With 38 public universities and 35 private colleges and universities in the state and many more across the country (and the world) interested in Texas, there’s a great deal of academic scholarship focused on water in the Lone Star State. In this column, I provide brief summaries to several recent academic publications on water in Texas.

Let’s start thinking about water!

Drying Up—Texas v. New Mexico shows that the Pecos River Compact is not equipped to handle climate change

Pecos River at Lewis Canyon. Credit: rockcanyon, stock.adobe.com

With the water struggles in the (other) Colorado River making the news, the impacts of climate change on the water-sharing agreements (compacts) have moved front and center. Maybe I’m a simpleton, but doesn’t proportional sharing address this issue? For example, if you and I agree to split each cookie that comes our way equally, you (and I) will each get half a cookie regardless of the size of the cookie. Of course, depending on our dieting status, we may not be happy with receiving a small cookie, but we’ll get our 50 percent each.

Scheuerman looks at the Pecos River Compact through the lens of climate change. He notes that the agreement allocates water to Texas proportional to the amount it received in 1947. This is Texas’ proportional part of the cookie. While a cookie is a cookie is a cookie, the size of the Pecos cookie is more difficult to discern, depending on the approach to the hydrology. In 2014, Texas asked New Mexico to hold back floodwaters resulting from Hurricane Odile. However, by holding 51,000 acre-feet of floodwaters for Texas, New Mexico warned Texas that Texas needed to account for the evaporative losses of holding that water, which amounted to 21,000 acre-feet by the time the water was released the next year. Texas disagreed, and the case went up the flagpole to the U.S. Supreme Court, where Texas lost.

Due to this case and other factors, Scheuerman argues that the compact needs to be proactive in considering what else may come with climate change and how to resolve disputes better. Based on the facts of the case presented in this paper, Texas was not being very neighborly in asking New Mexico to help with the flood but not accounting for evaporation. Texas may have felt that they were in the right based on the compact, but for a number of other reasons, it appears that they were in the wrong.

Citation

Scheuerman, N., 2022, Drying Up—Texas v. New Mexico shows that the Pecos River Compact is not equipped to handle climate change: Ecology Law Quarterly, v 49, n 2, https://www.ecologylawquarterly.org/print/drying-up-texas-v-new-mexico-shows-that-the-pecos-river-compact-is-not-equipped-to-handle-climate-change/

Impacts of climate change on water management

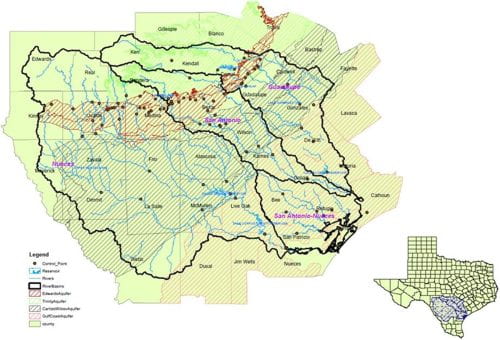

The general title of this paper hides that the work is focused on South-Central Texas and the Nueces, San Antonio, and Guadalupe river basins and the San Antonio-Nueces coastal basin with consideration of the associated aquifers. Fei and friends considered climate change and increased population-driven demands in their stochastic model. I could not follow what they did for groundwater (aquifer response functions, water tables [but not artesian pressures?], which aquifers?), leaving me with the impression that this is more of a screening model.

Results show that additional water-supply projects are needed in the region by 2050, with an additional 40,000 to 140,000 acre-feet needed for the San Antonio region and an additional 10,000 acre-feet for the Victoria-Corpus Christi area. However, the results are messy: by 2090, the volume of water needed with or without climate change will be about the same (and might be less for Victoria-Corpus Christi).

Research region (South Texas), river basins and aquifer

Citation

Fei, C.J., McCarl, B.A., Yang, Y., Ayana, E.K., Srinivasan, R., Lei, Y., Li, L., Sheng, B., and Fan, X., 2022, Impacts of climate change on water management: Applied economic perspectives and policy, v 44, n 3, p 1448–1464 DOI: 10.1002/aepp.13264

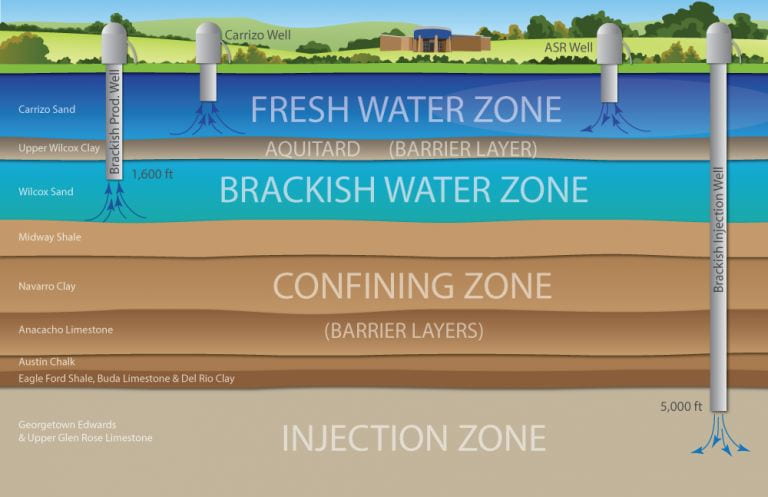

San Antonio Water System, Texas Carrizo Aquifer Storage Recovery Program

Geologic cross-section showing hydrogeologic units below the SAWS H2Oaks Facility.

San Antonio Water System’s aquifer storage and recovery project has been a rip-roaring success, storing close to 200,000 acre-feet of excess Edwards water into the Carrizo Aquifer in southern Bexar County to defer the impacts of drought on the city and benefit the endangered species in the Edwards Aquifer. Snyder and friends provide the definitive description of the design and operation of the project. The project has allowed San Antonio to maximize its Edwards permits while mitigating the effects of drought on aquifer levels, thus benefiting spring flows and endangered species at Comal and San Marcos springs and preserving downstream flows, which, in turn, benefit downstream species and users. In all, the project is expected to hold 233,000 acre-feet, although more may be possible. Finally, the authors note lessons learned for others to consider in their projects. Given the number of similar projects planned for the region, this paper will be a helpful reference.

Citation

Snyder, G.L., Pyne, R.D.G., Morrison, K., and Nixon, K., 2022, San Antonio Water System, Texas Carrizo Aquifer Storage Recovery Program: Ground Water, v 60, n 5, p 641–647, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35851955/

Join Our Mailing List

Subscribe to Texas+Water and stay updated on the spectrum of Texas water issues including science, policy, and law.