With 38 public universities and 35 private colleges and universities in the state and many more across the country (and the world) interested in Texas, there’s a great deal of academic scholarship focused on water in the Lone Star State. In this column, I provide brief summaries to several recent academic publications on water in Texas.

Let’s start thinking about water!

Optimizing Water Supply Through Reservoir Conversion and Storage of Return Flow—a Case Study at Joe Pool Lake

Joe Pool Lake. Photo Credit: Jaymzyates, Wikimedia Commons

Many reservoirs in Texas (51 of them built between 1901 and 1991) were built for flood control or include storage capacity for flood. As the state grows and droughts occur, water planners wonder about converting flood storage into conservation storage to meet current and future demands for water. Sekar and collaborators used mixed integer linear programming to investigate tradeoffs between capturing and storing runoff versus return flow in Joe Pool Lake. Their methodology showed that converting flood pool to water supply was not cost effective because conversion costs (assumed at $88.82 per acre-foot) is high compared to potential revenue resulting in a 170-year payback. When they analyzed what conversion costs needed to be to break even, they came up with $20 per acre-foot.

Citation

Sekar, S., Daghighi, A., Chen, V.C.P., Clingenpeel, G., Zhang, Y., Rosenberger, J.M., and Boskabadi, A., 2022, Optimizing water supply through reservoir conversion and storage of return flow—A case study at Joe Pool Lake: Texas Water Journal, v. 13, n. 1, p. 1-12. https://twj-ojs-tdl.tdl.org/twj/index.php/twj/article/view/7124

Health Disparities and Climate Change—the Intersection of Three Disaster Events on Vulnerable Communities in Houston, Texas

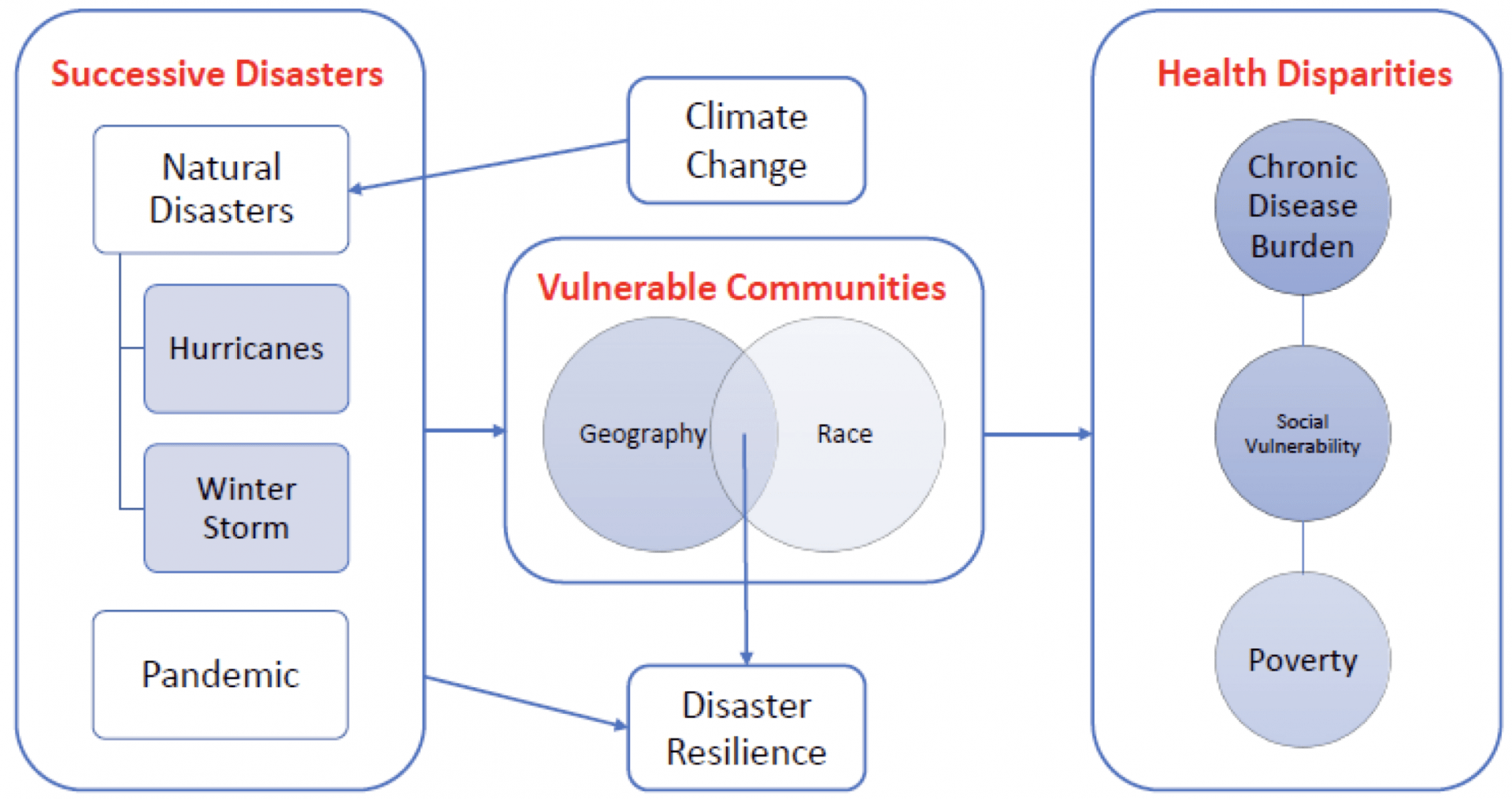

Conceptual Framework depicting the hypothesized relationships between successive disasters (and role of climate change), population geography and race, and health disparities related outcomes.

Harris County, home of Houston, is the United States’ fourth most populous county. Sixty percent of Harris County’s population identifies as Hispanic or Black, folks who are twice as likely to live below the poverty line as compared to white and Asian residents. Adepoju and co-authors used Hurricane Harvey, Winter Storm Uri, and the COVID-19 pandemic to assess disaster exposure in minority communities in the county. Using quantitative (geographic) and qualitative (focus-group interviews) methods, the authors investigated the relationship between the different disasters. They identified four predominantly non-Hispanic Black communities and found significantly greater flooding and significantly greater exposure to COVID-19 risk factors compared to the rest of Harris County. Hospitalizations for non-Hispanic Black people are 4.7 times higher than for white people, while deaths are 2.1 times higher. Amidst the bad news of the asymmetric impacts from natural disasters is a glimmer of positivity in that prior disasters increased the resiliency of communities to subsequent disasters.

Citation

Adepoju, O.E., Han, D., Chae, M., Smith, K.L., Gilbert, L., Choudhury, S., and Woodard, L., 2022, Health disparities and climate change—The intersection of three disaster events on vulnerable communities in Houston, Texas: International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, v. 19, no. 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19010035

Center Pivot Irrigation Capacity Effects on Maize Yield and Profitability in the Texas High Plains

Texas Corn Field. Photo credit: Daniel – stock.adobe.com

As saturated thicknesses decline in the Ogallala Aquifer, the productivity of irrigation wells declines as well. Folks can infill with additional wells to make up for production losses, but at some point the economics of that dry up, leaving farmers with decisions on how to manage their limited water resources. This situation, commonly referred to as deficit irrigation, means that farmers can no longer produce as much water as they want. Do they use the water they can produce along with rainfall to produce a full crop with some risk of crop failure due the fickleness of Mother Nature? Or should they decrease what they irrigate to focus on growing smaller acres of irrigated crops with no risk of failure (at least from lack of water)? Domínguez and co-authors look at this issue for corn using the MOPECO crop model for center pivot irrigation. First, they found that pre-watering had no impact on crop yield if a producer has the ability to irrigate at an effective rate of 5 millimeters (0.20 inches) per day or more. Returns could be optimized by reducing the irrigated area for corn for irrigation capacities less than 8 millimeters (0.31 inches) per day under average climatic conditions. Interestingly, reducing the area of the irrigated circle by turning off nozzles in the outer spans resulted in greater yields compared with omitting irrigation in sectors (or “pie slices”). Growing dryland cotton in the unirrigated outer rings further increased returns except under drought conditions. Greater application of irrigation water did not always generate additional income, which means that there is an opportunity for water conservation while maximizing profits.

Citation

Domínguez, A., Schwartz, R.C., Pardo, J.J., Guerrero, B., Bell, J.M., Colaizzi, P.D., and Baumhardt, R.L., 2022, Center pivot irrigation capacity effects on maize yield and profitability in the Texas High Plains: Agricultural Water Management, 261, 107335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2021.107335

Join Our Mailing List

Subscribe to Texas+Water and stay updated on the spectrum of Texas water issues including science, policy, and law.