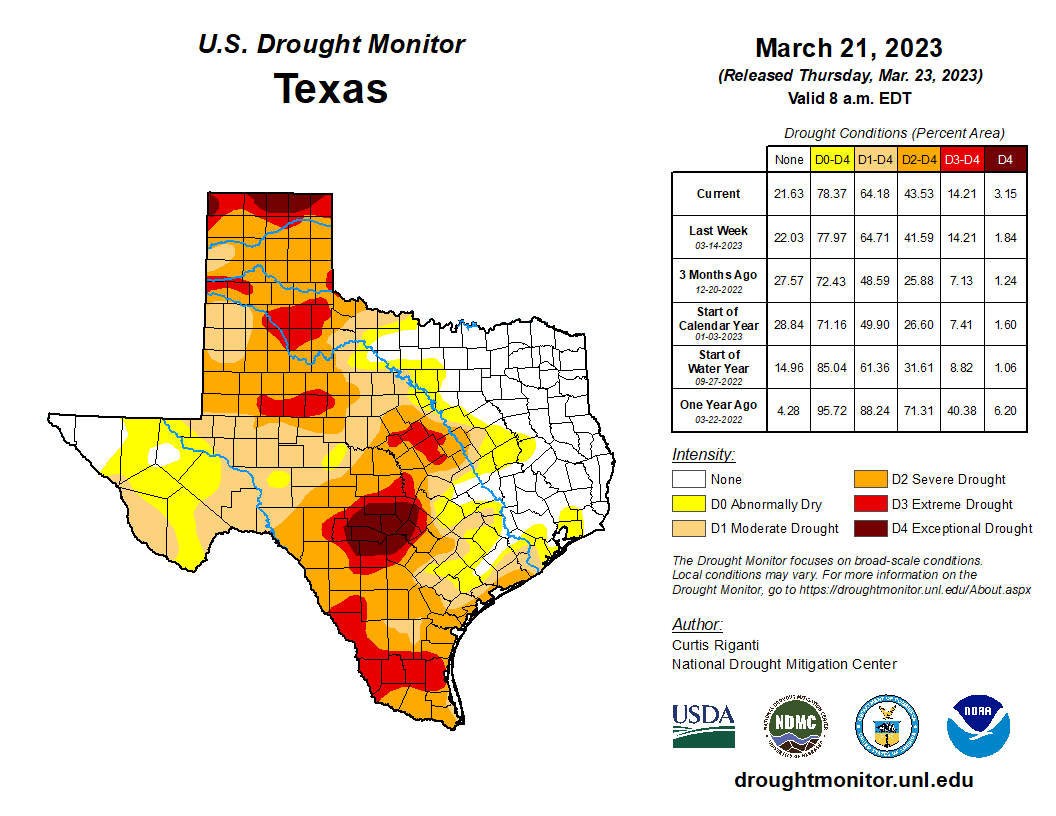

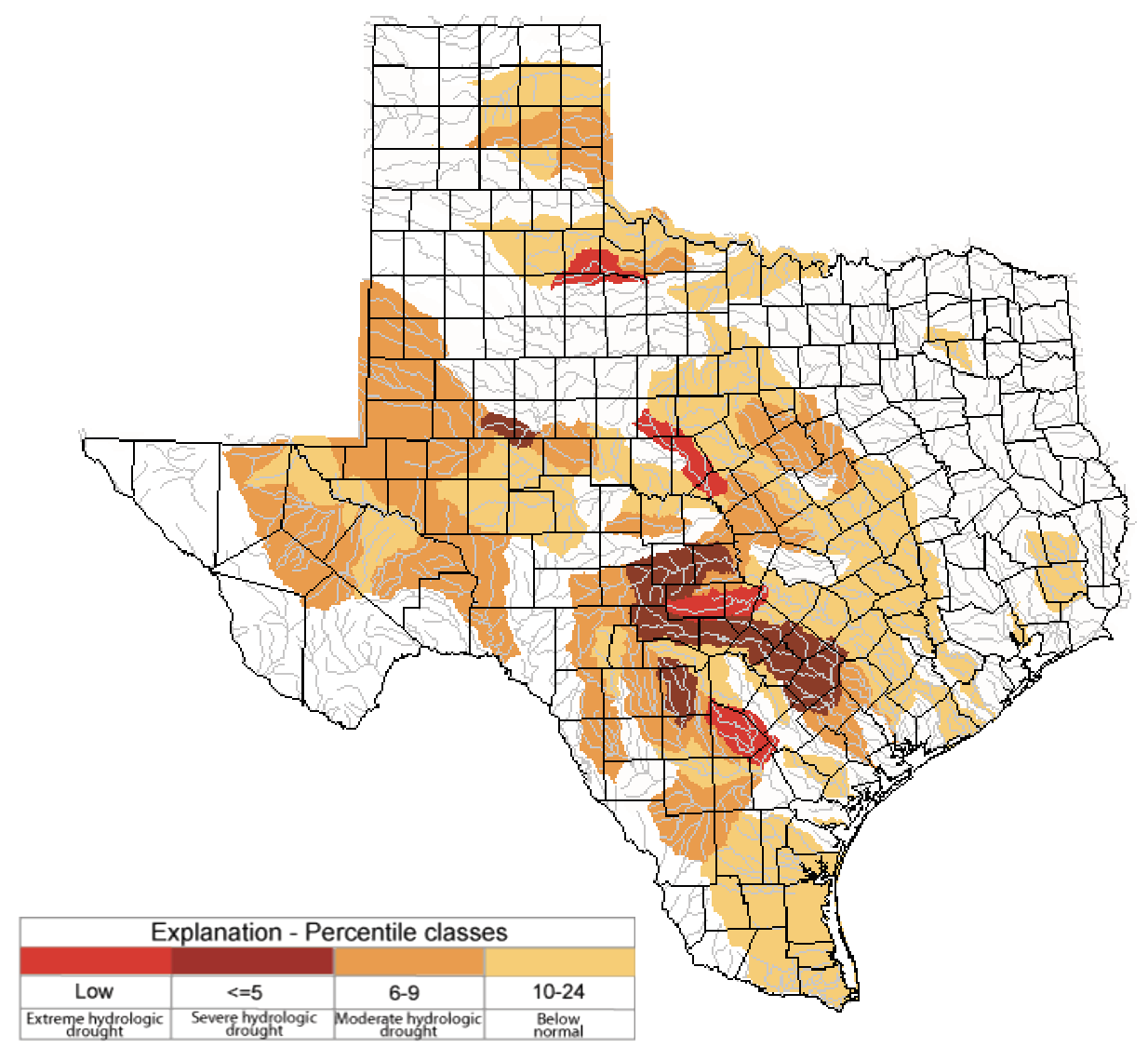

The amount of the state under drought conditions (D1–D4) increased from 58% four weeks ago to 64% now (Figure 3a), with drought intensity decreasing in north-central Texas but intensifying in the southwestern half of the state (Figure 3b). Extreme drought, or worse, has increased from 10% of the state four weeks ago to 14%, with exceptional drought increasing from 1.8% to 3.2% (Figure 3a). In all, 78% of the state remains abnormally dry or worse (D0–D4; Figure 3a), up slightly from 77% four weeks ago.

Figure 3a: Drought conditions in Texas according to the U.S. Drought Monitor (as of March 21, 2023; source).

Figure 3b: Changes in the U.S. Drought Monitor for Texas between February 21, 2023, and March 21, 2023 (source).

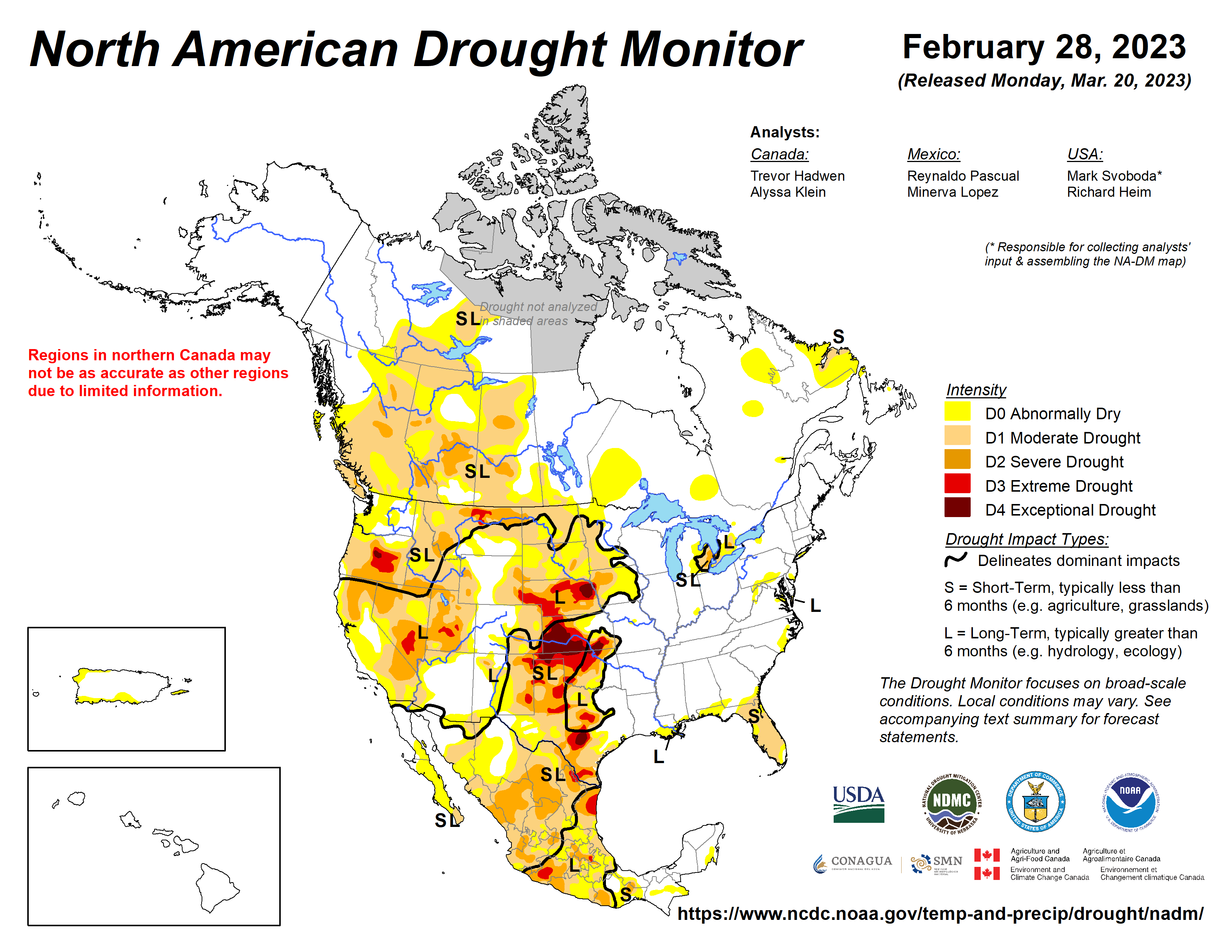

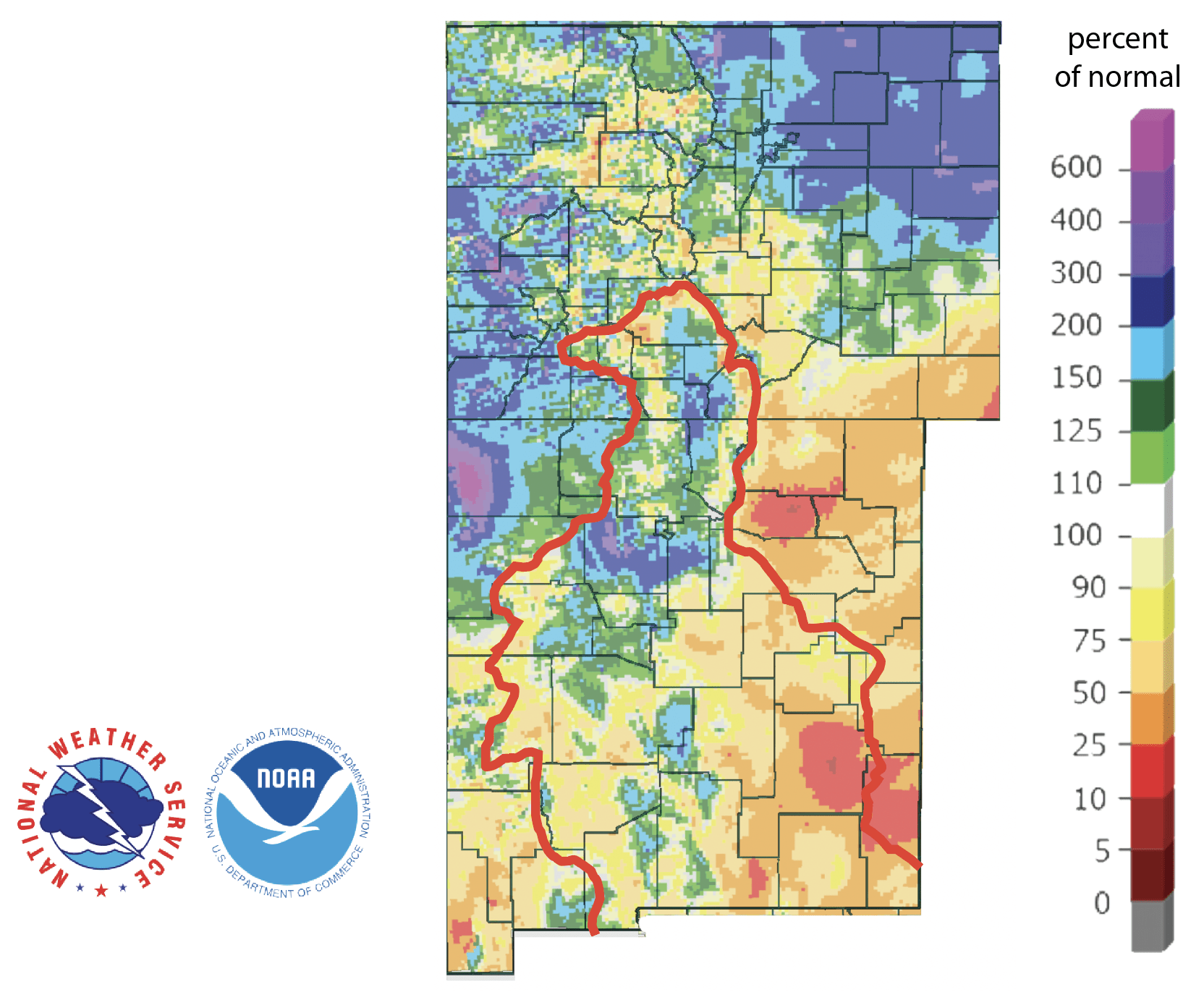

The North American Drought Monitor, which runs a month behind, shows drought over much of the western United States and Mexico (Figure 4a). Precipitation over much of the Rio Grande watershed in Colorado and New Mexico over the last 90 days was lower than normal, but there were areas with more than 1.5 times normal precipitation (Figure 4b).

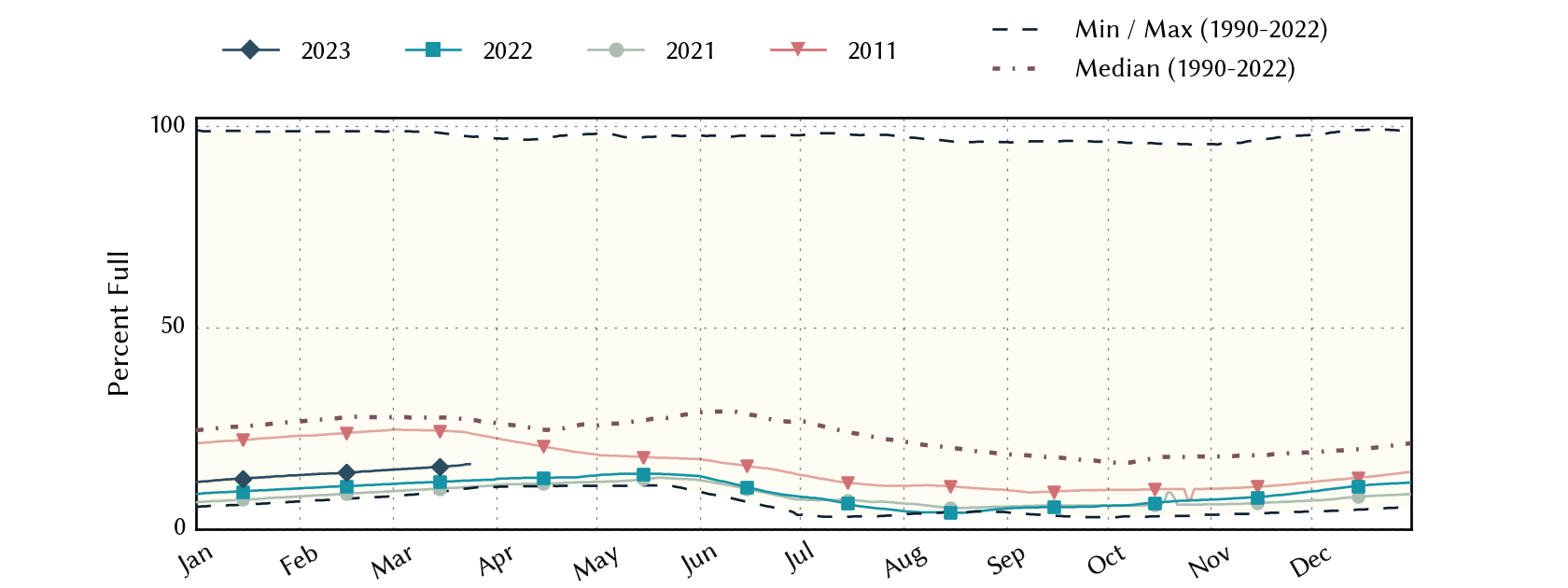

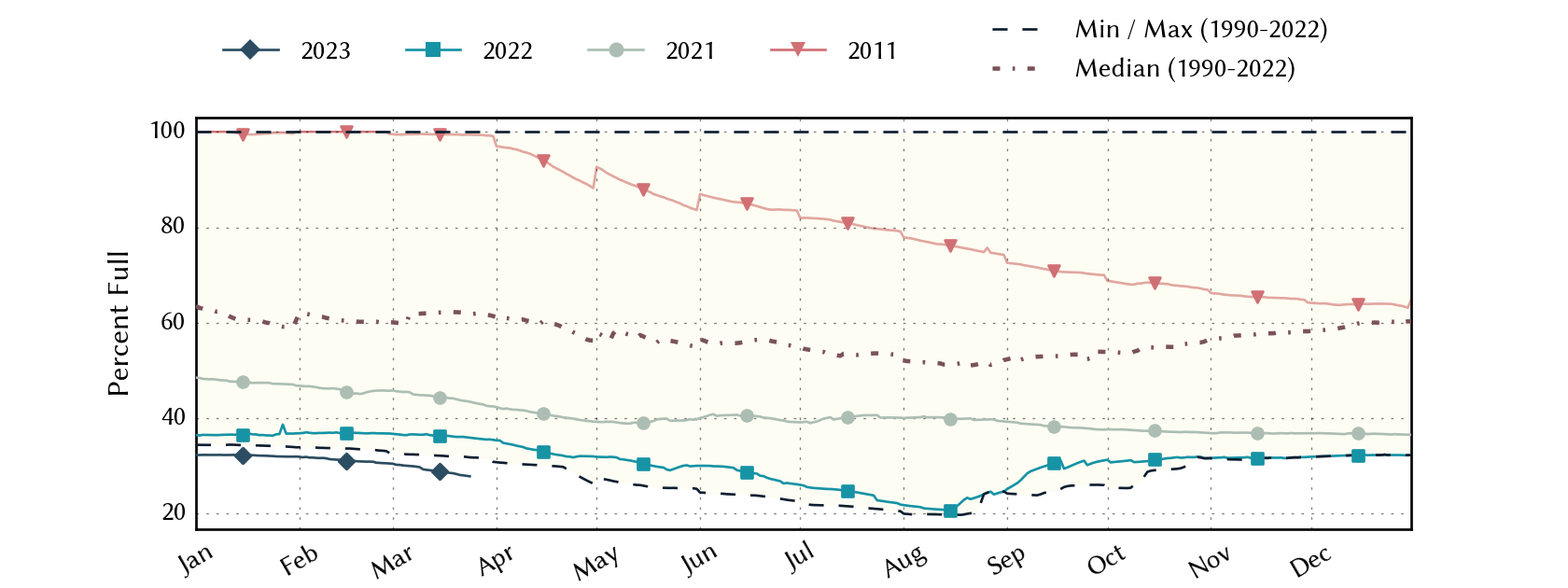

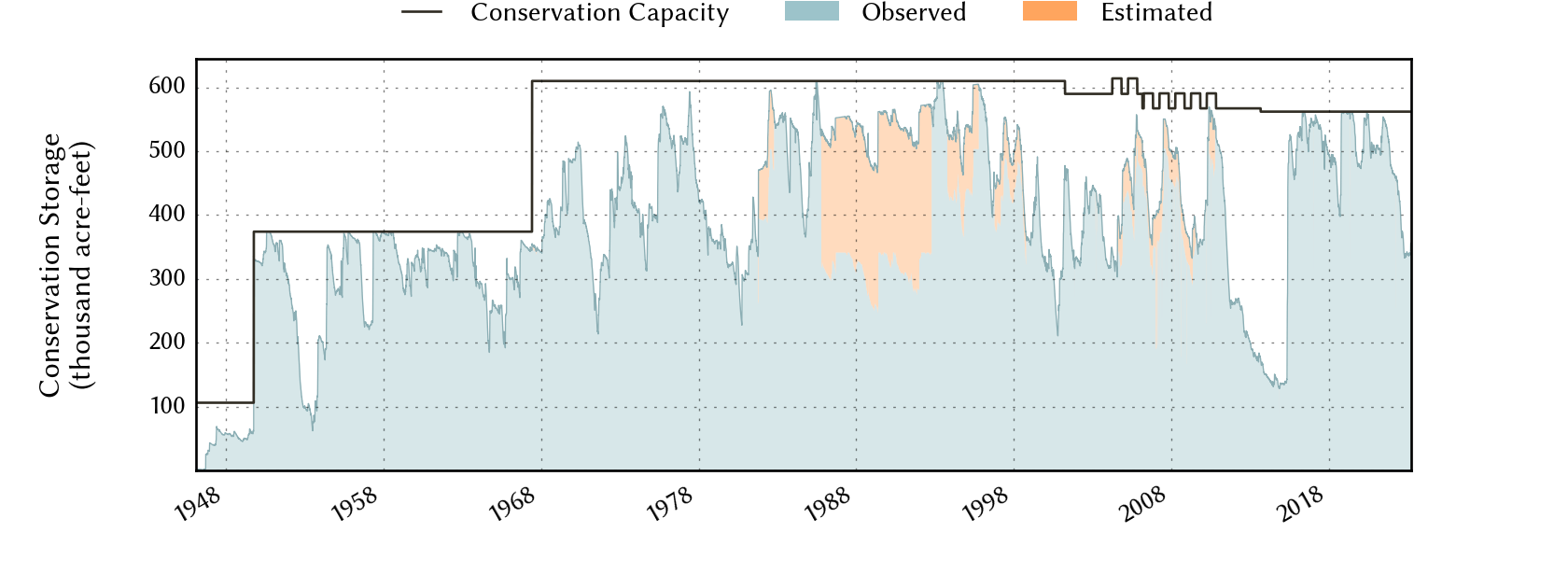

Conservation storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir—an important source of water for the El Paso area—increased to 15.9% full from 14.3% four weeks ago (Figure 4c), slightly above historic (since 1990) lows.

The Rio Conchos basin in Mexico, which confluences with the Rio Grande just above Presidio and is the largest tributary to the Lower Rio Grande, remains abnormally dry (Figure 4a). Combined conservation storage in the Amistad and Falcon reservoirs decreased to 27.8% full from 30.6% four weeks ago, about 32 percentage points below normal for this time of year and below the lowest low for this time of year recorded since 1990 (Figure 4d).

Figure 4a: The North American Drought Monitor for February 28, 2022 (source).

Figure 4b: Percent of normal precipitation for Colorado and New Mexico for the 90 days before March 24, 2023 (modified from source). The red line is the Rio Grande Basin. I use this map to see check precipitation trends in the headwaters of the Rio Grande in southern Colorado, the main source of water to Elephant Butte Reservoir downstream.

Figure 4c: Reservoir storage in Elephant Butte Reservoir since 2021 with the median, min, and max for measurements from 1990 through 2022 (graph from Texas Water Development Board).

Figure 4d: Reservoir storage in Amistad and Falcon reservoirs since 2021 with the median, min, and max for measurements from 1990 through 2022 (graph from Texas Water Development Board).

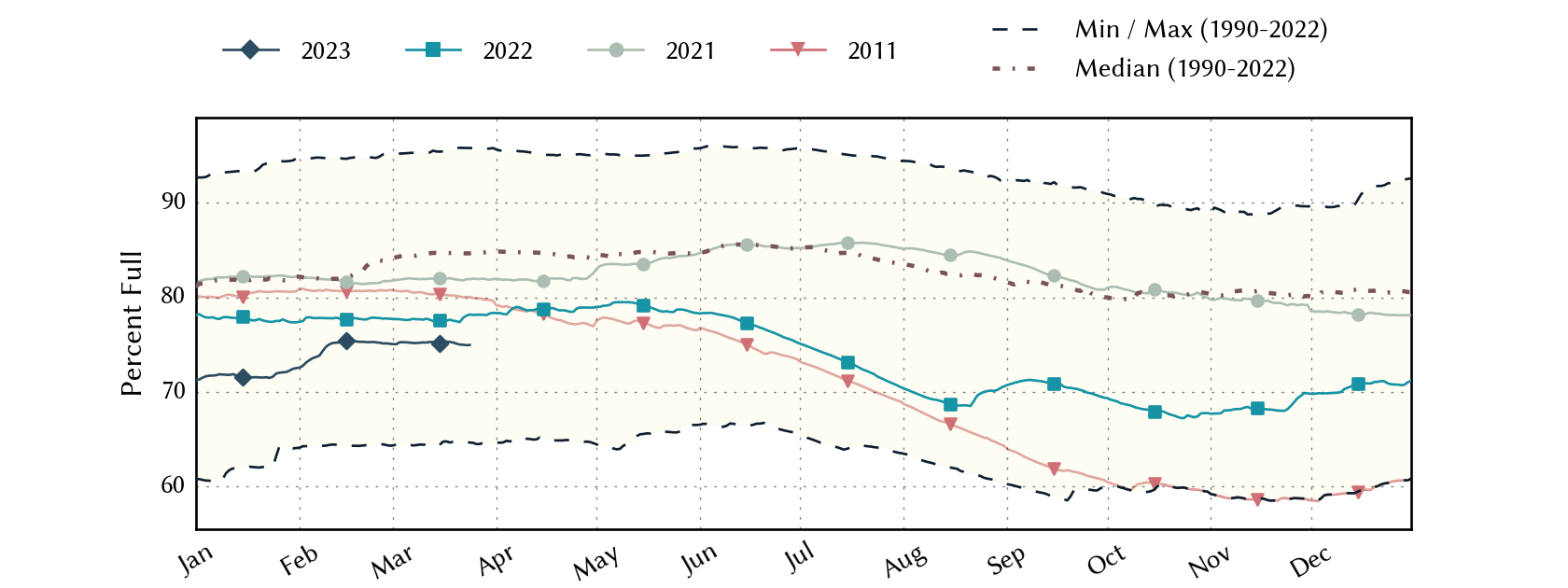

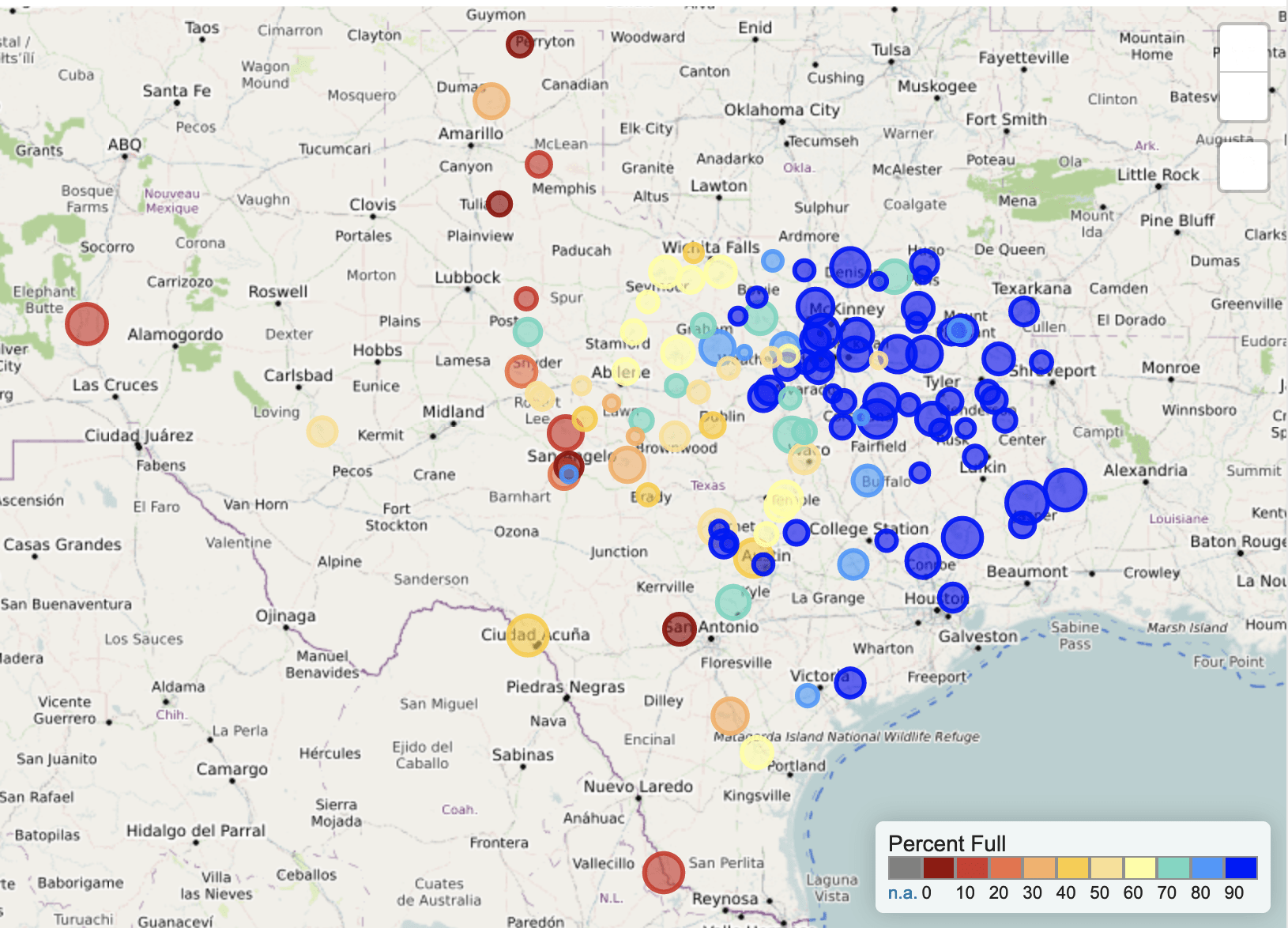

Basins across the state continue to have flows over the past week below historical 25th, 10th, and 5th flow percentiles (Figure 5a). Statewide reservoir storage is at 75% full as of February 26, down about 63 thousand acre-feet from 75.2% four weeks ago and now about 10 percentage points below normal for this time of year (Figure 5b). Several reservoirs in the eastern part of the state have recovered to more than 90% full, with just a few less than 90% full (Figure 5c). The “light blue” reservoir northeast of Dallas (between 70 and 80% full) is accurately but perhaps unfairly that color since it, Bois D’Arc Lake, is a relative newborn and just started its initial inundation last year (Figure 5c). Reservoirs in the Wichita Falls area are down to 63.4% full, about 20 percentage points below normal for this time of year (Figure 5d).

Figure 5a: Parts of the state with below-25th-percentile seven-day average streamflow as of March 23, 2023 (map modified from U.S. Geological Survey).

Figure 5b: Statewide reservoir storage since 2021 compared to statistics (median, min, and max) for statewide storage from 1990 through 2022 (graph from Texas Water Development Board).

Figure 5c: Reservoir storage as of March 24, 2023, in the major reservoirs of the state (modified from Texas Water Development Board).

Figure 5d: Hydrograph Of The Month—Reservoir storage for Choke Canyon Reservoir (graph from Texas Water Development Board).

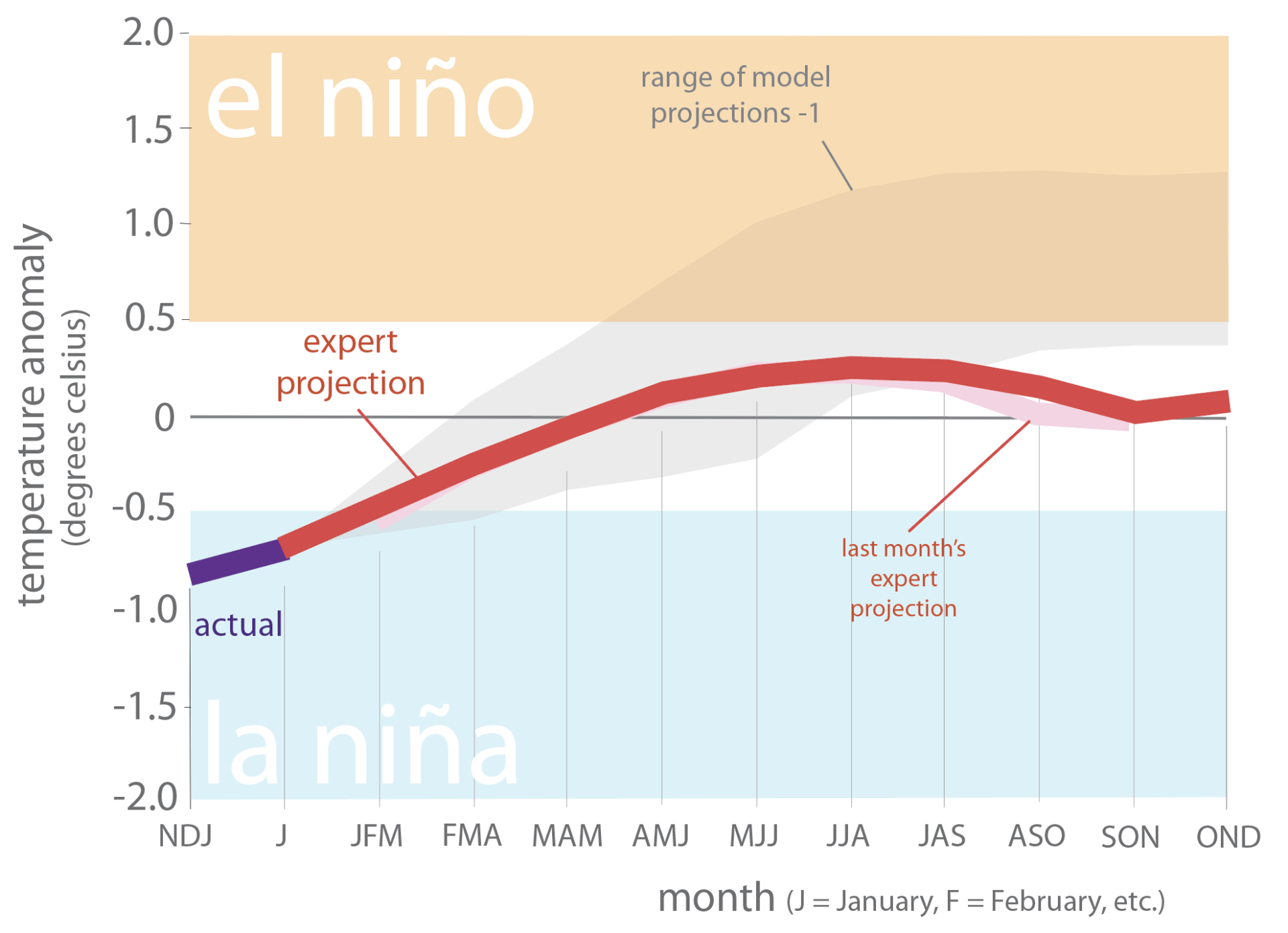

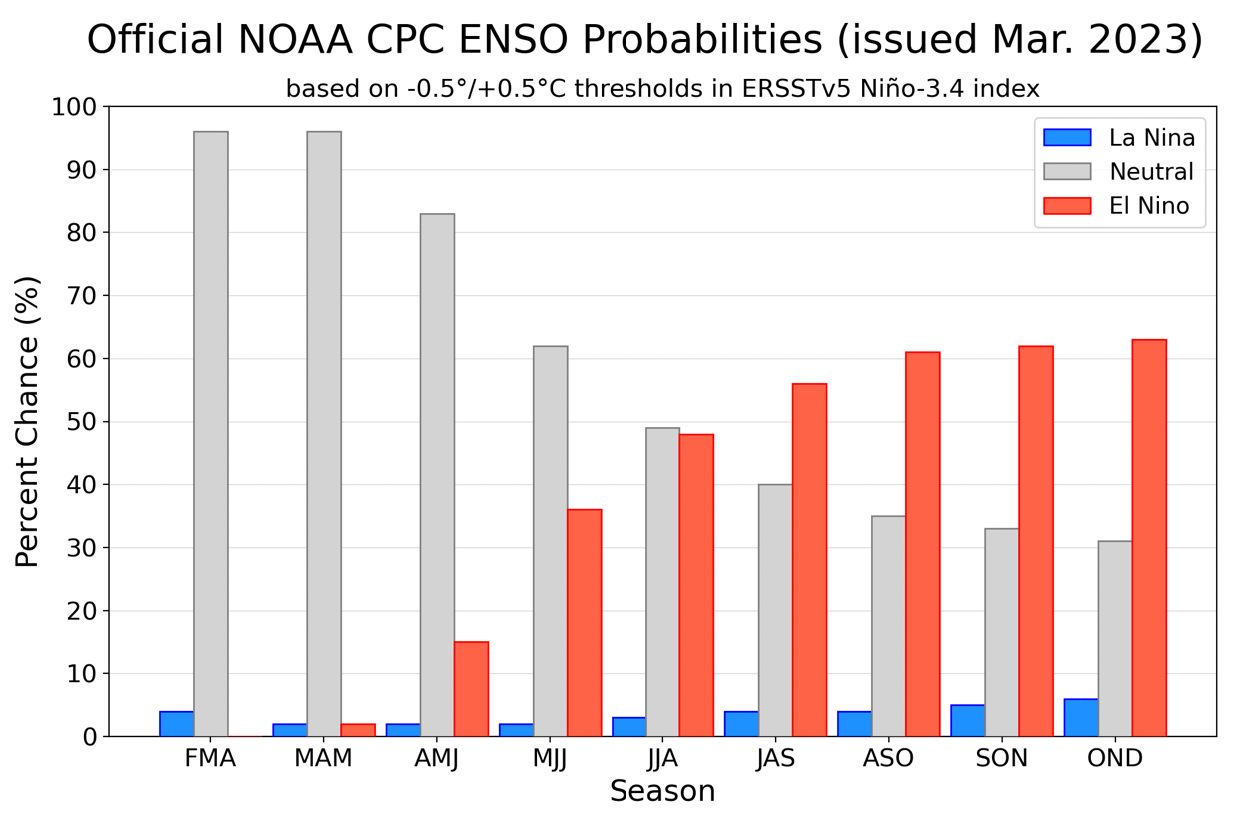

Sea-surface temperatures in the Central Pacific that, in part, define the status of the El Niño Southern Oscillation now reside in neutral conditions, thus indicating the end of La Niña conditions (Figure 6a). This month’s expert (consolidated) projection diverges from the plume of models, suggesting neutral conditions through much of the year (Figure 6a). However, the official probabilities, a month newer than the model projections, favor (with a 60% chance) El Niño development in the fall (Figure 6b).

Figure 6a. Forecasts of sea-surface temperature anomalies for the Niño 3.4 Region as of February 20, 2023 (modified from Climate Prediction Center and others). “Range of model predictions -1” is the range of the various statistical and dynamical models’ projections minus the most outlying upper and lower projections. Sometimes those predictive models get a little craycray.

Figure 6b. Probabilistic forecasts of El Niño, La Niña, and La Nada (neutral) conditions (graph from Climate Prediction Center and others).

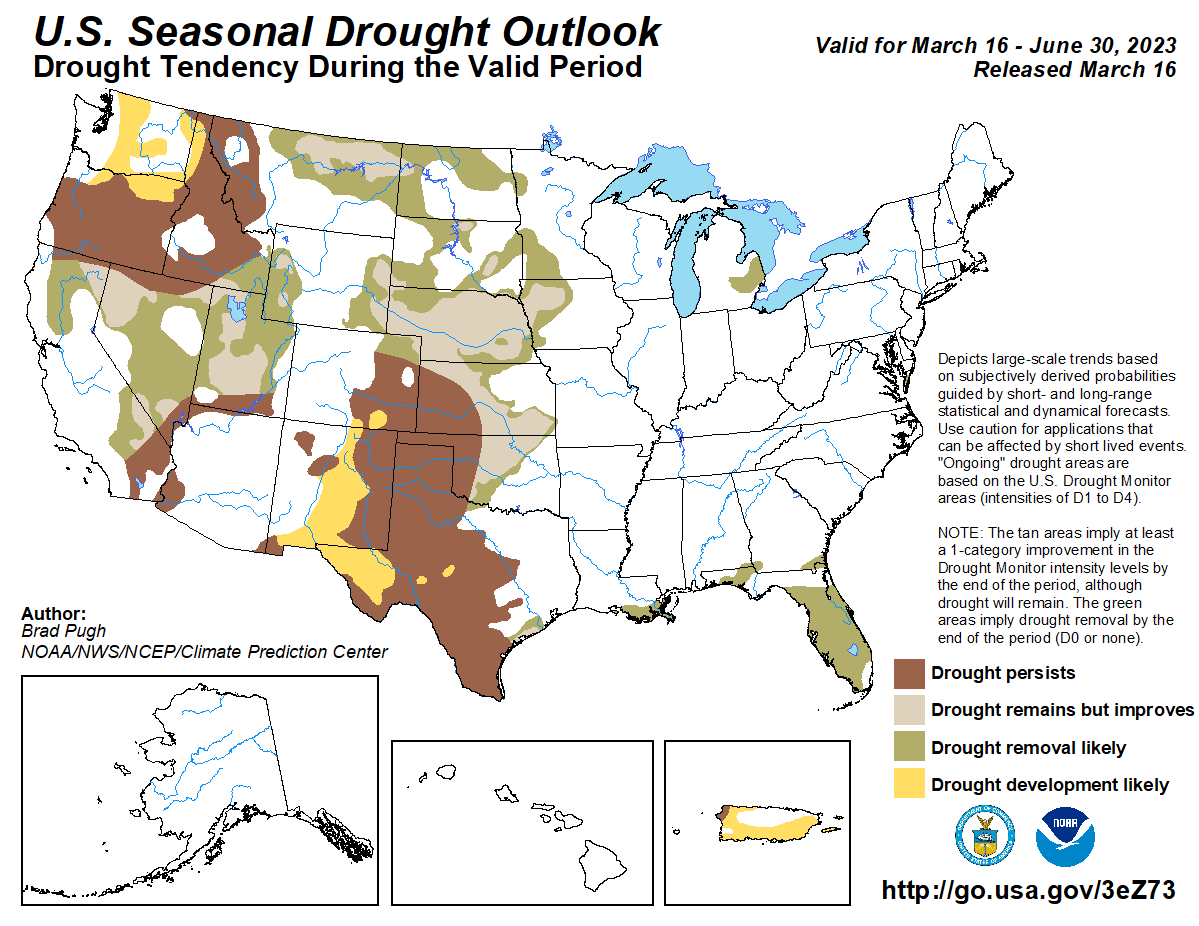

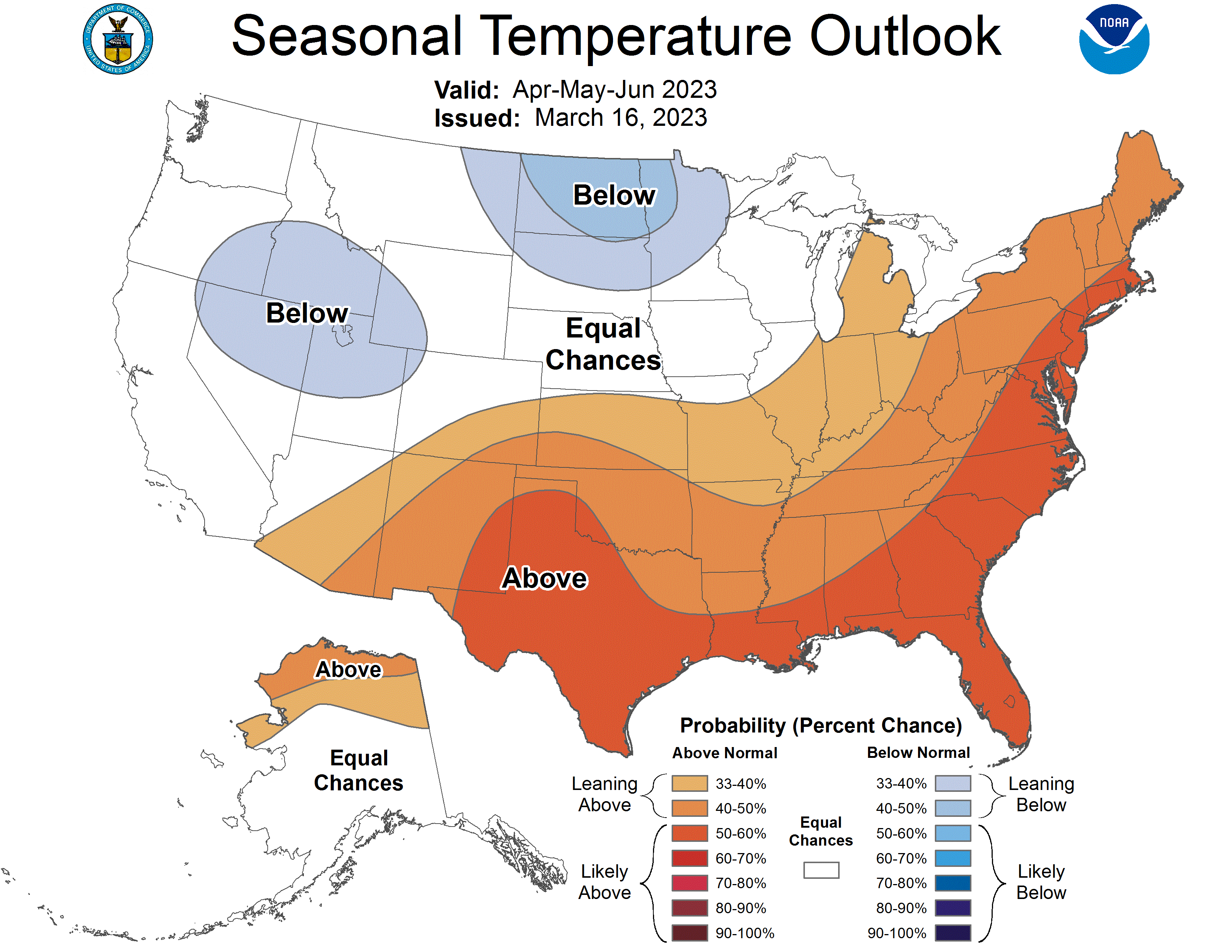

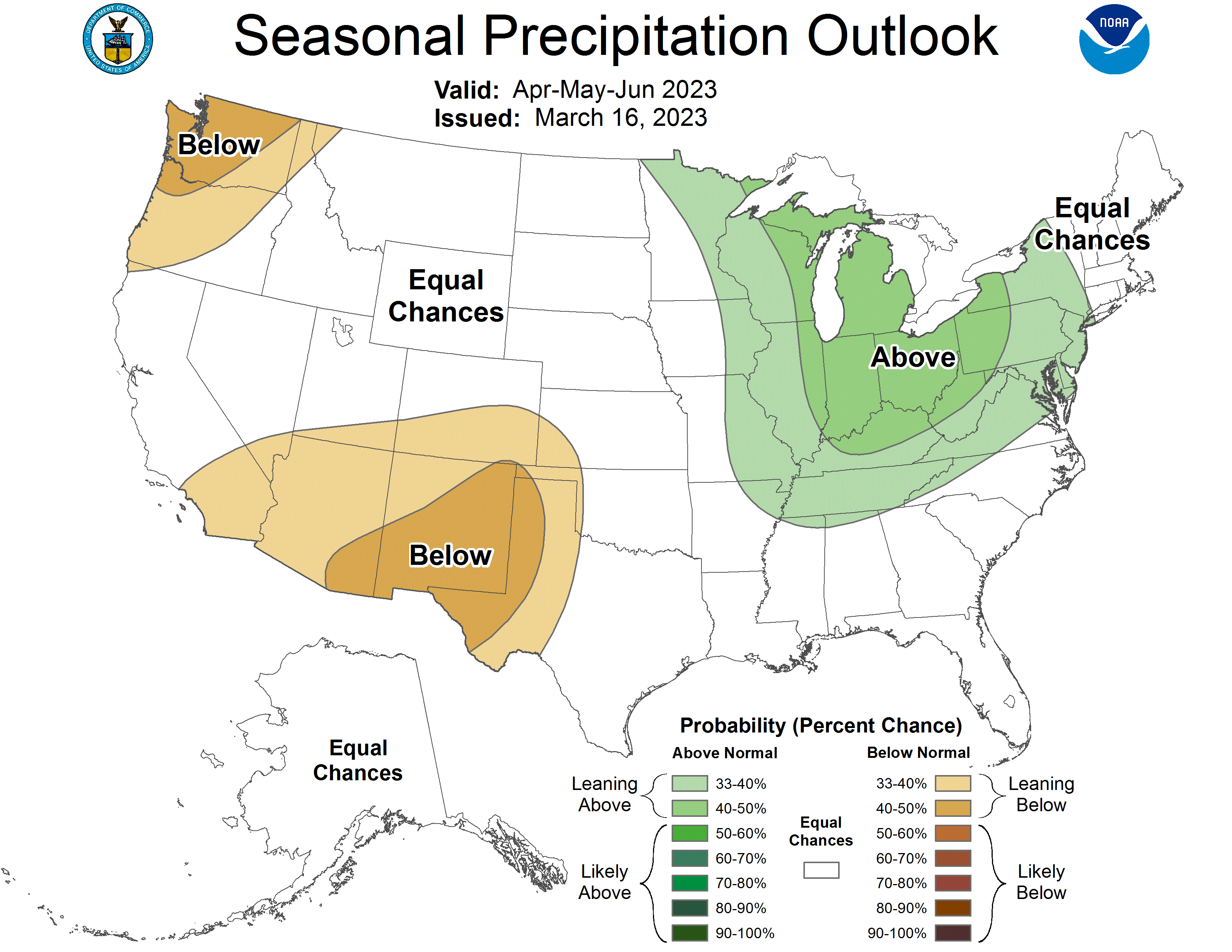

The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook through June 2023 shows drought persisting and developing over much of the western two-thirds of the state (Figure 7a). Like a broken record, the three-month temperature outlook projects warmer-than-normal conditions for all of the state (Figure 7b), while the three-month precipitation outlook favors drier-than-normal conditions for the westernmost part of the state (Figure 7c).

Figure 7a: The U.S. Seasonal Drought Outlook for March 16, 2023, through June 30, 2023 (source).

Figure 7b: Three-month temperature outlook for April-May-June 2023 (source).

Figure 7c: Three-month precipitation outlook for April-May-June 2023 (source).